Education is only mandatory in England from the ages of five to sixteen years of age (“The UK Education”, 2020). Between these year’s education facilities will follow the national curriculum or in the case of Free Schools and Academies ‘offer a broad and balanced curriculum that covers English, maths, sciences and RE’ (Roberts, 2019). The Early Years Sector, follow the Early Years Foundation Stage Statutory Framework (EYFS), for ages nought to five years of age. This sector covers three prime areas; PSED (Personal, Social and Educational Development), Communication and Language and Physical Development (Department for Education, 2017). Section 78 of the 2002 Act requires the curriculum at maintained schools to be “balanced and broadly based” (Roberts, 2019) and to: promote the spiritual, moral, cultural, mental and physical development of pupils at the school and of society; and prepare pupils at the school for the opportunities, responsibilities and experiences of later life. (Roberts, 2019)

Schools are required to be open to students for a minimum of 190 days a year (“Primary Education”, 2019). The school year is broken down into three terms: fall, spring, and summer. Each of these terms are divided into two half-terms, separated by half-term holidays. In the summer, there is a long break between July and August that is usually about six weeks long (“Primary Education”, 2019). There are also two or three-week breaks at both Christmas and Easter.

Schools are not required to dedicate a certain amount of time to any one subject, however, they are required to provide sufficient instruction for all areas of the curriculum (“Primary Education”, 2019). An average school day generally starts around 9:00 a.m. and ends around 3:30 p.m. with a one-hour lunch break in the middle. Schools can also provide optional extra-curricular activities outside of school times.

The National Curriculum

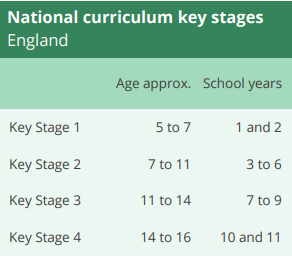

In 1998 the National Curriculum was created as a framework for learning. This ensured standardized learning across the country, so everybody learned the same materials. ‘Maintained schools in England must teach the national curriculum to pupils aged approximately 5 to 16 years old’ (Roberts, 2019). The National Curriculum is divided into four stages;

(Roberts, 2019)

(Roberts, 2019)

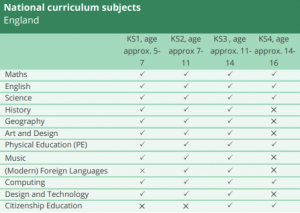

The following table shows the subjects included in the national curriculum at primary and secondary level, these subjects were set out in Sections 84 and 85 of the Education Act 2002 (Roberts, 2019).

(Roberts, 2019)

(Roberts, 2019)

Early Years

The EYFS provides a ‘long-awaited and distinctive educational phase’ (Rogers, 2011). Providing a play-based and developmentally appropriate curriculum which merges the concepts of education and care (Roberts-Holmes, 2012). The EYFS include seven areas of learning and development set out by the Department for Education (2017), three ‘prime’ areas as seen in the introduction and four ‘specific’ areas:

-

literacy

-

maths

-

understanding the world

-

expressive arts and design.

The Early Years from ages nought to five are broken down into:

-

From ages nought to two years, the play and development is mostly parent led, with some input from social or education support workers. The parents may attend group sessions, which are led by educational professionals. Parents are given support from pregnancy onwards by professionals.

-

From two to three years some parents will be offered childcare support of 15 hours term time in a nursery or child minder setting with the 2-year funding available. This will be funded by the government and given to families in need or children who may need additional support.

-

Ages three to four is Foundation Stage 1, where the children can attend a Nursery setting for up to 30 hours a week payed for by the government with 3-year funding. This is offered to all parents regardless of background or income.

-

Ages four to five is Foundation Stage 2, where children will attend Reception. This usually takes place in a school setting.

The Early Years sector is varied in the settings and environments that it provides. Early Years settings may include; child minders, day nurseries, pre-schools, and holiday play schemes. All of these settings must follow the EYFS framework and policies. Throughout the early year’s settings children are tested through observations to track their progress when moving into Key Stage 1. Their progress is tracked alongside the early learning goals, children are judged to be either ‘emerging’, ‘expected’ or ‘exceeding’ (Tower Hamlets, 2019).

