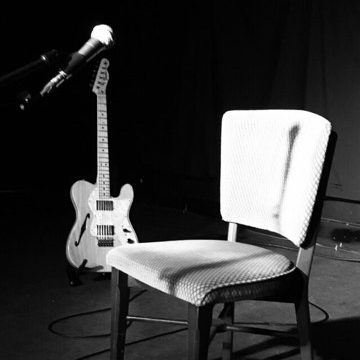

Jesus, where do I start with Kristin Hersh? This is going to be the hardest bit of this to write. She is slippery and phantom like. She never stands still. She is ambiguous and all powerful. If someone asked me what 4AD looked like and sounded like, it would be a glance at her shadow or a brief look through the emotional and intellectual kaleidoscope you get from her music, writing, art and performances. This isn’t even the first time I’ve tried to write about her. In the collection I mentioned earlier, Music, Memory and Memoir, I wrote a chapter about her book, Paradoxical Undressing, a book that revisits a massive year for an 18-year-old Kristin and her colleagues in Throwing Muses. Hersh rewrites her teenage diaries and works in impressionistic fragments of memory and abstract moments of lyricism from her prodigious output. It’s a remarkable book. Half the battle when writing critical analysis about it was in avoiding gushing praise. Part of me wanted to write a chapter that simply said, ‘this book is fucking brilliant’ and leave it there. Reading that book for the first time was something of a personal and professional epiphany. I’d always seen music books as a sort of hobby or as summer pleasure. They were a far cry from material I taught each week and a billion miles from the American war fiction that filled my PhD. Somehow, books written by musicians or about musicians seemed unworthy of serious thought. Years of studying in various lit departments had ingrained a kind of canonical snobbery in me that meant reading 500 pages about the history of Creation Records or an even longer oral history of the Seattle boom felt like cheating. These books were the copy of the Beano that I had to hide inside my broadsheet newspaper. Paradoxical Undressing changed that. It’s innovations and stylistic adventurousness could not be described as anything other than literary. It’s commentaries on mental health, work, creativity, culture and the beauty of unfinished products lend themselves to discussions that equal those found on any reading list (I actually include the book on an MA module that I run now). It bridged the gap. Admittedly, this was a gap that I had constructed myself. It was a space between what I felt I should be reading and teaching and what I wanted to read. This book meant I could engage with what I loved and what I do for a living. I’d always envied academics and teachers who sort of loved their work in ways that I could never manage. Don’t get me wrong, I adore teaching and reading carefully and thoughtfully are the only things that can save us all now. But this book was the first that meant the piles or old records and a life spent in gigs could be interwoven with seminar rooms, curriculum decisions and my research outputs. The book was also the spark for my work with Rob and Helen. They had been having the same kind of responses to a range of other texts by figures like Tracey Thorn, Tom Hingley and Cud. Our corridor chats tuned to plans and, hey presto, a mere three years later we had a book. The Hersh influence on that book doesn’t end there either. Halfway through putting it together, Me and Rob and our wives Nic and Julia went to see Kristin Hersh perform at the Crescent in York. I always say that gigs are better than they were (this has got much worse since Twitter) but this one was genuinely life changing. She read pieces of creative writing, played those trademark compositions with their odd tempos and frightening lyrical pictures and made us all laugh a lot. She sat on the tiny stage on a big stool and fucking owned the room. It was serious and stupid. It was studied and adhoc. It was highbrow and punk. Julia took a picture of her guitar and this now adorns the front cover of our book.

I won’t go into loads of detail about Paradoxical Undressing here (you can read the book for that) but there is one thing that I need to mention. The second half of the book sees Kristin and her band (including half-sister Tanya Donnelly) trying to get Throwing Muses to make the leap from popular local outfit to a band with a deal. The problem is, as I’m sure many bands have found, that record label A&R men are mostly wankers. The band have dinners with them, and they come away deeply unimpressed by the ‘orange men’ and their coked up hubris. The industry stinks. It wants creative control and aesthetic final say. It’s all money and ego and the antithesis of the band’s playful authentic spirit.

