by Daniel Collins

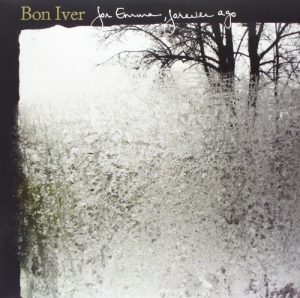

Justin Vernon, under the name Bon Iver, released the album For Emma, Forever Ago on 8 July 2007. The album was recorded over a three-month period at his father’s hunting cabin, an hour’s drive north from his hometown of Eau Claire. Vernon retreated to the cabin to evade the ‘responsibilities of adulthood’ following the break-up of his band, DeYarmond Edison, the deterioration of a relationship and various gambling and health problems he was suffering at the time. Vernon emerged from the cabin at the end of February 2007 with 37:19 minutes of audio, eight tracks worth, and the belief that this was a good basis on which he could start production (Avclub.com 2008) – ‘they were demos for an album I might re-record’ – eventually deciding after persuasion from friends to use the ‘demos’ as the finished product. The creation of the album proved to be a cathartic experience. On its release the album charted in eight countries, going Gold in England and America and Platinum in Australia, demonstrating the album’s positive reception and providing Vernon with the breakthrough he had sought. With this essay, I will make an in-depth analysis of the choices made by Vernon in his performances and the production of the album, exploring how an album which strayed from traditional, accepted production standards achieved, and still maintains, commercial success.

Vernon’s role as producer came at a time of societal shift in the music industry, where the accessibility and advancements of technology resulted in a further breakdown of the stereotypical boundary between artist and producer. Up to this point a few artists such as Brian Wilson had written, recorded and produced their own work, but most artists relied upon producers to guide them towards their artistic goals. However, this could result in considerable influence from the producer and the artist losing control over their vision.

The blurring of these boundaries gave rise to a new kind of ‘DIY’ (Do It Yourself) producer, one which author Richard Burgess (2013, p. 9) labels in his ‘functional typologies’ as the ‘artist producer’. This sees the role of musician and producer merged into one, the artist now empowered to have complete artistic control from concept to fully realised product ready for commercial release, extending the creative process beyond the realm of production into post production. Burgess (2013, p. 9) states that a pivotal factor for the rise of the artist producer was the ‘democratising effect of digital recording’. For the first-time musicians, could purchase industry standard equipment at a reasonable price and learn the trade from the comfort of their own home.

The concept of a DIY producer is something that resonates with Vernon, who acknowledges Springsteen’s Nebraska and Dylan’s Basement Tapes, both albums being written, performed and produced by the artist in question, as being (Avclub.com 2008) ‘…. huge influences on me. It’s important that I make the records. I engineer them, I mix them’.

Considering the three modes of professional practice identified by Kealy (1979) in his career up to the production of For Emma Vernon had managed to avoid the ‘craft union’ mode, all his previous work being self-produced, and his being self-taught in an informal environment appeared to place him into the entrepreneurial category. However, For Emma, Forever Ago puts Vernon firmly into the ‘art’ category.

The recording studio is an extension of the mixer’s creative arsenal’. These words by musician Brendan Anthony (2017) emphasise the importance of location and its influence in shaping a musical product. The importance of the recording environment is also recognised by author, William Moylan (2015, p. 332) who notes the importance of location claiming that environments often serve to enhance the sound qualities… they enhance the aspects of the spatiality’ identifying the potential of a location to shape the sound and the character of a production. Implying that the function of a location reaches beyond an aesthetic value. The location can also influence decisions made by the artist, in this case ‘artist/engineer/producer’, on a personal, emotional level. This is especially true for Vernon while working on this album, taking into consideration his physical and emotional state.