A key agenda linked to the early years is Every Child Matters agenda, set out in 2003. This agenda sets out ways in which to ensure that every child is safe, healthy, and enjoying and achieving with their school and home life. This agenda was set out to ensure that no harm or negligence is shown towards a child. As the Early Years sector has many different departments working together towards a common goal it ensures that every department plays their part in keeping each child safe and happy (Chief Secretary, 2003).

When discussing the effectiveness of the EYFS it is important to understand that at this age children will not be tested and easily tracked, as between the ages of nought to five children are constantly changing and growing. When assessing effectiveness in the early years, you can assess whether it prepares children for future education, life and individual development. What children experience in their early years provides the essential foundations for ‘both healthy development and their achievement through school’ (Tickell, 2011). The early years settings are essential in ensuring that every child is reaching their full potential as ‘a strong start in the early years increases the probability of positive outcomes in later life; a weak foundation significantly increases the risk of later difficulties’ (Tickell, 2011).

One way to assess its overall effectiveness is through assessing the teachers and the input they have on the child’s life. Effective teaching and learning are key ways in which the early years sector can ensure that every individual child is given the same chance to thrive and develop as each other. In planning and guiding children’s activities, practitioners must reflect on the different ways that children learn and reflect these in their practice. Practitioners must ensure that children are; ‘playing and exploring’, are involved in ‘active learning’ (Tickell, 2011), and that children are thinking critically about the world, this may be through creative arts or building. By the practitioner ensuring that all these criteria are fulfilled, it means that each child will have the best chance to thrive and develop in the early year’s stages.

One way which the early years sector ensures all criteria is being met by both child and practitioner is through assessing regularly. There is ongoing assessment’s where the children are observed by practitioners, this will be logged and tracked and the practitioners will then ‘shape learning experiences for each child reflecting those observations’ (Department for Education, 2017). There is a formal assessment with a progress checks at aged two. This progress check must identify the child’s strengths, and areas where the progress is ‘less than expected’ (Department for Education, 2017). Once a child reaches five there will be an Early Years Foundation Stage Profile produced by the practitioners working with each individual child. This profile will provide; parents and carers, practitioners, and teachers with ‘a well-rounded picture of a child’s knowledge, understanding and abilities’ (Department for Education, 2017) before moving into Key Stage 1. By the practitioners ensuring that they are delivering effective teaching methods and providing the best support and care for parent and child, it ensures that strong foundations are built for a child when moving on to the primary education phase.

Primary Education

Primary education consists of Key Stages one and two (“UK Education”, n.d.). During primary education, there are three main national assessments that students must take due to the Education Act of 2002: the Year 1 phonics screening check, the end of Key Stage one assessment, and the end of Key Stage two assessment (“Primary Education”, 2019). The first mandatory assessment is the phonics screening check that was introduced in 2012 (“Primary Education”, 2019). This is taken by every child at the end of year one, usually in June. This assessment checks how well students recognize and understand English sounds, how these sounds correspond to the alphabet, and how the sounds interact to form words. The test is produced by the Standards and Testing Agency (STA), but is administered and marked by the student’s teacher. The teacher then submits the results to the Department of Education. This check helps teachers identify students that may need extra help learning reading skills (“Primary Education”, 2019).

The end of Key Stage 1 assessment takes place at the end of year two when students are between the ages of six and seven (“UK Education”, n.d.). This assessment is done through teacher assessments. Teachers assess each student’s skills in reading, writing, mathematics, and science. There are multiple things that help a teacher make their assessment judgements: teachers assess students throughout the year while teaching, a framework to help teachers make accurate decisions, local authorities that can help ensure judgements are accurate, and the national curriculum tests administered in May (“Primary Education”, 2019). These national curriculum tests are set by the STA and marked by teachers. The assessment consists of two mandatory tests in reading, one in arithmetic, one in reasoning, and an optional test in spelling, punctuation and grammar. Teachers report their end of Key Stage one teacher assessment judgements to local authorities, who then submit the results to the Department for Education (DfE).

