by Jayne Stead

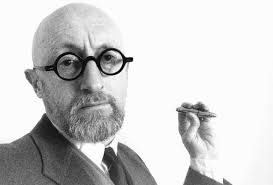

Nicholas Royle is a busy man. He is Senior Lecturer in Creative Writing in the Manchester Writing School at Manchester Metropolitan University and has been Chair of Judges for the Manchester Fiction Prize since it was launched in 2009. He is also an author of many novels and short story collections. As an editor he has worked on novels and anthologies of short stories. Royle owns and manages Nightjar Press, which publishes short stories as signed, limited edition, chapbooks. Like I said – a very busy man!

He responded to our request for an interview with enthusiasm and his answers to our questions are thoughtful, comprehensive and authentic. I cannot thank him enough for taking the time to add to our growing bank of publishers featured on the blog.

He has interesting things to say on where presses are located and a refreshing take on his relationship with authors but not necessarily agents! As a frequent customer of his ever growing chapbook collection I can recommend them wholeheartedly – great, affordable and beautifully produced short reads!

Here’s what he had to say about being one of our innovative and passionate publishers:

Who are you and what is your current job at the press?

I am Nicholas Royle. I founded Nightjar Press in 2009. I am the editor and publisher.

How did you get into publishing? Do you think a degree that studies publishing creates more interest in the industry? Is it a good leveller?

I started my previous small press, Egerton Press, in 1991, in order to publish an anthology, Darklands, which was followed a year later by Darklands 2. In 1994 I published Joel Lane’s short story collection The Earth Wire and then wound the press up. Towards the end of 1994 I started working for Time Out. I was mainly an editor on the City Guides series, but also devising and editing short story anthologies. I do think that a degree in publishing is likely to create more interest in the industry. Is it a good leveller? I don’t know. It has the potential to be. Maybe, historically, publishing has the reputation of being the kind of business in which it’s useful to know someone if you want to get into it. (I didn’t know anyone when I got into it.) Now that it’s possible to study publishing and gain a qualification, it should, theoretically, be easier to enter the industry.

What are you currently working on?

At Nightjar we’ve just published ten new titles. We publish individual original short stories in chapbook form and we’ve never done ten at the same time before. So at the moment I’m mostly stuffing envelopes and walking to the post box. But also thinking about the spring and wondering how I can tackle the long list of titles waiting to be published without repeating the mistake of publishing too many at the same time.

Do you have a mission statement? How does your press encapsulate your values?

There’s no mission statement as such. I suppose the press encapsulates my values relating to publishing by setting very high standards – for the work itself, cover art, design, editing, dealing with authors, responding to writers submitting work, getting orders out to readers – and always trying to meet them.

Where do you stand between tradition and innovation? How does the press represent this?

I wouldn’t be interested in digital publishing, but I do make use of digital printing. I’m wedded to print. Chapbooks go back to the sixteenth century, but I don’t think they had full-colour photographic covers like ours do. I’m very interested in uncanny/gothic literature and in experimental fiction and, increasingly, in what might happen when these overlap.

How easy is it to start your own press – and how do you measure success?

It’s very easy to start your own press and operate at a certain level, but, if you want to produce and sell professional-standard publications, it requires a lot of work (and expense). I wouldn’t be able to do what I do without the help of an old friend and former colleague, John Oakey, who takes care of the design, and without the help of my daughter, Bella, who maintains the website (originally designed and maintained by Claire Dean). I measure success in terms of happy writers and readers. If people respond with enthusiasm to what we publish, and if writers enjoy the experience of being published by us, then I suppose that’s success, but to be honest it’s not a word or a concept that I think about a great deal.

What is your submissions policy? How does future success change this?

I’m not a big fan of submission windows; our door is always open. I don’t put guidelines on the website. Instead there’s a slightly passive-aggressive line about how we welcome submissions from writers who have taken the trouble to research what we like. In other words, who have ordered a few titles. I get a bit tired of people who write saying they think their 12,000-word historical fantasy would be a perfect fit for Nightjar, or whatever. How they come to that point of view is a mystery to me. As for the future, who knows what will happen?

What is a successful submission to you?

I like it when a writer orders a few titles and allows some time to pass, during which I imagine them reading the stories and having a good long think about whether their work might fit in, before submitting something. This may not guarantee acceptance, but it’s a good start.

Do you actively go looking for work through outreach work/commissions etc?

Not commissions, but I do sound people out. I do sometimes invite submissions from writers I admire who I think might be a good fit, but I’m open-minded about all submissions (except the 12,000-word historical fantasies).

