What are Pupil Referral Units?

Pupil Referral Units otherwise known as PRUs are centres out-of-school that have been designed to cater for a diverse set of students. These students include those who have a higher risk of being permanently excluded, have been permanently excluded, refuse to go to school, those who are pregnant or are without a place at a school as well as students being assessed in relation to Special educational needs (SEN) (Kinsella, Putwain and Kaye, 2019). PRUs are ran by the Local Authority, and it is their aim to help those students find suitable education whilst they are out of mainstream schools, however the main objective of PRUs is to get those students back into mainstream settings (Meo and Parker, 2004). PRUs were designed tackle the negative consequences that comes with being excluded from schools through respite and aim to reintegrate children back into mainstream schools in a way that makes the child feel as comfortable and confident as possible (Jalali and Morgan, 2018).

The Process of Exclusion.

There are two types of exclusion, the first being a fixed-term exclusion, in which the headteacher can temporarily remove a child from school. During this exclusion, during the first 5 days, students will be set work that will be marked, and it is the responsibility of the parent or guardian to ensure the student is not within a public place during the school hours (Baker et al, 2010). Children can also be permanently excluded from school, this means a child is expelled, however only the Head Teacher can exclude a child from a school, and it must be fair and legal, and parents should be told about the alternative education arrangement by either the school or the Local Authority (GOV.UK, 2022.e). According to the Government’s latest data from 2019-2020, there were 5,057 children who were permanently excluded, which is equivalent to 6 in every 10,000 pupils in the UK (GOV.UK, 2021). Children who face these sanctions, will most likely be sent to a PRU, and have been reported to have a lack of positive outcomes later in life (Hart, 2013).

The Curriculum and Teaching Within PRUs

Pupil Referral Units are an alternative way to education and have fewer teaching staff and more one-to-one teaching (Solomon and Rogers, 2001). However, whilst teachers in PRUs do not need QTS, they do need NQT, and have some work with children with SEN or EBD (Meo and Parker, 2004). They do not have to follow the national curriculum; however, there is an expectation to teach a broad and balanced curriculum in order to meet the pupils needs and enables them to be on par with mainstream pupils with it comes to educational attainment levels (Leather, 2009). Within KS4, maths and English should be taught, as well as science and ICT skills, students should be able to gain their GCSE unless their attainment prior to attending the PRU suggest otherwise, in that case functional skills or entry levels qualifications should be offered to the students (Ofsted, 2007). Students found the curriculums offered at PRUs engaging and relevant to them and valued the extracurricular activities offered (Michael and Frederickson, 2013). This means that more students found the curriculum had positive outcomes as the PRU catered for the young people’s needs and specifically taught them skills needed for their choice of career. Whilst others have a curriculum that included an emotional curriculum that was tailored specifically for their needs and therefore, they have positive behavioural and learning outcomes (Michael and Frederickson, 2013). PRUs have smaller class sizes which provides positive learning outcomes and students behaviour is more productive, class sizes can range from as little as four people and therefore the teacher has more time for one-to-one with students meaning self-progress is more likely (Michael and Frederickson, 2013).

The Pupils in PRUs

It is unsurprising that most pupils that attend PRUs have social, emotional and or behavioural difficulties (SEBD) as well as mental health issues, as they are more likely to have several risk factors in their lives (Hart, 2013). Fergus and Zimmerman (2005) cited by Hart (2013) discuss how there is an increased chance of negative outcomes due to the fact they have been exposed to risk, furthermore these factors naturally lie within the family or wider community and infrequently act alone. DfES (2004) cited by Harris, Vincent, Thomson and Toalster (2006) explain how some schools only idea to support students with behavioural issues is to exclude them, however this only disrupts their education and does not solve any of their underlying difficulties and can be even more damaging for them long-term. Students who find themselves unable to meet the demands of mainstream schools, and are excluded often feel shame, stigmatisation and therefore feel rejected from the school (Mainwaring and Hallam, 2010). Many of the young people attending PRUs have SEBD, and therefore struggle with social competence, which includes the child struggles with processing social information, adapting to different stations, and face friendship issues which all assists in the development of behavioural issues (Hukkelberg, Keles, Ogden and Hammerstrøm, 2019).

