by Tom Knevitt

Introductory Simplifications

First things first; in the interest of clarity throughout the course of this research article, I think it best to make the distinction from the off over the subject matter referred to by the term ‘Pop Music’ (or ‘Pop’ for short). Put plainly, this essay hopes to focus on the songs to be found specifically within the current chart climate, and not those that attach themselves to the vaguer term ‘popular music’. As a clarification point that has been investigated by the community charged with ontologizing music and its many textures thus far, the latter of the two phrases is widely seen to encompass a number of musical genres, and is therefore more so defined as any musical product that appeals at any one period to a significant number of people. This may – and often does – include genres ranging from EDM to Hip-Hop, as each has capability of appeal on a large scale. Academically, the clarification of Pop as a genre (or indeed, as something undefined) is largely contradictory – often, Pop is classified by way of opposition (typically in reference to Rock Music, which acts as an ambassador for an opposing musical ideology). Such an acknowledgement of this ambiguity is noted by Grossberg (1992, p. 206), who states that the conflict ‘distinguishes between musical/cultural practices and between fans, although the two dimensions do not always correspond. It can be marked a number of ways: inauthentic vs. authentic; center vs. margin; mainstream vs. underground; commercial vs. independent; coopted vs. resistant; pop vs. rock’. Other ontology – expressed here by Shuker (1994, p.7) – groups Pop and Rock as one, though still reverberates the judgement of Pop as that built to specifically cater to mass needs:

In sum, only the most general definition can be offered under the general umbrella category of ‘pop/rock’ […] Indeed, a purely musical definition is insufficient, since pop/rock’s dominant characteristic is a socio-economic one: its mass production for a mass, predominantly youth, market. At the same time, of course, it is an economic product which is invested with ideological significance by many of its consumers […] it is misguided to attempt to attach too precise a meaning to what is a shifting cultural phenomenon.

It is this mantra that I wish to allocate to the genre of Pop in this article; as such, ‘Pop’ is constituted here and now as music that is chiefly constructed – or ‘manufactured’, as it were – as a means for its short-term profitability. Think ‘disposable’. Think ‘chart’. Although a hazy clarification at best – and one which will later present itself again as argument in the topics being explored here – a simplification at this point should hopefully spell out the mind-set necessary for tackling the issues presented hereafter.

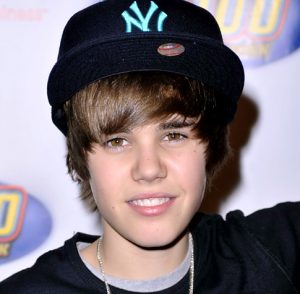

Secondly, in reference to this, I offer an explanation as to the use of Justin Bieber as the central figure upon which to explore the upcoming set of ideas in relation to the make-up of modern Pop. Since his discovery – and subsequent signing – by Usher (and co.) as a young talent back in 2008, Bieber and his musical output has operated predominantly and coherently within the definitions outlined as ‘Pop Music’ above. Although just one of a multitude of artists who also create musical products in this fashion today, Bieber’s discography offers a selection of musical circumstances that may prove effective when looked at together in highlighting the collective nature of Pop’s current workings. Investigating such a history, I hope to first give thought towards Pop’s compositional model in reference to its conflict from normalities found elsewhere in music creation, before looking outward to peer over Pop’s aesthetical characteristics in the search for any definers of modern success.

An Anatomy of Discography

Proving to be anything but straightforward, the current diversity within Bieber’s short musical career thus far leaves it opportune for academic comment. In a further attempt to bring you, the reader, more up to speed with the reference pool from which I hope to make examples of throughout, up next is a brief summary highlighting the more beneficial illustrations of Bieber’s present output, as follows:

Central to Bieber’s discography is his seminal EP and three subsequent solo LPs: My World (2009), My World 2.0 (2010), Believe (2012) and Purpose (2015). Each is built as an amalgamation of a selection of composers and producers, though in all cases Bieber is sold as the sole protagonist at large (excluding featured artists).

Released a year after his debut album, Under the Mistletoe (2011) presents itself as a ‘Christmas covers’ effort. Something of a novelty, the album is comprised for the most part of reworked versions of classic Christmas anthems (‘Santa Claus Is Coming to Town’, ‘Drummer Boy’, ‘Silent Night’ amongst others), brought into line with an updated demographic by way of a little Bieber sparkle.

