By Grace Wilson

Imprisonment of a parent involves the forcible separation of a parent and child from their ‘normal’ home environment. Whilst there is undeniable evidence on the impacts on prisoners’ children, it is important to consider the emotional and physical well-being of mothers and fathers in how they manage to be a parent ‘behind bars.’

Motherhood

High rates of pre-existing vulnerabilities such as domestic abuse, poverty, and mental health problems occur before going into prison. Over half of women in UK prisons have suffered domestic violence in their lifetime, whilst one in three have experienced sexual abuse. To continue, women in prison are five times more likely to have a mental health condition compared to the public. (Epstein 2012)

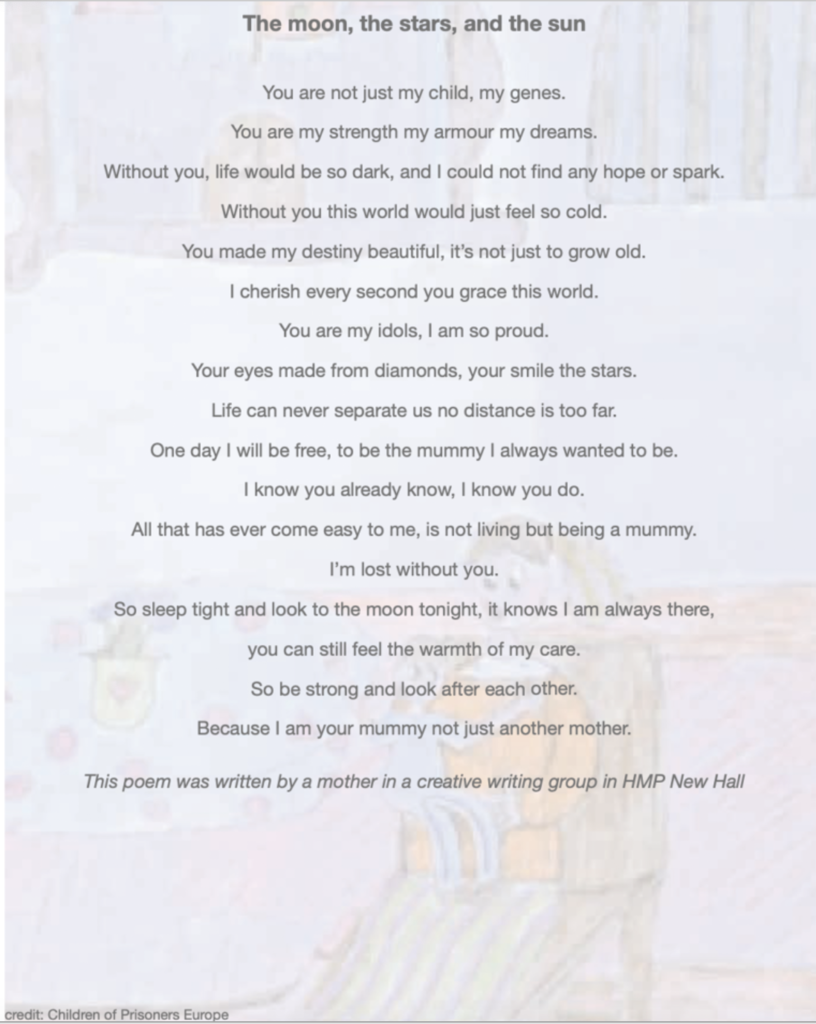

With this, in 2015, it was estimated that 66% of imprisoned women in the UK had children under 18, 40% being aged between 5-10 (PRT 2015). This suggests that many mothers deal with significant ‘mothering-related emotions’ as well as dealing with other issues. Baldwin (2018) comments on emotional wellbeing’s and that ‘mothers in prison not only bear their own pain and feel their own emotions but can also describe feeling the pain and emotions of their children. (Page 4) This highlights the need for a safe space for mothers who are struggling. ‘Stewart (2015) researched into mother support groups within prisons and quotes a prisoner describing how it felt to be with other mothers: ‘it means we can get together like normal mums who just want to spend time together and think about having a baby.’ (Cited in Baldwin, 2015:175)

Limited support and visitations are offered. In the UK, as there are only a small number of women’s prisons, many are no longer are in hometowns, or in proximity for family visits. The Prison Reform Trust (2015) found that the average distance from their family home was 60 miles. As a result, complications arise for children visiting and thus a barrier is automatically created for the mother. Baldwin (2018) comments on O’Malley’s (2013) research into highlighting the emotional damage mothers can experience during child visitations. O’Malley describes a ‘protective mechanism’ that some mothers create by not allowing their child to visit ‘suppress their own maternal needs to protect their children from the experience of visiting a prison. (Page 5)’

Women in prison are also subject to feeling like ‘bad mothers’ not only in prison, due to the lack of face-face contact, but also feeling ‘unqualified’ on release. Minson, Nadin, and Earle (2015) from The PRT explain that families experience financial problems, with 1/3 losing homes and possessions whilst incarcerated. The PFT (2015) also found that less than 1 in 10 women in 2012 had successful employment on release, meaning little financial support is provided to create a ‘child-safe environment.’