Apart from one bloke who makes polite enquiries on the phone. Apart from one bloke who wants to give the band a chance on their own artistic terms. Apart from one bloke whose patience and good manners help the band make a seismic recording. Apart from one bloke who sits in opposition to all the egomaniacal nonsense usually associated with label visionaries and Svengalis. An unassuming bloke with a weird name.

The quiet determination and artistic single-mindedness that define Ivo Watts-Russell are a blessed relief from the situationist superiority espoused by Tony Wilson at Factory and the childish drug boasts that always accompanied the success Alan McGee forged with Creation. Please don’t misunderstand me, I love both of those labels and their products sit proudly on my record shelves and in my t-shirt drawer. It’s just that I know deep down that the two men in question would not be my cup of tea. I’m a bit old fashioned and quite like modesty and decency. Hubris fills me with trepidation and people banging on about their epic pill binges are as dull as dull can be. Kristin Hersh gets this. Her book is full of tales in which Ivo’s strange sense of humour and sideways take on the world around him chime with her own. To Kristin, his disembodied telephone voice belongs to a ‘six-year-old in a bowler hat’. His creative and critical singularity come from a ‘misguided angel’.

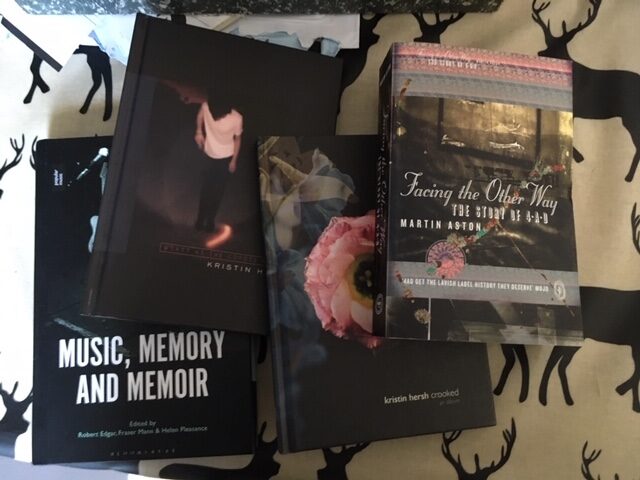

In the summer of 2015, I submitted my PhD thesis and about a fortnight later went to the lovely Greek island of Samos for a week of sun, feta and colourful booze (I also got loads of mosquito bites thrown in for free). Whenever I go on this type of holiday, part of the pleasure is a big stack of thick books. These are usually books you can lose yourself in. They have intricate plots and Dickensian caricatures. Often, this will be a big American novel by someone like John Irving or Donna Tartt. For this holiday though, I wanted to get away from American fiction for a bit (and certainly from issues around violence, masculinity and myth which I had been struggling to theorise in my thesis for the previous four years). I chose music writing. As I said above, until I read Paradoxical Undressing, music writing was always an escape hatch. So, instead of a stonking great multi-generational New England saga or dark tales about stolen paintings or fucked-up university students, I went for a pile of label histories. I took David Cavanagh’s, My Magpie Eyes are Hungry for the Prize: The Creation Records Story, Mick Middles’ Factory: The Story of the Label and Martin Aston’s Facing the Other Way: The Story of 4AD. These three books comprise just short of 2000 pages of detail, analysis, gossip, myth and scandal. Yep, you guessed it. The label histories and the big novels are pretty much the same. I should have clocked the word ‘story’ on all three covers; it was a bit of a giveaway. McGee, Wilson and Watts-Russell may as well have been Twist, Copperfield and Nickleby. These are three picaresque figures defined by their creative drive, their terrible business decisions and their folk hero status. They tumble through the texts making friends and enemies. Their bands’ output is their alchemy and the aesthetic of the label becomes an indelible cultural stamp. The one difference is that, unlike McGee and Wilson, Ivo Watts-Russell sounds like a nice bloke. The bristling world of revenge, machismo and competition is not really for him. He is a quiet man surrounded by great artists. He’s not a wanker. Here’s how Martin Aston describes him and his label in the introduction to his book.