My Worlds Acoustic (2010) and Believe Acoustic (2013) present the songs of their counterpart albums as stripped-back renditions, swapping out production gimmicks for a more minimalist presentation aesthetic, and shifting focus towards more intimate vocal avenues.

Lastly, Journals (2013) was released prior to Bieber’s latest (and vastly divergent) solo LP. Marketed as a compilation album, the record acted as a pivotal transition for Bieber in a bid to define his own ‘sound’. Taking charge as Executive Producer, Bieber recruited in a raft of R&B talent in order to construct the musical work, vying for a freedom in which to define himself as an artist, to the point of major label conflict, (– more on this later).

Having covered all introductory bases, we are subsequently presented with the solid groundwork to investigate the connections made between the solo star and the far larger framework for Pop construction – I hope to draw from of a number of these audio examples to make comment on Pop’s functionality in relation to society today as this article progresses into thought.

The Collage of Collaboration

To begin at the beginning – in more than one respect – we first look to consider the compositional nature of Pop using Bieber’s earliest output as our bedrock. From the off, doing so illuminates a key imprint of Pop’s construction: the ethos of collaborative composition. As is found throughout Bieber’s discography, and indeed that of Pop’s artist majority, the genre shows a keen tendency towards the practice of joint song manufacture through the use of specialist Pop writers and production teams, oft times excluding the ‘artist’ in the creative process altogether. As an example of this: spanning the seven tracks found on Bieber’s My World EP, we may list upwards of thirty different collaborators (namely those credited as writers and producers of the musical content contained within (– via My World‘s sleeve notes (2009))). Such an approach to manufacturing houses a relatively straightforward appeal as far as profitability is concerned; in a bid to gratify the predictable and largely uncomplex wishes of its audience, Pop seeks to culminate the core donations of its potential contributors in a bid to maximize audience appeal, and as a result, a great deal of Pop records now come into existence by way of this collective collage of materialization. (I advertise ‘One Time’ (2009) as a sonic reference if need be).

The first striking translation of such a procedure is the sheer contrast that it exhibits to our original models of performance documentation. Historically, musicologists have generally accepted the phonograph (and thereby the wider concept of early record production) as a means to preserve a real-world performance as a tangible substance. Going hand-in-hand with technological developments since that time, we have steadily accepted the credible deviation from such an outlook as new tools for creation have allowed music-makers to bring about and adapt new ideas less-so tied down to straightforward performance capture and playback. Before long, our compositional practices followed suit, ‘making possible the total studio production in which no live performance in toto takes place’ – as noted by Jonathan Tankel (1990, p. 37) in his article ‘The Practice of Recording Music: Remixing as Recoding’. In Pop’s workings, however, we step even further, and find ourselves presented with musical products that negate the initial documentary aspect of record production altogether. Fundamentally, an innate characteristic of this collaborative approach is the blurring of lines that once separated composition, arrangement and production parameters in the creation of recorded material; this materialization of Pop tracks by way of formulating, piecing together, arranging and producing musical ideas all as one fluid motion carried out between multiple parties establishes a model that bypasses any form of original ‘performance’ to be made palpable. Zak (2012, p.43) observes that this seed of being is one that can be traced back as early as the 1950’s, at such time Pop records ‘went from documentary snapshots representing past events of remote provenance to aesthetic artefacts in their own right, their place and time forever here and now. They were absolved of representational responsibility; the natural sound world ceased to be their primary referent’. Consequently, through such a process, the first time we do hear the (generalization of the) modern Pop song as a ‘performance’ in the understood aesthetical wrappings of its nature is at the point of playback upon its produced completion. In debating the essence of the word performance, Auslander (2006, p.2) offers up two distinct categories for which to discuss our relationship with documentation, the second of which, ’theatrical’, he defines as such:

In the theatrical category, I would place a host of art works of the kind sometimes called ‘performed photography’, […] These are cases in which performances were staged solely to be photographed or filmed and had no meaningful prior existence as autonomous events presented to audiences. The space of the document […] thus becomes the only space in which the performance occurs.