Outcomes for Pupils in PRUs

There are low standards and expectations when it comes to PRUS, and some have been labelled as ‘sin bins’ and storehouses that are used to dump unwanted pupils (Ogg and Kaill, 2010). Whilst PRUs offer GCSEs for the students at the provision, pupils achieve a limited number of qualifications at that level, as it has been shown that pupil’s educational achievement outside of mainstream schools is much lower than their peers (Pirrie and Macleod, 2009). This influences their future as statistics published for the years 2019/2020 show that only 62% of pupils in alternative provisions (including PRUs) went to a sustained destination after GCSEs compared to the 94% of pupils from mainstream schools (GOV.UK, 2022.c). A third of pupils (32.4%) in an alternative provision did not sustain their destination for the 6 months that is required, however pupils how went to an alternative provision were more likely to go into employment (GOV.UK, 2022.c). Tate and Greatbatch (2017) discussed how, due to the disruptions of education and the potential social, emotional, and mental health needs (SEMH) as well as SEN that some pupils at PURs have, they are more likely to become NEET (Not in Education, Employment or Training). In a study conducted by Tate and Greatbatch (2017), they found that a universal approach in alternative provisions were unproductive, and that students were disapproving of the way that labels are entrenched within mainstream schools, as they cease to forget and draw out issues that happened years ago, and therefore students are cautious of returning to mainstream education as they feel judged and unable to make a fresh start.

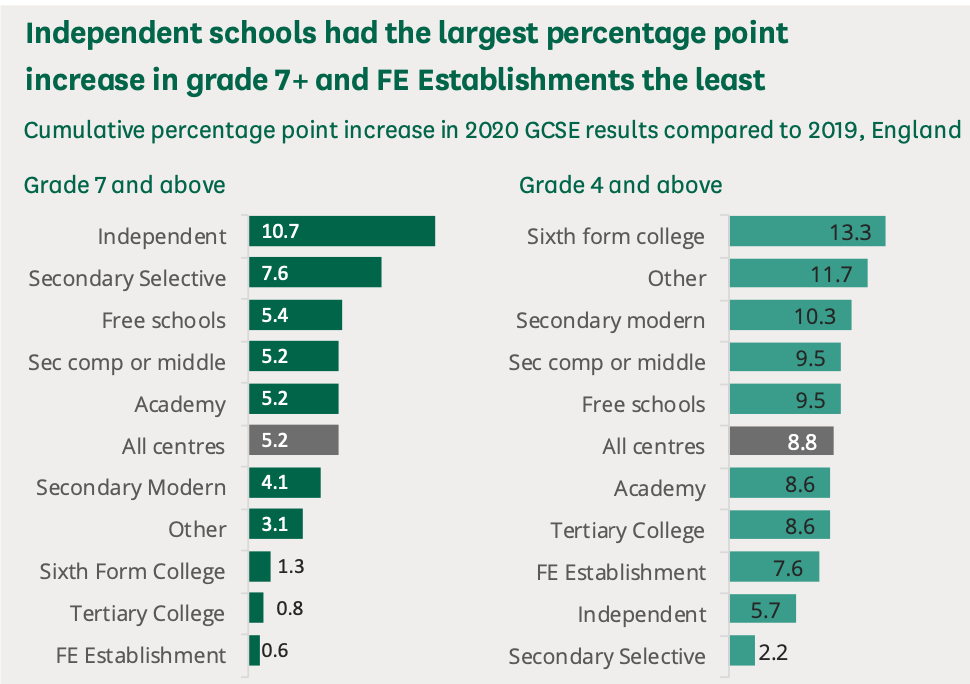

*Table shows students who achieved grade 7 and 4 in 2020 GCSE – PRUs and AP covered within ‘Other’

Reintegration into Mainstream Schools

Whilst the aim of PRUs is to reintegrate pupils back into full-time mainstream education, pupils have a weak understanding of what could happen to them if their return to full-time mainstream schooling does not work and consequently breaks down, however this is due to a lack of communication from the Local Authority or PRUs when addressing this issue (Hill, 1997). Since the introduction of PRUs, there was little collaboration between Further Education and PRUs. Due to this, there was indication from the government that there was a need for stronger collaboration between further education, PRUs, schools and employers to make sure that children who had been excluded from school were still given opportunities to succeed and break themselves away from social and educational exclusion (Culham, 2003). Due to this lack of communication, Secondary school students feel a lack of connectedness to mainstream schooling, which leads them to feel inadequate and label themselves as failures as they do not fit in to the school in comparison to their peers (Jalali and Morgan, 2018). Cooper and Stone (2000) cited by Jalali and Morgan (2018) explain how a lack of mainstream connectedness could account for the discrepancy students feel in understanding their behaviour, and therefore label themselves as misbehaved but blame the people around them for their actions, which therefore leads to resentment towards education.

Successful Reintegration into Mainstream Schools

Reintegration can be successful when PRUs, schools and Local Authorities work together, when early and informed planning takes place as well as involving the parent/carers and child in the reintegration process planning, giving the students a voice, and making sure they are heard. The Local Authority needs to make sure that the schools are inclusive, and it committed to responding and catering for the child’s needs, making sure support staff and services are available for the child if needed, for example a counselling service should the child feel they need it (Lawrence, 2011). This proves there should not be a one-fits all approach to reintegration, but several approaches and interventions in place based on inclusivity and making sure the children’s needs are met, as overall it is their future it is affecting, and making sure they reach their optimum ability is the most crucial factor (Lawrence, 2011).

Olivia Martin: 209007314