The importance of location when discussing For Emma cannot be underestimated as the concept of one man recording in isolation in a cabin is something that has indeed become synonymous with this album and is a crucial factor for how the listener understands and interprets the album. Producer Zach Hancock (2011) acknowledges this in his opening line in the documentary Press, Pause, Play when he states ‘Bon Iver made that record in a cabin, it’s one of my favourite records’. It is interesting to note Vernon’s (Avclub.com 2008) own view of the album’s creation, ‘there’s a lot of people that wish they could move to the woods for a few months’. This suggests that the opportunity to remove oneself from everyday life and its problems is not a luxury that can be afforded by many, especially when that time is used on an artistic endeavour.

Vernon’s isolation is important to the album since he can explore and express all his feelings and emotions without influence or embarrassment when producing his music. Hancock (2011) acknowledges this when suggesting it would be interesting to see ‘how it would have sounded if 20 people had made it’, certainly the other 19’ people could never have understood how Vernon felt at the time. Vernon (2008) observed ‘maybe the whole thought of going to a cabin for a few months is something that people relate to as they hear the songs’. The background of isolation and the aesthetic nature of a hunting cabin is something that resonates with the listener on an emotional level, allowing he or she to romanticise the notion of personal isolation in the studio in the belief it could indeed create art of beauty and interest.

The influence of the location takes on more importance when considering the minimal amount and technical limitations of the instruments and equipment that Vernon had to hand since he did not plan to record any music at all, he had just piled all his worldly goods into the back of the car prior to the hour’s drive to the Cabin. Vernon (2008) said ‘I didn’t go up there to make a record but music was just part of the process of me ironing out the weird vibe inside me’. He simply sat and drank beer, chopped logs and hunted for food for two weeks before feeling the need to set up the recording equipment that happened to be in the back of his car. The instruments played by Vernon consisted of a 1930s National Duolian resonator guitar and a 1960s Sears catalogue Silvertone Archtop single humbucker pick up electric guitar bought cheaply on eBay. Despite the album’s popularity, cult status and several interviews with Vernon on the subject, there is still no definitive inventory as to what instruments he had beyond the aforementioned guitars.

Vernon’s recording chain consisted of a Macintosh computer, a Pro Tools interface and a single SM57 microphone. This apparent lack of resources led to what Zagorski- Thomas, (Hepworth-Sawyer et al., 2017) rather negatively, dubs ‘creative abuse’ – the deliberate breakdown of tried and tested recording methods to suite the scenario. This is shown through Vernon’s enforced use of his single SM57, a dynamic, cardioid microphone normally used for recording drums and amplified instruments. This microphone was used exclusively to capture every aspect of the album. The use of a single microphone to record a complete album is unorthodox for a multitude of reasons, especially considering most producers/engineers feel compelled to use multiple microphone types and combinations to capture sounds which can be used in isolation or blended to create interesting timbres for the listener.

Author, William Moylan’s (345, 2015) statement ‘microphone placement can be as critical as microphone selection in shaping sound’ underpins this. The acoustic guitar is presented as a prominent feature across the entirety of the album which comfortably sits in the genre of Indie Folk. To ensure that a guitar becomes what Russ Hepworth-Sawyer and Craig Golding (2011, p. 53) would dub the ‘main feeder’ of the mix, most producers would perhaps opt for a stereo pair that would capture a more detailed sound and a width that would then be panned. Although intended to be of demo standard only, Vernon shows a disregard for industry standard techniques with his use of a single source capture (mono recording) which is then multi tracked and then panned accordingly to achieve width. This is a case of the artist/producer working within, and yet making the most of, the limitations of his equipment.

The limited inventory of equipment acted as an enabler for Vernon to create a unique sonic imprint for the listener, something that is acknowledged by fellow producer and self-confessed fan of the album, Guy Seffret (2011), who discusses his own experiences when recording: ‘I run into more problems the more options I give myself’. Vernon’s limitations appear to spark creativity through his application of auto-tune, software used to correct faults with pitch to improve the perceived performance for the listener. However, Vernon alters the function of the software, allowing it to create new and interesting harmonies which can be heard in ‘The Wolves act I and II’ (at 2:58).