Arguably, this interpretation can be summarized as that which rings true in Pop, and as a result of such, we are forced to consider many Pop tracks as montages that only come into true existence once solidified in the form of their audio products. In this sense, any ‘performance’ aspect that usually serves as the Beginning in our approach to record production can be claimed to have never existed as a real-world entity in the first place, until such time it is then created through an un-documentary medium (– and subsequently by way of ‘live’ adaptations later made by its artist). In concluding this notion, we can therefore utilize Pop as an example of a musical genre that chooses to flip our relationship with the word ‘performance’ completely on its head for its own profitable convenience, leaving the idea of the documented performance well and truly in the past to instead opt to portray the performed document. In categorizing this skewed neglection of documentation in recorded products, Lee B Brown (2000, p. 363) proposes the term ‘works of phonography’, which he describes as ‘sound-constructs created by the use of recording machinery for an intrinsic aesthetic purpose, rather than for an extrinsic documentary one […] The sonic palette out of which a work of phonography is created might contain stretches of ordinary performed music. But it might contain an almost unlimited range of materials that would be out of place in a merely documentary recording’. From this, we see a clear overlap in our identification of the Pop product; challenging our major preconceptions regarding the practice of record production, Pop removes (or reorders) a vital stage of its accepted process yet remains viable as a functional manufacturing model – in this one major respect, Pop seeks to rescind our accepted understanding of music creation to act as an ambassador in this new mode of creative design, and flourishes in doing so.

The Pursuit of Perfection

Thinking chronologically through the production process of Pop, we now venture past our newfound penchant for collaborative composition and arrive with a view to polish and present our gathered material to the world outside. To consider the measures taken to adapt the raw musical components collected at this stage in a bid to gain their admission into the public domain, we reach another tradition altogether. Time to bleach away any flaws.

Our ability to construct the ‘perfect’ take out of any given source material has grown exponentially over the last few decades as a result, too, of increased technological convenience. As a by-product of this, we now observe a threshold in Pop production that sees every discrepancy varnished from existence as standardized practice, leaving instead a visibly flawless rendition of the ideas within our Pop products. Looking again towards our hero at large, it could be said that this area of thought sees itself applied to Bieber’s vocal performance components throughout his discography content above anything else, though the same theory could well be enforced on other aspects found within his songs (i.e. the acoustic guitar work demonstrated more chiefly in the earlier stage of his recorded career). In a reiteration of our compositional transformation, the extent of mediation seen in Pop is in direct contrast to that located in the origins of record production. Elsewhere in his examination of recorded music’s ontology, Brown (2000, pp. 361-362) reminisces back towards the underlying enticer fixed within phonography, that being transparency:

The recording industry has lived mainly by what might be called the transparency perspective, according to which a sound recording is understood on the model of a transparent windowpane through which we can see things undistorted […] The cliché image of Nipper mistaking a recording playback for his master is only the best-known piece of hype the industry has always used to sell the idea that its transparency is a realized fact.

As expressed here, the demonstration of unaltered content found in the earliest instances of musical recording is far from the workings that are grabbed by Pop’s production custom today. Considering the new normality of this Perfect Production aesthetic located within Pop in this day and age, we are forced to permit the questions regarding our audience’s interaction with such a level of falsehood; to what extent is the approach so blindly taken to Pop construction perceived as authentic by its relative consumers, and what protective measures, if any, are being taken by artists to ensure their integral sustainability, thereby maintaining a working relationship with their many prospective moneylenders? One may say that for an inquiry so equivocal as this, the first indication of an answer seems as glaring as can be. Simply put, the sheer ubiquity of Pop (both in its sonic form, and by way of our potent obsession with its many personas) leads us to believe that, for the most part, its function in today’s society is largely unhindered by the common legitimacy concerns that plague and drag down its opposing pool of genres, leaving it unobstructed to perform its underlying day-to-day purpose. In his now infamous depiction of authenticity classification found within ‘Authenticity as Authentication’, Moore (2002, p. 210) notes this idea that authenticity differs from genre to genre, time to time, and person to person, hypothesizing that ‘ “Authenticity” is a matter of interpretation which is made and fought for from within a cultural and, thus, historicised position. It is ascribed, not inscribed’. Subsequently, in a similar setting to our previous considerations on Pop classification-through-opposition (often to Rock), Moore (2002, pp. 210-211) frequently makes reference to the Pop genre as one that positions itself proudly at the rival end of the authenticity scale. He asserts the claim that our ascription of authenticity ‘is, of course, pertinent to the hallowed distinctions between “pop” and “rock” […] there is a sense in which different understandings of authenticity are conflated in the presence of this fundamental authentic/commercial paradigm’.