The end of Key Stage 2 assessment takes place after year six, when students are ten to eleven years of age (“UK Education”, n.d.). This assessment is different from the one taken after Key Stage one. It includes a teacher assessment judgement and an external assessment (“Primary Education”, 2019). The teacher assessment judgement is similar in manner to the one after the completion of Key Stage one. The national curriculum tests in English and mathematics take place in May (“Primary Education”, 2019). These are again set by the STA, but administered by the teachers. The tests include: two in grammar, punctuation and spelling, one in reading, one in arithmetic, and two in reasoning. The scores on these exams do not affect acceptance to secondary school. They are used to show which students might benefit from additional support in certain areas (“Primary Education”, 2019).

Parents annually receive written reports around July. This must cover the child’s achievement, progress, attendance, result of teacher assessments (if they just finished Key Stage one or two), and how parents can arrange to discuss the report with a teacher at the school (“Primary Education”, 2019).

There are many different views about whether or not this testing method is the best way to see if the current education system is effective. On one hand, these tests are a way to see what each student has or has not learned. This is the way schools have been assessing learning for ages. However, tests do not look at the child as a whole. There are many other things that are important to learn in school that cannot be assessed on a written exam: the ability to share, motivation, work ethic, etc.. Some children also get very nervous for tests and may not perform to the best of their abilities. Therefore, an exam would not show their true potential. The UK has made improvements in this aspect. There are now teacher assessment judgements, which have been shown to be as reliable as standardized tests (Rimfeld et al., 2019). These teacher assessments allow part of the Key stage assessment to be influenced by the teacher who has worked with them the entire year. This takes some of the pressure and stress regarding the tests off of the students. Some studies are even suggesting increasing the weight of the teacher assessments and decreasing the weight of the standardized testing (Rimfeld et al., 2019). This would limit the financial cost of testing and decrease the emotional burden placed on the student. There are many opinions on whether or not the UK’s educational system is effective, but it all comes back to the National Curriculum and testing.

Secondary Education

The secondary school system in England is for students ages 11 to 16, leading on from a primary education. It involves the key stages three and four which lead up to the General Certificate of Secondary education (GCSE) exams. This system has been updated in recent years with changes to the exam system and types of schools. Currently there are multiple types of public schools to choose from, these include grammar schools, academies, free schools and state managed schools. These school types all have slightly different government set rules which they must follow.

Free schools and academies are funded by the state but are independent of the local authority meaning they are not required to follow the national curriculum however there is guidance that they must teach a ‘broad and balanced curriculum’ (Gov.uk, 2020). The difference between these schools tends to be that free schools are completely new schools set up by various groups including charities and businesses (Danechi and Roberts, 2019).

Grammar and other state managed schools must follow the national curriculum unlike the other school types. This curriculum details which subjects must be taught and outlines the content of these. When students get to KS4 they have the opportunity to choose which subjects they would like to continue studying. The chosen subjects are those the student will take the GCSE exams for.

The main distinction of grammar schools is that students take the 11 plus entry test to obtain the opportunity to study there, while other school types are not permitted to do this. This entry test varies for each school, but usually includes maths, English, verbal and non-verbal reasoning. Prospective students must achieve a certain mark in these tests to be accepted, therefore grammar school students tend to achieve higher grades in GCSEs compared to other schools.

After completing GCSEs, students have multiple options of continuing their studies. One of the main options is Advanced Levels (A Levels), which involves studying three or four subjects for two years, then taking the required exams for each subject. Another option is BTEC qualifications which are practical based focusing on an individual subject, for example business. Instead of exams at the end of the course, students submit coursework throughout the year for individual topics within the subject. Apprenticeships are another option which are ideal for young people wanting to go straight into work at 16. These students will work full time alongside experienced staff to obtain training in the field while also attending lessons at college for off the job training (National Apprenticeship Service, 2019).

When deciding whether the current secondary education system is effective, it is important to examine what makes a successful school, while also taking into account that effectiveness is a contested term, meaning there are different viewpoints on this topic (Ko et al, (Department for Education, 2013)2014). In one report the characteristics of the most efficient schools were listed (Department for Education, 2013). These included high quality teachers, financial management of a high standard and accountability.