Vernon (2017) speaks favourably of the DAW (Digital Audio Workstation), going as far to label Pro Tools as his ‘musical voice’. Vernon’s comment reinforces Andrew Brown’s (2012, p. 6) thoughts on the computer as a tool for creating music as he speaks of ‘the computer as a musical tool, the computer as a musical medium and the computer as a musical instrument’. In Brown’s view the DAW is not a passive object and has great influence in the shaping of both the compositional and production processes. It can help present the track in a certain way that may go beyond an artist’s initial expectations or intentions. Vernon (2017) acknowledges this through his comments on Pro Tools, ‘I enjoy being able to open up a session, blank tape so to speak, and just create environment’. It is interesting to see Vernon drawing a clear analogy to the process of analogue recording, the whole album being recorded digitally in an ‘analogue’ environment. However, the empowering nature of the DAW appears to attract Vernon (2017) as he suggests that the act of using an instrument as a creative input for song writing is now outdated: ‘With the guitar I used to sit down at a desk and use that room I was in and sing but when I’m looking to write a new song now I’m waiting for an environment to sort of be created accidentally so that I can just step into it’. The DAW acts as a translator between both artist and listener, allowing the artist to convey the in-depth conscience of their art, resultantly allowing the listener to feel a greater connection with the album.

It is important to note that the final mixes of For Emma were initially viewed by Vernon to be no more than a set of demos to be re-recorded in the studio later in his career. The fact the tracks were demos implicates a sense of personalisation to the recordings through their rawness and the vulnerability embedded into the songs at this stage in their development.

Allen Moore (2002, p. 210) states ‘intimacy and immediacy tend to connote authenticity’, suggesting one of the ways in which an artist is deemed authentic is based on the experience he/she provides the listener with. Certainly, all the tracks on For Emma are startling in the levels of their intimacy and immediacy.

Vernon’s use of the first and second person narrative within the album’s lyrical content provides an experience for the listener through what Moore dubs (2002, p. 214) ‘authenticity of expression’. The personal nature of the lyrics provides an almost ‘diary entry’ like feel emphasising that Vernon’s identity is not distanced from but firmly imprinted into the album, adding a sense of truism. Producer Moby (2011), acknowledged the difficulty of appearing authentic when he said ‘the connection (between artist and audience) now has to be a lot more genuine’. It goes beyond having a hit single to resonate with an audience. The use of DAW allows, in theory, anybody to create music in any situation or environment. However, it does not in itself guarantee success, or of making any sort of connection with an audience. Vernon manages to do both.

Authenticity is reinforced through Vernon’s ‘novice’ mistakes across the entirety of the album. These include various timing issues, frequency build-ups and plosives to name a few, all of which are signs of an ‘amateur’ production. Producer Moby (2011) voices, in the Press, Pause, Play documentary, his disapproval of digital art, stating, ‘I personally find perfection in art and music off putting’, and that it is the ‘imperfection and vulnerability of humanity’ in art and music that resonates with him as both a producer and a listener. Taking this view into consideration the naivety of Vernon’s production standards on For Emma further add to the sense of authenticity. Moby also points out similarities between Vernon and Nick Drake, suggesting perhaps that the demographic of this genre is more forgiving of production standards if the music feels authentic and the ‘connection’ is there.

Vernon utilises the sonic environment and sound stage in the post production process to both heighten and expand upon the emotions stimulated by the songs. However, it is important to remember that a listener’s interpretation is subjective and is entirely dependent on their perception of and relationship with the album. Ruth Dockwray (as cited in Hepworth-Sawyer and Hodgson, 2017 p.53) dubs this interpretation of the mix as the ‘relationship between the listener, persona and sonic environment’, the listener becomes the final part of the production process, fusing with the technical and emotional components, creating for that listener a singular, unique experience.