As is evident, this newfound reality of corrective ease is far from one that seeks to confuse the Pop authenticity sphere exclusively; the same conflict is indeed a minefield that has branched out into the latest offerings found within numerous modern day genre products. Suffice to say, the relative acceptance of fans here in our discussion may chalk up to (and be therefore confined within) the nature of Pop itself as a concept. Speak to any jazz disciple, as an example, and you would expect to find a vastly lower tolerance on their behalf of performance manipulation. So, what is it about the nature of Pop Music that makes way for such submissiveness as far as its audience is concerned? It does appear that the curious functionality of Pop as a musical classification has caused it to establish its own department of ‘easy-listening’ customers with which to appeal to, with both halves now functioning as a symbiosis to everyone’s satisfaction. What is suggested by this is a deep-rooted wilfulness on the consumers’ part in allowing Bieber et al. to supply them with the disposable pleasure engrained in Pop’s mantra, and as a consequence, Pop (at its most pure) can be observed to function under a high degree of self-awareness, basing its offerings on the understanding of this consumer state-of-mind – at such a point, the need for otherwise necessary attempts made by both artists and producers to conceal any prevarications are diminished. Ultimately, in a similar vein that defined the process for Pop composition as one which formulaically hopes to rely on and appeal towards black-and-white, rudimentary tastes, the same can be said for this signature production ideology.

That’s not to say, however, that Pop lives without its authentication perils. To assess the risk involved in Perfect Production from a Pop producer’s perspective, then, is to second guess the relative boundaries of acceptance within the prospective listener. As an industry that relies so heavily on the fierce bond that forms between the idol and their compatible devotees, the prolonged quest for trust between the two parties has given rise to distinct techniques used by Pop acts and their teams to help nurture this requirement of reverence. Taking this notion of perceived authenticity (or lack thereof) fostered by an expectancy to create the flawless musical product, to what extent are we as the Pop production guild now following up this sentiment by forcing an opposing movement to regain (or hint enough at) the credibility to be found within our artist counterparts? Are we now reacting to this recognized audience awareness over the nature of ‘constructed’ productions to additionally offer them a safeguarding alternative? My Worlds Acoustic and Believe Acoustic may suggest as much, as examples in which modern Popstars seem to show their fans an attempt at intimacy via the medium of the ‘acoustic rendition’. Evident by a number of current performers, Bieber’s case is again noteworthy by way of its extensiveness; where the common Pop artist may choose to shoehorn the odd acoustic song into an album as a bonus feature, Bieber (and team) has gone so far as to create two standalone LPs as a platform for such. Some may attribute this as an untaxing method of income generation – be that the underlying aim behind Pop, after all – but what chance is there that by drawing attention to their base competence the artist is thus enabling, or in fact stabilizing a notion of trust between performer and listener, thereby authenticating an excuse to administer the high level of performance manipulation elsewhere in their output? Further than this: would a dismissal, and therefore exclusion, of this type of discography chaff by Bieber’s behind-the-curtains team subsequently bring harm to his functionality within the Pop environment? Perhaps a subtle, albeit persistent when necessary, reminder of Bieber’s inherent performance talent (of which he has in abundance) is every bit as vital to his functionality within Pop as any original compositional episodes.

The fact is that by any standards (certainly those of the undisciplined common folk (as to not define a standardized Pop audience too harshly)), Bieber’s competence as a musician (speaking on behalf of performance skill and refinement) is unquestionable – as is, again, the case for Pop’s artist majority. (As a secondary aid, one may look towards ‘Favorite Girl (Live)’ (2010), taken from his ‘acoustic’ anthology). Under circumstances that would have prevented the luxurious ease of musical manipulation as to so simply alter Pop’s performance components to the degree of absolution, it’s doubtful to imagine a definitive shift in our attitudes regarding performance merit and acceptance, given the understanding that the artist themselves were capable of natural quality. Bieber’s two acoustic offerings prove this to an extent – the manipulative absence coming instead through choice in this instance – as examples of viable Pop products that substantially lack the sky-high expectations of correction perfection. While it is understood that these LPs are not totally free from performance construction, the point to be taken comes from the contrast between production ethos in each pairing. To resolve Moore (2002, p.213) in his input towards Pop authenticity, we can marry up the processes put forward through the acoustic rendition to his coined term: ‘first person authenticity’, by which the sonic output ‘is perceived to be authentic because it is unmediated – because the distance between its (mental) origin and its (physical) manifestation is wilfully compressed to nil by those with a motive for so perceiving it’ – a viewpoint that once again champions the premise of mediation as a key ascribing factor of musical legitimacy. In summarizing the phenomenon of forced intimacy in Pop, I would not hesitate in recognizing Bieber’s acoustic donations (and thus, their surrounding concept) as vital constituents in the functionality of the genre regarding the relationship it has (or indeed yearns for) with its audience. To consider the dominating influence that stems from these Perfect Production expectations that we now face in 21st century Pop – for otherwise-admissible performance components to undergo such a level of doctoring simply to correspond to our accepted expectations of quality – I’d argue that artists now find themselves forced into this acute compensatory practice by the lack of opportunity they find elsewhere to establish such connection-turned-reverence through their conventional product material.