‘When I got out of prison I was in a catch-22… If your child doesn’t live with you, you can’t get accommodation, but you can’t get your child back unless you’ve got accommodation…. I wanted to do everything right. But eventually, I was just like, I want my son back.’

A woman interviewed by The Prison Reform Trust (2015) (Page 7)

Fatherhood

The emotional effects of being a father in prison, particularly in the UK, is not widely researched to the extent of the mothers’ emotions. This could be due to the social stigma of men expressing ‘emotions’ which is amplified by prison culture. Prison culture is inherently masculine, having to be always ‘hard’ and ‘strong’. Young (n.d) found that for many male prisoners, they are required to put on a ‘presentation of self’ around other male prisoners that promote ‘normal masculine behaviours.’ Jewkes (2005) found in her study that men use these ‘masculine behaviours’ as a mask ‘for coping with the strains of imprisonment (page 53).’ Looking at the communication between a father and child, a father may be more inclined to hide certain emotions and act differently in front of their child and then return to the social expectations inside prison. Young (n.d) described these adaptations as ‘stress-inducing as the boundaries between identities become blurred (page 22.)’ This stress can change their perceptions of themselves as no longer being a ‘good father.’

For fathers who experience this blurred identity, it is important for them to try maintaining relationships with their children. However, because of the lack of visitations available and ‘blurred’ perceptions of themselves, fathers often feel embarrassed and shameful of being away from their children. This can lead to fathers no longer wanting to see their children. For some men, they can start to create ‘idealisations’ of the child, due to the lack of visitations. Bourgeba (2002) found that in a French prison ‘the more the father misses the child, the more he invests in the child and imagines him/her in an idealised form.’ Bourgeba (2002) also found that some ‘fathers actually deny that their child has grown.’ They speak as if their child is still as young or undeveloped as when they left to go into prison. This phycological need for their child will only add to the stress and complications surrounding prison life.

Few charities are available which help support fathers in prison. One in particular, ‘Safe Ground’ run programmes such as ‘Fathers Inside’ which help fathers focus on ‘parental responsibilities and children’s education, development and wellbeing’ (Safe Ground) in an intense 5-week parenting programme. These programmes developed by Safe Ground have been proven to reduce reoffending rates by 40% (Justice Data Lab 2016) and has highlighted the need for support for fathers who struggle with maintaining relationships with their families.

“I have a better understanding of child development, how to be a better role model and how not to be a selfish person in life.”

A Father’s opinion: ‘Father Inside’ (2007) safeground.)

To conclude, both mothers and fathers battle with the identity of being ‘good’ parents whilst separated from their children. Further support should be provided for the prisoners who are struggling inside, as well as helping to adjust to life after incarceration.

Bibliography

(AN) (n.d) Fathers need Families: Imprisoned Fathers. London [Online PDF Available at https://fnf.org.uk/phocadownload/research-and-publications/factsheets-and-guides/imprisoned_fathers.pdf] (Accessed 17th November 2021.)

(AN) Safe Ground Charity (n.d) Fathers Inside [Online Available at: http://www.safeground.org.uk/prisons/fathers-inside/ ] ( Website Accessed 20th November 2021)

Baldwin. L (2017) Motherhood disrupted: Reflections of post-prison mothers, De Monefort University [Online Available at: https://www.nicco.org.uk/userfiles/downloads/5ac5cb4b3301e-motherhood-disrupted.pdf ](Article accessed 17th November 2021)

Beresford.S (2018) What about me? The Impact on children when mothers are involved in the criminal justice system. [Online Available at: http://www.prisonreformtrust.org.uk/portals/0/documents/what%20about%20me.pdf ] (Accessed 20th November 2021)

Dr Bouregba. A (2002) Speech on the “Imprisonment: Family Ties and Emotional Issues” France. [Online Available at https://childrenofprisoners.eu/the-issues/fathers-in-prison/] (Accessed 10th November 2021)

Epstein, R. (2012) Mothers in Prison: The sentencing of mothers and the rights of the child. Coventry Law Journal. Coventry Law School.

Jewkes. Y. (2005) Men Behind Bars: “Doing” Masculinity as an Adaptation to Imprisonment, Men and Masculinities, 8 (1) Hull. Sage Publications. [Online Available at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1097184X03257452 ] (Accessed 27th November 2021)

Ministry of Justice (2016) Justice Data Lab analysis: Re-offending behaviour after participation in Safe Ground’s Father Inside Programme. [Online Available at: http://www.safeground.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Data-Lab-Report.pdf] (Accessed 20th November 2021)

Minson.S, Nadin. R and Earle. J (2015) Prison Reform Trust: Sentencing of mothers: Improving the sentencing process and outcomes for women with dependent children. A discussion Paper.The University of Oxford. [Online Available at: http://www.prisonreformtrust.org.uk/Portals/0/Documents/sentencing_mothers.pdf]

O’Malley.S (2013) The Experience of Imprisonment for Incarcerated Mothers and Their Children in Ireland. (Unpublished MA Thesis)

Young. E (n.d) The Experience of fatherhood post-imprisonment. John Sunley Prize Winner Masters Dissertation. [Online Available at: https://howardleague.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/The-experience-of-fatherhood-post-imprisonment.pdf] (Accessed 20th November 2021)