The report goes on to show teacher quality as being the most important variable in a school’s success, as having a good teacher for two years is estimated to be worth three grades on average for students who are taking nine GCSEs when compared to students who have an average teacher. A school’s overall grades are a factor of how successful it, higher grades show students are performing well, reflecting well on the school. Other variables of school success involve producing students who are well prepared for the future, which goes beyond simply rates of students going into higher education. It can also include employability and life skills. In addition to this, students who are encouraged to engage with the learning and enjoy their work tend to do better. The system currently could not be said to be effective as these characteristics have not been met.

League tables detail how well the pupils of each school do in their GCSE exams, so they are used to gauge the school’s effectiveness. Therefore, parents find these tables useful for deciding where to send their child. Publishing these results creates competitions between schools which in turn drives up standards (BBC News, 2019). Schools which are higher on the tables will have more applicants, and therefore more students than those lower down, meaning they have more funding available. This funding formula therefore makes the assumption that larger schools are higher quality. These tables may be seen as effective as they keep schools accountable, but instead they emphasise the perceived importance of testing.

Through league tables only showing grades, it shows schools main aim is for students to do well in exams. According to Ofsted (2019), students tend to be taught only what is in the exam specification, which is essentially teaching to the test. This only gives students a shallow understanding of the topics rather than a broader in-depth knowledge of each subject area. Through limiting the content taught in each topic it doesn’t allow for students to learn properly and explore their interests, especially when it comes to GCSE exams where many students resort to cramming facts, which they will shortly forget ( Leithwood et al, 2006).

Schools also do not provide adequate teaching of employability skill, which are “paramount when it comes to making young people employable” (Kashefpakdel et al, 2018 p. 1). Important employability skills include problem solving, teamwork and communication. Many teachers believe these skills are incorporated into their lessons, however this number was much lower when teachers were asked about assessment. This was evident especially with areas such as teamwork and creativity.

The Programme for international student assessment (PISA) is another form of testing taken by some 15 and 16-year-old students, which involves reading, maths, science and global competence. PISA tests are different to GCSE exams as they address competence in real life challenge instead of assessing the ability to memorise facts (OECD, 2018). Currently the United Kingdom is placed 10thon average, which has only fluctuated slightly in recent years. This calls into question whether all the changes that have been made to the education system have been successful. These scores could show that the education system does prepare systems for real life challenges, which the test is centred upon.

References

https://www.gov.uk/national-curriculum/key-stage-1-and-2

Chief Secretary, 2003. Every Child Matters, London: Government.

Department for Education, 2017. Statutory framework for the early years foundation stage, s.l.: Government.

Primary Education (2019, September 11). EACEA. Retrieved on May 2, 2020, from https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/primary-education-49_en

Rimfeld, K., Malanchini, M., Hannigan, L. J., Dale, P. S., Allen, R., Hart, S. A., & Plomin, R. (2019). Teacher assessments during compulsory education are as reliable, stable and heritable as standardized test scores. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(12), 1278-1288.

Roberts-Holmes, G., 2012. ‘It’s the bread and butter of our practice’: expereinecing the Early Years Foundation Stage. International Journal of Early Years Education, 20 (1), pp. 30-42.

Roberts, N., 2019. The school curriculum in England, London: House of Commons Library.

Rogers, S., 2011. Play and pedaggoy: A conflict of interest?. In: Rethinking play and pedaggogy in early childhood education: Concepts, contexts and cultures. London: Routledge, pp. 5-19.

The UK Education System. (April 23, 2020). Expactica. Retrieved on May 5, 2020, from https://www.expatica.com/uk/education/children-education/the-uk-education-system-106601/

Tickell, D. C., 2011. The Early Years: Foundations for life, health and learning, s.l.: s.n.

Tower Hamlets, 2019. Early Years Foundation Stage. [Online]

Available at: https://www.towerhamlets.gov.uk/lgnl/education_and_learning/childcare_and_early_years_educ/Early_Years_Foundation_Stage.aspx

[Accessed 15th May 2020].

UK Education System. (n.d.). International Student. Retrieved on May 5, 2020, from https://www.internationalstudent.com/study_uk/education_system/