The Textures of Today

Back to the topic at large, and as a point worth factoring into the argument to be had here, neither Journals nor Purpose (Bieber’s latest two offerings) have received this acoustic LP treatment. Mentioned previously in the discography outline, the emergence of Journals marked a turning point for Bieber as he looked to nurture songs and their respective productions under his own say-so, ultimately abandoning his preconceived aesthetical basis to manufacture work more for his own personal taste. As alluded to previously, the choice prompted a backlash from Bieber’s label, who deemed the project too out of line with his designated demographic, and as a result, neglected to grant the album a full release upon initial completion – (consequently, Journals was initially released in a staggered online-only format, before receiving a physical follow-up three years later). Speaking to Fader magazine, chief collaborator on Journals Jason ‘Poo Bear’ Boyd (2015) testifies as such:

I knew they weren’t going to push it because that wasn’t the direction they wanted him to go in […] we were finally going in the direction that Justin for once in his life wanted to go in. We were recording songs that he wanted to record, not thinking about making everybody happy. It was bittersweet […] They respected his creativity as an artist, so we were able to do the record. But they didn’t want to call it an album—they called it Journals. They didn’t allow it to chart on Billboard. It wasn’t the direction that they wanted him to go in, so they didn’t support it.

Following suit from this, Purpose takes the construction approach of its predecessor one stage further, seeing Bieber hand the production reins over to a choice number of high-profile EDM artists – noteworthy overseers of the project come in the form of Sonny Moore and Thomas Pentz (– Skrillex and Diplo respectively), who operate as a newly-formed production duo under the guise of Jack Ü. The result of such a move is an LP that carries Bieber far from his textural origin, housing Purpose in an altogether different space than his seminal work. To pluck one of the abundant examples from the record to use as evidence towards this, I suggest a look at the beat-break on ‘Children’ (2015) (found in place of a vocal-led chorus at 1.01 minutes); it takes but a hint of research (or background familiarity) into the textural preference and production style of Skrillex to notice his handiwork at play here. To address the stylistic emphasis of the album then, one could declare that the sonic appeal found within Purpose exists outside Bieber’s artistic domain, though is still presented under his brand and as such, we deem Purpose to be a legitimate Bieber product as much as any other. Examining his own approach to the record, and the decision to adapt external big-name aesthetics into his work, Bieber (2016) speaks of his shifting methodology as ‘a big departure from what I released in the past […] The music I was making with Poo Bear, Skrillex and Diplo felt right […] We just knew that was the sound we were looking for […] It was a longer road. I didn’t just take what was handed to me. I experimented and took the time I needed to find my sound’.

The definitive production outlook expressed by Bieber in both Journals and Purpose may well demonstrate the latest example of a deviation in our understanding with regards to the importance of conscious texture shifting as a contributor towards the prolonged appeal of Pop artists. This flip in our comprehension can be defined as such: it appears that not too far into Bieber’s past output, the aesthetical nature of his tracks served as nought but a side-effect of the compositions themselves. More recently however, these production textures can now be defined, to a significant extent, as the key shapers of a track’s attractiveness. It is through this latter mode of Pop that the producers – once confined to the shadows as not to distract from the protagonist essence – now are brought centre-stage, to act in tandem with the branded ‘face’ of the music to achieve something truly greater than the sum of parts.

