YSJ Geography’s Black History Month celebrations: A summary, and looking ahead

Geography at York St. John University celebrated the 2021 Black History Month with blog posts every weekday. In the first week, we highlighted the achievements of Black environmentalists who have contributed to how we look after our planet. In the second week, the posts celebrated the month through five landscapes – rural and urban – bringing them visibility and highlighting how they contribute to society. Week 3 drew attention to people, places, and documents that could be easily overlooked when celebrating British black history. The blog posts in the final week highlighted the contributions of some black scholars to the field of Geography.

Wangari Maatthi. Credit: Oregon State University

Overall, we wanted to not only recognise black people, but highlight the complexity and celebrate the breadth and depth of Black culture and history while highlighting how they have and are contributing to Geography, society and the environment. It is also about raising awareness of the contribution of Black people to our subject, culture and society. Through these posts, we are able to articulate some of the areas Black History is integrated and plays a prominent role in our research and teaching in Geography at YSJ. Black History Month only happens once a year, but for us we work to integrate it into our teaching all year round.

Wangari Mathai and George Washington Carver are two names that feature on our Sustainability: Global Environmental Challenges module (led by Olalekan Adekola) when looking at building our understanding of the history of environmental movements. In this module, there is a case study on the Niger Delta wetlands and the activism of Ken-Saro Wiwa as part of our discussion on the complexity of managing resource-rich globally significant ecosystems. Students will also come across some of the writings of Robert Bullard when we discuss Environmental Justice especially in discussing Consumption and Waste (specifically the problems associated with electronic waste in the Global South).

The blogs in Week 2 are relevant to some of our staff research and modules we teach at YSJ. For example, Joseph Bailey research how cultural heritage, geodiversity, and biodiversity interact to shape ecosystems. These are important concepts that are discussed in the Year 1, Ecosystem and Biogeography module, and Year 3, Habitat management module. Discussions around sacred forests and animals feature prominently on our Nature/Culture module. For example, we discuss their values and how they can challenge representations that separate humans and nature. Our blog also features a post on rivers and Yoruba people in Nigeria.

Looking over Tanguieta. Rudi Verspoor, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0.

Discussions around how processes such as gentrification have erased spaces for minority groups such as Blacks and LGBTQ would be a topic on our Urban Geography and Cities in Transition modules – these are areas of research interest to Su Fitzpatrick and Jude Parks. We have discussed urban landscapes in our blog. The week 2 posts also emphasise areas we work on such as giving communities voices in the management of landscapes (we discuss the scared landscape of Tigray in our blog) and the question of synergy between traditional belief systems and development pressures.

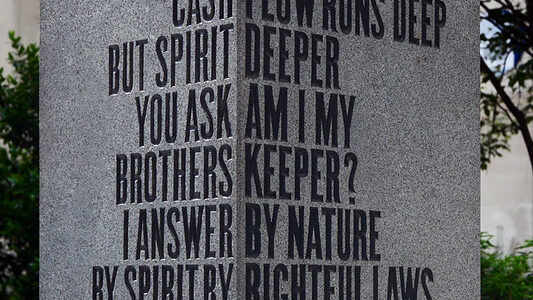

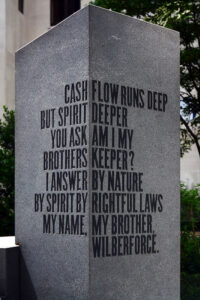

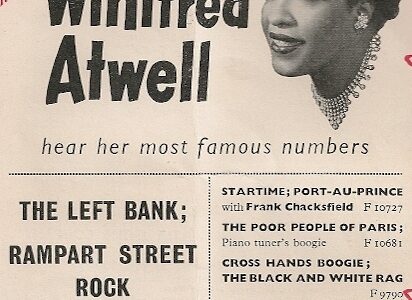

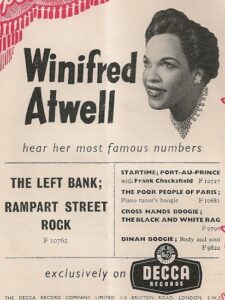

The blog posts in week 3 are relevant to modules where we explore ideas, political power, and empire in Britain. For example, in our Fieldwork module, we consider the role of empire in Geography. This could include highlighting the contributions and roles played by former slaves such as Ignatius Sancho as well as slave owners mentioned in our post on Glasgow streets. And don’t miss our posts on Freetown, Black musicians, and the Slave Compensation Act 1837.

The works of black scholars we celebrated in week 4 feature on a variety of our modules. The contributions of Akin Mabogunje to the discipline are discussed in our Year 1 Fieldwork Studies module. The year 2 Geographical Thought module incorporates the work of black scholars such as Stuart McPhail Hall, Milton Almeida dos Santos, and Katherine McKittrick. This module examines how knowledge is created within Geography, and so considers the nature of the discipline. As staff teaching Geography at university, questions of what Geography is, what it does, how, and why – questions addressed by scholars such as Richard Tabulawa – are central to our practice now and into the future.

Glasgow streetnames, showing Buchanan Street & Nelson Mandela Place. Credit Steven Collis. Attribution-NonCommerical-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0). https://www.flickr.com/photos/stevencollis/47615014732/