“Ivo-Watts Russell was more of recluse than a media-savvy self-promoter, and 4AD had no recognisable ties to the zeitgeist – nor to any cultural trend, in fact. All of that, Ivo felt, was irrelevant; only the artefact mattered – the music and its exquisite packaging.”

Aston devotes a healthy chunk of his book to the coming together of Throwing Muses and Watts-Russell and his initial description of the man is borne out in the way that both parties recount their conversations. Hersh told Aston that, ‘Ivo and I would talk about everything but the music industry, which was easy because that didn’t interest either of us’. Their conversations instead included ‘rose diseases, interesting animals, crazy shit that we saw’. As in Paradoxical Undressing, Hersh makes it clear that ‘he was essentially a child in a man’s body’. From Ivo’s perspective, it is those fabled oppositions and complexities that attract him to Throwing Muses and suggest that they would make an ideal fit for the label. The music is ‘hard and aggressive’ but also contains ‘beauty’.

My ears are far less sophisticated than those belonging to label wizards, but I can hear that Throwing Muses are certainly weirder than anything else I’ve tried to describe here so far. The four band members, Kristin, Tanya, bass player Leslie Langston and drummer Dave Narcizo pull in different rhythmic directions. Songs make sonic and thematic handbrake turns. It is indie but also something stranger and murkier. Songs explore spatial constructs, blurred memories, the pain of desire and the intensity of artistic creation itself. They are melodic and sweet but then jarring and angular. All of these things take you by surprise. I must have listened to Hunkpapa, for example, (it’s literally on my turntable as I write this) at least a hundred times but the switches still catch me out. Sometimes this happens within songs and sometimes in the curation of the LP itself. Angel is about as near as the record gets to a conventional pop song but then this is followed by the trippy country punk of Mania. Kristin’s voices runs up and down a scale. The song drops away to a claustrophobic bass line and then builds again with spiralling guitar and frenetic drum patterns. Its fucking frightening. It’s also fucking clever. Never ever could you just pop this on. Throwing Muses records demand your attention and your participation. Get involved and make sense then, when you listen again, abandon all of those ideas and start again. They challenge you and confront you. The music is an encouraging punch in the face and an addictive kick in the ears.

Then, of course, there is the Tanya Donnelly factor. To use another Venn diagram (I really like them), she is the centre of Breeders, Belly and Throwing Muses. The three bands sound very different but are glued together by her song writing and musicianship. Her melodies are sweeter than Kristin Hersh’s but her guitar playing is more abrasive and sonically challenging than either of the Deal twins. She carries that same complexity that I’ve been banging on about the whole time. Nowhere is this clearer than in the magical Not Too Soon. Most Throwing Muses songs are Hersh compositions and are brilliantly fucked. Just see the analysis above for why. In 1991, the Real Ramona LP contained three songs written by Tanya Donnelly and Not Too Soon is one of them. It’s a stone cold indie pop belter. It has perfect vocal interplay, a festival-friendly melody and gorgeous warm production. So far, so good but where is the trademark complexity? Where are the odd turns? Well, they are right there in the chorus. It doesn’t have any words. It has Tanya making sort of growly, throaty noises. They follow the melody of the guitar and sort of make fun of it. So, like the video for Safari, this is a band who can make perfect pop music but make fun of it in a kind of meta way. Writing a great guitar hook and then showing how absurd great guitar hooks probably are is about as 4AD as you can get. The artists take their music seriously but are self-aware and witty enough to also poke a tongue out at themselves for being such muso bores.

As I’ve tried to make clear, these oppositions, paradoxes and oxymorons are what I relish in art generally and in 4AD’s roster specifically. The music makes me work hard. It’s approach to releases means that my senses run smack into each other. To see is to hear is to feel is to read. As a fan, this is an endlessly renewing thrill. As someone who works with words, it’s a chance to try and shape all of this into critical and intellectual arguments. I think I’m getting there with this but there are still mistakes and fuck ups ready to be made.