Bieber’s recent trajectory in Pop may reinforce the idea that once firmly established as a trusted musical entity, Pop artists may divert from their accepted musical confines to explore new territories, and that doing so may serve as strategy for sustained relevance towards an ever-shifting audience demographic; through the careful and meaningful choosing of collaborators in his latter-day continuation in Pop, Bieber has managed to shake the natural constraints placed upon him by his peers, by his management, and even by his seminal fan-base. Relating this back to a forced intimacy viewpoint as discussed previously, the absence of acoustic counterparts at this stage of Bieber’s discography may be interpreted as twofold: firstly, that having previously demonstrated his innate authenticity, Bieber is left without need to exhibit any similar form of reminder in tandem to his subsequent work, and secondly, understanding this, Bieber is thus free to permit himself a flexibility to expand his own sonic definitions, unburdened by any chronic danger of audience rejection due to this pre-established devotion.

As is demonstrated powerfully though the make-up of both Journals and Purpose, Pop as a working musical model has the capacity to rely heavily on assimilation, gathering the perks and benefits of other neighbouring genres to then present them under the Pop guise. If questioning the justification of this allowance, it appears that the ‘brand’ associated with Pop acts once again takes responsibility; having already authenticated himself solidly within the social nerve centre of today as a cultural entity, the world seemingly grants Bieber an exemption from musical confinement, therefore giving rise to his ability to shift from ingrained preconceptions into new sonic territories. On topic of production influence in the receptiveness of an artist’s art, Tankel (1990, p. 39) sympathises with this understanding, suggesting that ‘in popular music, the audience will support innovation that resonates with familiarity. More important, innovation in popular music is often sonic rather than musical’. Using their established respect for him as a basis, audiences first find meaning in their stable connection with Brand Bieber and draw from the safety of familiarity to then allow for wilful textural expansion on his part.

At this stage, we can quietly assert the idea that Pop draws substantial character both from signature textural trends and artist personas (or brands) over its many surrounding factors. Naysayers may bemoan this attribute of Pop as one that detracts from music’s true purpose, but to do so would prompt a reminder of Pop’s key aim as a means of commercial profitability. Our customary need to evaluate authenticity, from an academic viewpoint, into the likes of Bieber and his Pop peers indeed relies on this remembrance also – it seems to be in Pop’s inherent nature to exist slightly askew from any and all genres surrounding it in that regard. For my own sanity, I tend to gravitate my definitions of Pop and its unnamed opposition by their duties towards ‘entertainment’ and ‘art’ respectively – in which, on a most basic level, entertainment describes a fulfilment of the audience and art describes a fulfilment of the artist. Referring back to our introductory framework that defined Pop as opposition to ‘the alternative’, Auslander (1999, p.81) echoes this mindset also (hereby using ‘rock’, again, as the definable example of such resistance):

The ideological distinction between rock and pop is precisely the distinction between the authentic and the inauthentic, the sincere and the cynical, the genuinely popular and the slickly commercial, the potentially resistant and the necessarily co-opted, art and entertainment.

Accepting this innate characteristic of Pop, and therefore ceasing to consider it a detraction to its purity in the context of our relationship with music as a whole, is therefore a necessary step in objectifying our subsequent judgement. Doing so conclusively permits texture shifting the esteem it rightly deserves within the Pop domain, as an adeptness towards suiting its audience’s desires.

Sidestepping just for a moment to look at similar artist examples that operate within the genre, we find this process repeated a great number of times through Pop’s many representatives. To hone in on two contrasting examples as reinforcement for this mechanism, we may look towards Calvin Harris and Taylor Swift as illustrations of either gradual or sudden textural change respectively. Debuting his first full-length I Created Disco (2007) into the latter half of the Noughties Pop scene, Harris is notable for morphing each subsequent LP to aesthetically suit the Pop era of its release period. When measuring the ingrained textures of his discography beginnings against those of his latest record – Motion (2014) – we can observe a marked distinction. As an opposing illustration, we may note the viability of a more forceful, sudden change via Swift’s product output, and her divergence into Pop as opposition to her Country roots. Bypassing a need for a lengthy background explanation, Swift begun her musical career firmly confined to the Country genre, actualizing her first four LPs in such a textural manner. Come attempt number five (1989 (2014)) however, Swift publicly denounced any continuation of the classification and vowed to concentrate instead on Pop production – a change that was met will mass scepticism at first. (For convenient examples of each textural reference, I propose an examination of ‘Acceptable in the 80’s’, ‘Open Wide’, (Harris, 2007, 2015), ‘Our Song’ and ‘Style’ (Swift, 2007, 2015) as contrast between old and new). Exuding similar habits to Bieber’s label, Swift’s advocates (hereby expressed by Kelefa Sanneh (2014)) used her case as a springboard for discussion, declaring that ‘Swift has been expanding her musical reach for years now, becoming a bigger presence just about everywhere except on country radio […] But then, no one can say exactly what country music is supposed to sound like in 2014. And so it’s easy to disdain the genre gatekeepers who refuse to make room for a pop star who says she is determined to be led by her musical curiosity’. It pays to note the defiance of the term ‘genre gatekeepers’ as found in this example, as such a phrase that embodies Pop’s penchant for assimilation as previously remarked upon. With it, we again cater to the extensiveness that is evidently achievable within Pop as an indefinable working model that is able diminish our idea of music categorization, to defy any idea of aesthetical segregation in pushing forward an ever-shifting textural foundation for its artists to use as their own success vehicle.

