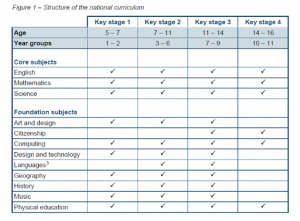

The current primary education system corresponds to a government implemented national curriculum that all schools have to follow (DfE, 2014). According to The Department of Education (2013), the national curriculum gives a synopsis of key knowledge that every student should be taught. The curriculum pre-determines subjects that are taught within schools and subjects vary depending on students’ age (DfE, 2013). The table below highlights the different subjects that each key stage is taught.

(DfE, 2013)

The current system is based on Hirsch’s theory of core knowledge (Hirsch, 1996). Hirsch (1996) believes that in order to allow universal participation all students should have a basic background knowledge in maths, English and science (Coughlan, 2013) which is demonstrated in the table above.

The current system supports aspects of social democracy, as every student is taught the same content (Seashore Louis, 2003). However, despite it supporting democracy to an extent, freedom and individuality are lost. This is because all pupils are undertaking the same predetermined subjects (Gov.uk, 2019). Teachers also work within a structured timetable to make sure they meet the fixed subject teaching hours (Nurmi and Kyngäs, 2007), once these timings have been met it usually leaves no extra time for free choice learning. This also contradicts the alternative education themes as there is no freedom for pupils to learn at a time that is best for them. Additionally, the current system does not support each child’s individual educational needs, as every child has the same amount of time allocated to them to spend on specific tasks.

In the primary education system, educational effectiveness data is obtained through standardised testing, which commonly occurs at the end of each key stage (Gov.uk, 2019). Data from national testing is collected and placed in a number of performance tables, allowing results from all over the country to be compared to the national expected results (Jones, 2010).

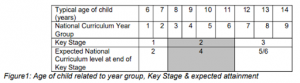

The table below shows the level a pupil should be achieving at a specific age. It shows that children are considered successful if they have reached a specific level at the right time. This infers that children are reduced to being viewed as numbers and are seen as underperforming if they have not reached the expected level. This corresponds to Carnie’s (2017) view, that schools are judged on what can be measured rather than the important aspect of learning and understanding that cannot always be assessed. Unlike the alternative, the current primary system focuses more on results and statistics, ignoring the child as a whole. Categorising individuals by numbers instead of displaying their individuality. On the other hand, if the system does not measure each student the same, there could be the risk of students being left behind, or missing something they are struggling with.

(DfE, 2012)

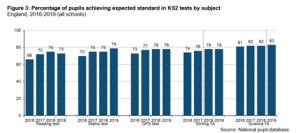

The core subjects, English, mathematics and science are monitored and compared at primary school. The overall results for each of the core subject areas become nationally averaged creating comparative results that are used by the government to assess the effectiveness of current educational standards (Jones, 2010). When examining the bar graph below, individuals may question the true effectiveness of our current test orientated education system (Jones, 2010). For a tested orientated system that is believed by the government to be effective (Wyse and Torrence, 2008), individuals may expect to see average result percentages to increase as time goes on. Despite this, when it comes to comparing yearly results as seen on the DfE (2019) graph below, the results contradict expected assumptions because they appear to be very similar, showing little to no progress in the four years. Furthermore, schools are focused on results. In year six, when students take their SATS, the fun is often taken out of learning due to the pressure they experience as anxiety levels increase (Claxton, 2008). This means that children are not enjoying school as they have a lot of pressure on them to do well This can come at the expense of children’s well being (Putwain et al, 2011). Therefore, it could be viewed as effective in terms of results, as a large percentage of children are reaching the expected level, but not effective in other areas such as the motivation that is needed to make learning fun (Wyse and Torrance, 2008).

(DfE, 2019)

The overall efficiency of the education system has to be measured to monitor the effectiveness of it. However, in primary education there could be an alternative way of assessing students development in a way that does not use as many formal standardised assessments (Jones, 2010). Within the current system, there is an assumption that results are important and that the higher the result, the more successful the school, as the government is constantly striving to drive up results (DfE, 2013 ;Jones, 2010 ; Claxton, 2008). Due to the school system being driven by performance, this has an impact on the stress of students’ (Claxton, 2008). The pressure of SATs in year six may become overwhelming for some and become a controlling factor in their lives taking vital time away from enjoying their childhood. This can lead to a lack of motivation due to them not having any choice in what they are being taught. Furthermore, each individual has their own strengths and weaknesses, and the current system is not enhancing what each pupil is good at, and not challenging weaknesses. Instead, the primary system reduces children down to three subjects that they are made to sit at the end of primary school (Carnie, 2017).

In spite of this, there are some positive aspects to it. The current system of testing in primary education allows all individuals to be working at a level playing field, as they all have to take part in the same mandatory examinations. The results gained from these examinations allow parents and teachers to gain a better understanding of the children’s development as it will highlight the child’s strengths and weaknesses in these key subject areas (Bew, 2011).

References:

Bew, L. (2011) Independent Review of Key Stage 2 testing, assessment and accountability [Internet]. Available https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/176180/Review-KS2-Testing_final-report.pdf [Accessed 9th March 2020].

Carnie, F. (2017) Alternative approaches to education: a guide for teachers and parents. 2nd ed. London, Routledge.

Claxton, G. (2008) What’s the point of school? Rediscovering the heart of education. Oxford, Oneworld.

Coughlan, S. (2013) Gove Set Out ‘Core Knowledge Curriculum Plans, BBC News [Internet]. 6th February. Available from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-21346812 [Accessed 5th March 2020].

Department for Education (2012) National Curriculum Assessments At Key Stage 2 In England , 2012 (Provisional). London, Press Office Department for Education.

Department for Education (2013) The national curriculum in England Key stages 1 and 2 framework document. Available from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/425601/PRIMARY_national_curriculum.pdf [Accessed 2nd March 2020].

Department for Education (2014) National Curriculum In England: Framework For Key Stages 1 to 4 [Internet]. Available from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-framework-for-key-stages-1-to-4/the-national-curriculum-in-england-framework-for-key-stages-1-to-4 [Accessed 5th March 2020].

Department for Education (2019) National curriculum assessments at key stage 2 in England, 2019 (revised) [Internet]. Available from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/851798/KS2_Revised_publication_text_2019_v3.pdf [Accessed 9th March 2020].

Gov.uk (2019) The National Curriculum [Internet]. Avaiable from https://www.gov.uk/national-curriculum/key-stage-1-and-2 [Accessed 5th March 2020].

Jones, H. (2010) National Curriculum tests and the teaching of thinking skills at primary schools – parallel or paradox? , Education 3- 13, 38(1), pp. 69-86.

Nurmi, K. and Kyngas, J. (2007) A framework for school timetabling problem. Proceedings of the 3rd multidisciplinary international scheduling conference: theory and applications, pp. 386-393.

Putwain, D.W., Connors, L., Woods, K. and Nicholson, L.J. (2012) Stress and anxiety surrounding forthcoming Standard Assessment Tests in English schoolchildren. Pastoral Care in Education, 30(4), pp. 289-302.

Seashore Louis, K. (2003) Democratic schools, democratic communities: Reflections in an international context. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 2(2), pp. 93-108.

Wyse, D. and Torrance, H. (2008) The development and consequences of national curriculum assessment for primary education in England. Educational research, 51 (2), pp. 213-228.