Anthropologist Edward Hall (1968, p. 83) coined the term ‘proxemics’ to refer to ‘man’s perception and use of space’, identifying four zones, intimate, personal, social and public. Across the album, Vernon’s vocal performances may be placed within the ‘intimate’ to ‘social’ regions of Hall’s ‘Proxemics Zones’, arguably only once entering the ‘public’ zone at 4:11 in ‘The Wolves act I & II’. Vernon’s distinct lack of processing techniques such as reverb and delay on his vocals and guitar in ‘re: stacks’ and ‘Flume’ suggests that he wishes for them to have prominence in the mix, as the effects are commonly used to artificially create space. The vocals are pushed to the front of the soundstage, and depth and width is achieved through multi tracking and volume automation, preserving the ambience of the cabin while maintaining a natural perception of width and depth. The intimate nature of the recordings is enhanced by the group of vocal sounds known as ‘alternants’, discussed by Serge Laccase (2010) who noted their wide use in musical contexts, and that they may be identified as placing the vocals in the intimate or personal zones when highly audible. These characteristics include ‘inhalations and exhalations and gasps’, all of which are present in Vernon’s vocals, and, although not a vocal distinction, at 1:29 in ‘The Wolves’ Vernon can be heard scratching his beard, firmly placing the performance in the intimate zone as do the string scratches, chair creaks and finger taps on the guitar sound board. The later addition of the siren pushes ‘The Wolves’ into the ‘public’ zone, somewhat destroying the authenticity of the ‘cabin’ in the woods feel – yet is accepted without criticism by Vernon’s followers, emphasising the personal connection made. Therefore, in terms of staging it is important that Vernon’s vocals and guitar remain prominent at the front of each mix as they ultimately represent Vernon as the sole core of the album, percussion and other organic instruments being used as subtle reinforcements of Vernon’s presence.

Vernon’s ‘crafting’ of the album provides the listener with a greater understanding of its narrative, most notably through the eponymous track, ‘For Emma’. The decision to name the album after the track demonstrates to the listener that Vernon is fixated on the concept of ‘Emma’, an ex-lover, acting as a metaphor for what he (2009) dubs ‘a place you get stuck in’.

Literary theorist, Gérard Genette (1980, pg. 25-26) states there are three types of narrative,

- The telling of ‘an event or series of events’

- The succession of events themselves

- The event that consists of someone recounting something.

All three types of narrative are used throughout the album and the track ‘For Emma’. It is important to note that in the sleeve notes of the album Vernon tells us that this song is set out as a play, allowing us to witness a conversation between himself and ‘Emma’ about the deterioration of their relationship.

Vernon reinforces the notion of narrative between the characters with the use of production techniques such as panning (the process of moving audio within the sound stage) adding realism to the exchanges. This is presented to the listener through double tracked vocals, both panned opposite, off centre. Vernon’s decision to pan these vocal parts reinforces the width between them and both vocals have different timbres, the one on the right being slightly softer than the one on the left, allowing the listener to further differentiate between the two. The decision to pan lead vocals off centre is unusual as most productions would place them on centre, giving them a prominent aspect, as the vocal is arguably the important feature of a track. Vernon’s unconventional spatial placement underpins Serge Laccase’s (2004, p.4) observation that the placement and processing of vocals in either mechanical or electrical processes are ‘presumably to produce some effect on potential listeners’.

The narrative of the song perhaps indicates that Professor Aaron Liu-Rosenbaum’s (2012) view of ‘protagonist’ and ‘antagonist’ is not universal and only applicable in certain contexts. Throughout ‘For Emma’ there appears to be no direct protagonist or antagonist in the track’s sonic narrative. It could be said that the production choices emphasise Vernon’s mental state. The ‘sonic narrative; is created around the natural characteristics of the production, allowing the listener to form their own interpretations. This supports Filimowicz and Stockholm’s (2010, pg. 13) theory that ‘sounds can be interpreted or experienced as characters in a story’.