In Harris and Swift, both cases display distinguished similarities to the methodology of latter-day Bieber when it comes to a defining of continued output through the attire of present-day aesthetics; the substantial prolonged success of each Pop participant here insists that we recognize such a routine as one that can largely define Pop prosperity. In wrapping up the investigations of texture shifting and producer-influence in relation to Pop and its respective artists as a result of this analysis, I offer up two conjoined interpretations that may help define the Popstar-producer unity in our understanding of the genre as a wider concept. Firstly, I contend that the definitive role of the producers in today’s Pop are to lend the desirable ‘sonic fingerprints’ to tracks in order to embed the compositions themselves into the present day, ascribing a textural currency to Pop songs as a means of fundamental audience gratification. Consequently, the artist protagonists of Pop can therefore arguably be reduced to the role of a ‘featured timbre’ in any typical instance of Pop production, given that their sold persona is that which lends gravitas to its relative success. As a defining point to this discussion, perhaps it is therefore useful to interpret Pop’s branded ambassadors less so as the musical innovators that are driving forward the omnipresent chart playground, but instead as the many reference points to be utilized by producers in order to convey the flavours and textures that define our present-day society. Speaking as a fledgling music-maker with intent on entering the Pop world, the thought is indeed a reassuring one.

Observations and Conclusions

The 21st century tectonic shift in the status quo of Pop’s manufacturing process has unquestionably thrown up some interesting hypotheses pertaining to how mass-appeal-chart-music is now experienced and wielded by its relative participants – be it Pop’s producers, Stars, audiences or composers. We conclude our discussion once more with this interpretation that the core potential for widespread viability in Pop’s output – as far as its tangible sonic products are concerned – seemingly originates from every place other than the artists’ creative utterances themselves. Our current model of pure Pop allows its protagonists to extract themselves from the entire musical aspect or their career extensively, in order to prioritise and pursue non-musical factors as a means to foster relations with their world. It may well be summarized that the many branded faces of successful Pop now hold office as the third-party middlemen and women of the industry, merely bridging the gap between the behind-the-scenes creators-turned-shapers of its content and the eager beneficiaries in waiting.

As an extension, I suggest a reinforcement of the notion that above all else, lengthened success in the Pop domain is defined almost unanimously by malleability. All subsequent indications point to a conclusion that states that an artist’s receptiveness to the above contention, and therefore their disposition to actively bypass any form of aesthetical classification may well be the defining indicator of their apprehensive longevity. By submitting one’s self to act simply as an envoy to today’s textures, and thereby retaining an openness to shift in self-identity as an artist, Pop acts may place increased trust in this commodification model to bestow unto themselves the reward of social endurance.

If wishing to directly address Pop’s cynics in assessing the ominous consequences that this brave new world may have on our coveted musical values, I would have to argue the following: it seems unfeasible to imagine that this flavour of functionality will plant itself in the other ‘traditional’ genres of our musical world any time soon, at least at such an imposing extent; after all, Pop has evidently found its place in today’s culture by way of its subtly proud disparity from the time-honoured traditions present elsewhere in our many musical relationships. On these grounds, at least, I think it best to allow Pop its own freedom to perform in such a manner, and rely on the assumption that for all its many curiosities, the genre is content with existing under its own independent governance, provided we allow it to do so. Contrasting the negative dismissal of its detractors, Pop presents itself as a model of protest – at least as far as our traditions are concerned; from the extent to which it challenges our idea of linear music construction, to its tenacity to boycott the authentication restrictions that often burden its genre relatives, Pop takes pride in its nonchalance for convention and is all the more successful as a result. Ergo, I wait with baited breath to follow Pop’s definitive nature as it extends into future ground. As for our Star, it may be challenging to predict Bieber’s next step within Pop’s erratic stratosphere, be it a continuation in adhering to Pop’s current textural predilections, or a bid to deviate from its laws entirely. Having made many of the right moves thus far, it’s safe to assume that his acquired fluidity as an artist free from classification will serve as adequate reinforcement in any of Bieber’s future pursuits, and as such, the playground is his.