How do you decide on themes for submissions? Do you try and look for a gap in the market? Is it down to personal interest? Committee? How much trust do you put in agents and how much do you encourage them?

There are no themes for submissions. We publish stories that tend to be either dark, strange, uncanny, gothic, weird or macabre and, perhaps, experimental. I’m not interested in ‘the market’. Nightjar is not a money-making enterprise. It’s more of a black hole into which I throw £££££££. What we publish is entirely down to personal interest. There is no committee.

As for agents, they are like anyone or anything else; there are good ones and bad ones, benevolent ones and annoying ones. I get almost no approaches from agents and never approach potential authors through their agents. I pay £50 for a story. Show me an agent who wants to earn £5. I check with a writer that a story is previously unpublished, but all rights remain with authors. I’m happy if an author, or their editor, acknowledges a story’s first appearance as a Nightjar publication when it’s later reprinted in their collection or in an anthology (and I’m not if they don’t, eg when Penguin acknowledged Leone Ross’s collection rather than Nightjar Press when they included ‘The Woman Who Lived in a Restaurant’ in The Penguin Book of the Contemporary British Short Story edited by Philip Hensher. The story was first published as a Nightjar chapbook before reappearing in Leone’s collection Come Let Us Sing Anyway). Very occasionally you approach an author and you agree to work together and, it seems, there’s mutual trust, and then their agent gets involved and everything takes longer and is more complicated and involves a lot of faff and is, as a result, much less enjoyable.

How would you define your editorial process? Collaborative? Specific?

The editorial process is collaborative and depends entirely on what needs doing. I don’t change anything without checking it with the author. Sometimes virtually nothing needs doing; other times there’s a lot of back and forth, and that’s fine, it’s normal. I am very fussy, extremely picky. Things have to be right. I can count on one hand the typos there have been in Nightjar publications since we started and still have a couple of fingers remaining.

What is the author’s role in your particular publishing process? How much involvement do they have?

The amount of author involvement in the publishing process depends on the author. If they are up for helping to promote the publication among family and friends, or among a wider network of readers and fans, that is always welcome. I enjoy the stage of the process where orders start coming in from names I don’t know, people associated with a particular author, who will order a single copy of their title and nothing else with it and I sense I’ll never hear from them again unless I publish that author another time.

All our stories are published in pairs. Each story is published as an individual chapbook, but alongside another story, usually by another author, that speaks to it or resonates with it (the cover art is chosen, or created, to reflect this). I love it when readers order pairs of stories, but if they’re only interested in supporting their friend or favourite author, that’s fine, too. If an author is on social media, then I definitely welcome them getting involved in the promotion of the title on whatever platform.

Is the publishing industry getting a metaphorical kick up the backside from the Northern presses?

Maybe. I don’t really know. I might say yes and then the next day someone starts a brilliant independent press based in Penzance or Chelmsford, or, for that matter, London. Look at Influx Press, based in London. I love Influx Press. I love that they are reissuing almost the entire back catalogue of Joel Lane, previously published by Egerton Press and Nightjar.

How important is it that Nightjar remains as a press based in the North – how does location help anchor the press? If at all?

I don’t think it does. Look at Salt, a lively, ambitious, successful small independent (for whom I worked for several years as an editor acquiring novels and short story collections and for whom I still edit the Best British Short Stories series – plus, they published my latest book, White Spines: Confessions of a Book Collector). They’ve moved around from Cambridge to London to Cromer. It doesn’t alter their identity. I spend some of my time in London. Nightjar could be based in London. It wouldn’t make any difference. It would still be operating out of a bedroom.

Do you need a social media presence as a writer? Does it help? Does it count against you if you don’t have one?

I think it helps a lot. I’m always pleased if a Nightjar author has a (positive) social media presence, but it doesn’t come into it at all when considering a submission.

What are your ambitions for the press in the future? Do you see yourself expanding? More of the same? Into other forms? Non-Fiction/Poetry/novels/short fiction?

We have already done one side project, a mini-anthology of short stories on the theme of invisibility called The Invisible Collection. It stuck very closely to the theme, managing to be practically invisible. We have no plans for another anthology, but there is a plan for another project. I don’t know when that will happen.

If you were to recommend one chapbook from your back catalogue for us to read today which would it be?

I’d rather not pick out one title from those that are still in print, so I’ll go for Leone Ross’s ‘The Woman Who Lived in a Restaurant’, which Nightjar published in 2015. Buy Leone’s collection, Come Let Us Sing Anyway Come Let Us Sing Anyway (Peepal Tree Press), or read the story online at the Barcelona Review