The music acts as an extension of the narrative, emphasising an emotional connection with the listener beyond the lyrical content. However, this is less overt and dependent entirely on the listener’s perception. An example of this is the instrumental bridge in ‘For Emma’ where the instruments mirror the conversation between the two ex-lovers. This is achieved through Vernon’s later decision to add multi-tracked brass, providing a sense of warmth and richness to the soundstage, reflecting the positive aspects of the relationship. However, when the brass section breaks off into individual solo parts, the section becomes disjointed (2:30) and falls back into the mix, perhaps representing the conflicting nature of the relationship.

At this point the slide guitar, a sad, plaintive sound, arguably representative of the doubt and negativity in the relationship, becomes more prominent. Vernon’s use of reverb directly inserted onto the channel strip ‘muddies’ the track, distorting its position within the mix, making the brass appear less prominent but still lingering at the back of the sound stage perhaps suggesting his thoughts on the relationship still occur from time to time.

No matter how the album is perceived, from a critical, analytical standpoint or simply as a listener, it is unique. We may be able to pick apart the work and discover what Vernon did, but will never be able to fully understand why. The circumstances surrounding the actual recording, Vernon’s state of mind and the total lack of preparation and planning could never truly be replicated.

References

Anthony, B. (2017). Mixing as A Performance: Creative Approaches to The Popular Music Mix Process. Journal on the Art of Record Production, 11.

Avclub.com (2008) Justin Vernon of Bon Iver. [online] Available at: http://www.avclub.com/article/justin-vernon-of-bon-iver-14201 [Accessed 1 Apr. 2017].

Brown, A. (2012) Computers in Music Education. 1st ed. Hoboken, Taylor and Francis.

Burgess, R. (2013) The art of music production. 1st ed. New York, Oxford University Press.

Filimowicz, M. and Stockholm, J. (2010) Towards a Phenomenology of the Acoustic Image. Organised Sound, 15 (1).

Genette, G. (1980) Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method, Ithaca, Cornell University Press.

Hall, E. (1968) Proxemics. Current Anthropology, 2 (3).

Hepworth-Sawyer, R., Hodgson, J., Paterson, J. and Toulson, R. (2017) Innovation in music II. 1st ed. London, Future Technology Press.

Hepworth-Sawyer, R. and Hodgson, J. (2017) Perspectives on Music Production: Mixing music. 1st ed. New York, Routledge.

Hepworth-Sawyer, R. and Golding, C. (2011) What is music production? 1st ed. Amsterdam [etc.]: Oxford, Elsevier.

Kealy, E. (1979) From Craft to Art: The Case of Sound Mixers and Popular Music. Work and Occupations, 6 (1).

Lacasse, S. (2000) ‘Listen to My Voice’: The Evocative Power of Voice in Recorded Rock Music and Other Forms of Vocal Expression’. PhD thesis, University of Liverpool.

Laccase, S. (2010) Persona, emotions and technology: the phonographic staging of the popular music voice. 1st ed. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Moore, A. (2002) Authenticity as authentication. Popular Music, 21 (2).

Moylan, W. (2015) Understanding and crafting the mix. 3rd ed. New York, Focal Press.

Press Pause Play (2011). [film] Austin: David Dworsky, Victor Köhler.

‘Sound breaking: Stories from the Cutting Edge of Recorded Music’. (2017).

Sound Breaking.

Sweeney, S. (2009). Justin Vernon Is Going Home. [online] The New Yorker. Available at: http://www.newyorker.com/culture/new-yorker-festival/justin-vernon-is-going-home [Accessed 1 Apr. 2017].

Songs/Albums Discussed

Dylan, B. (1975). The Basement Tapes. [CD, Vinyl, Download, Cassette] Columbia Records.

Springsteen, B. (1982). Nebraska. [Vinyl, CD, Download, 8-track, Cassette] Columbia.

Vernon, J. (2007). For Emma, Forever Ago. [CD, Vinyl, Download] Jagjaguwar, 4AD.