Bibliography

Grossberg, L. (1992) We Gotta Get Out of This Place: Popular Conservatism and Postmodern Culture. London, Routledge.

Shuker, R. (1994) Understanding Popular Music. London, Routledge.

Joswick, D. (2009) Programme notes in: Bieber, J. (2009) My World. [CD] [s.l.] Island. RBMG. Schoolboy. Teen Island.

Tankel, J.D. (1990) The Practice of Recording Music: Remixing as Recoding. Journal of Communication, 40 (3), pp.34-46.

Frith, S., Zagorski-Thomas, S. eds. (2012) The Art of Record Production: An Introductory Reader for a New Academic Field. Surrey, Ashgate.

Auslander, P. (2006) The Performativity of Performance Documentation. PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art, 28 (3), pp.1-10.

Brown, L.B. (2000) Phonography, rock records, and the ontology of recorded music. Journal of aesthetics and art criticism, 58 (4), pp.361-372.

Moore, A. (2002) Authenticity as authentication. Popular Music, 21 (2), pp.209-223.

Boyd, J. Interviewed by Golden, Z. The FADER (2015) How Justin Bieber Grew Into Himself, According To Poo Bear. [Internet]. Available from: http://www.thefader.com/2015/11/11/justin-bieber-poo-bear-purpose-journals [Accessed: 27th December 2016]

Bieber, J. Interviewed by Clash (2016) Never Too Late: Justin Bieber Interviewed. [Internet]. Available from: http://www.clashmusic.com/features/never-too-late-justin-bieber-interviewed [Accessed: 6th January 2017]

Auslander, P. (1999) Liveness: Performance in a mediatized culture. London, Routledge.

Sanneh, K. The New Yorker (2014) Country Music’s Taylor Swift Problem. [Internet]. Available from: http://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/country-music-shakes-taylor-swift [Accessed 10th January 2017]

Discography

Bieber, J. (2009) My World. [Compact Disc] [s.l.] Island. RBMG. Schoolboy. Teen Island.

Bieber, J. (2010) My World 2.0. [Compact Disc] [s.l.]. Island. RBMG. Schoolboy. Teen Island.

Bieber, J. (2012) Believe. [Compact Disc] [s.l.]. Island. RBMG. Schoolboy.

Bieber, J. (2015) Purpose. [Compact Disc] [s.l.]. Def Jam. RBMG.

Bieber, J. (2011) Under the Mistletoe. [Compact Disc] [s.l.]. Island.

Bieber, J. (2010) My Worlds Acoustic. [Compact Disc] [s.l.] Island. RBMG. Schoolboy. Teen Island.

Bieber, J. (2013) Believe Acoustic. [Compact Disc] [s.l.] Island. RBMG. Schoolboy.

Bieber, J. (2016) Journals. [Compact Disc] [s.l.] Island. RBMG. Schoolboy.

Bieber, J. (2009) One Time. [Online] [s.l.] Island. RBMG. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CHVhwcOg6y8

Bieber, J. (2013) Favorite Girl (Live). [Online] [s.l.] Island. RBMG. Schoolboy. Teen Island. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=myrcMn-C9QI

Bieber, J. (2015) Children. [Online] [s.l.]. Def Jam. RBMG. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nkjwn240AMc

Harris, C. (2007) I Created Disco. [Compact Disc] [s.l.] Columbia. Fly Eye.

Harris, C. (2014) Motion. [Compact Disc] [s.l.] Columbia. Fly Eye.

Swift, T. (2014) 1989. [Compact Disc] [s.l.] Big Machine.

Harris, C. (2007) Acceptable in the 80’s. [Online] [s.l.] Columbia. Fly Eye. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dOV5WXISM24

Harris, C. (2015) Open Wide. [Online] [s.l.] Columbia. Deconstruction. Fly Eye. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zVzhpkFBFP8

Swift, T. (2007) Our Song. [Online] [s.l.] Big Machine. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jb2stN7kH28

Swift, T. (2015) Style. [Online] [s.l.] Republic. Big Machine. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-CmadmM5cOk