Neutral’s contributor base is largely made up of film scholars who are keen to share their passion and dedication to the film industry

MaXXXine

As Disappointing as it Was Anticipated.

By Amber Bissel

Ti West’s MaXXXine (2024) follows Mia Goth’s character, Maxine Minx, as she aspires to become a Hollywood actress after her prior experience in the adult film industry.

Throughout the film, we learn that a serial killer is targeting young women in Los Angeles, the majority of which are connected to Maxine – it becomes evident that she’s being stalked. MaXXXine is the third instalment in West’s horror trilogy. All three films explore characters played by Mia Goth; Pearl (2022) provides a character study in the form of a prequel to the first film in the trilogy, X (2022), as well as being a display of Goth’s unmatchable acting prowess. Throughout this trilogy, West explores themes surrounding violence and pornography, as well as paying homage to a range of film genres. For example, X is a classic-style slasher, akin to that of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1976), and Pearl borrows tropes from other genres, such as the drama, thriller, and even the musical. Much of its mise-en-scene (the overall look and feel of a film) is inspired by The Wizard of Oz (1939). Due to the success of the first two films, MaXXXine has been highly anticipated; it made the most capital on opening weekend out of all three films of the trilogy. Despite the apparent excitement for MaXXXine, at the time of writing it’s the lowest rated out of the three on sites such as IMDb and Letterboxd.

However, the film does have some good points, such as Goth’s incredible performance. Just like in X and Pearl, Goth is able to prove herself as one of the greatest actresses in horror at the moment. From her facial expressions down to her line delivery, Goth is able to convincingly sell whichever character she is playing to the audience. Furthermore, Kevin Bacon and Giancarlo Esposito’s characters and performances were a welcome surprise, actually providing some unexpected comic relief. The film follows on from the events of X, after Maxine escapes the farm. MaXXXine doesn’t neglect the fact that she would be affected by prior events. For example, in one particular scene, she experiences flashbacks to the horror and violence that Pearl and Howard subjected her and her friends to in X, and is clearly haunted by it. Despite this, MaXXXine stands as its own film and doesn’t depend heavily on the first two instalments to tell its story. This is a positive for casual moviegoers, however, it left a lot to the imagination of fans of the prior films. Aside from the few moments mentioned in which Maxine is haunted by Pearl’s actions in X, it doesn’t refer to the story of the other films, or fully wrap the trilogy up in a satisfying way.

Furthermore, the film doesn’t seem to be able to decide how it wants Maxine to come across. There are short moments in the film that portray her as unhinged and when it does so, Goth provides a stellar performance. However, it also conveys her as some sort of damsel in distress, especially within the final act. These two aspects of Maxine’s character seem to be at odds with each other and are unable to create a cohesive study of her character, perhaps damaging the flow of the film/trilogy. Additionally, her character development is hindered by the storyline; it seems to make an attempt at being a character study at the same time as being a crime/mystery/horror film, all of which are unable to be fully explored due to the relatively short length of the film. Consequentially, the quality of storytelling and Maxine’s character cohesion suffers because of this.

The setting of MaXXXine is unmistakeably eighties-themed, demonstrated by the hairstyles, clothing, and even through the use of lighting. West draws inspiration from real-life events and infamous serial killers, most obviously Richard Ramirez, nicknamed the Night Stalker. Ramirez killed thirteen people between the years of 1984 and 1985 in and around California – satanic symbols were often observed at the scenes of his crimes. MaXXXine draws on this for its stalker-serial killer storyline, however, it doesn’t expand upon it. The identity of the killer is unknown for the majority of the film (until the final act), and most of the killings occur offscreen, which feels like a missed opportunity considering the calibre of the murders that were presented in both X and Pearl.

In addition, the final glaring issue presented by MaXXXine is the majority of the third act. After a sequence of unnecessary flashbacks that seem to spoon-feed the audience, Maxine realises that the killer and her stalker is her father, a televangelist who along with the help of members of his ministry, claims to have been creating a snuff film to expose the evil within Hollywood. He ties Maxine to a tree in an attempt to exorcise the evils he believes Hollywood has bestowed upon her. West is clearly attempting a nod towards the satanic-panic present in the 1980s with the religious and cult theming, however, the payoff feels unearned, the killer cartoonish and the motive forced.

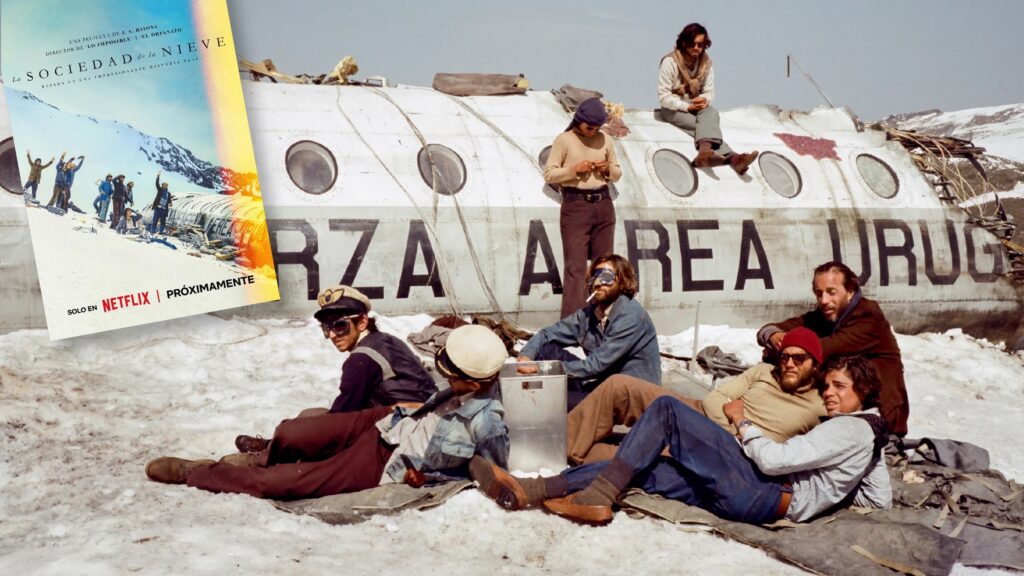

“Who Were We On The Mountain?”

J.A. Bayona’s Society of the Snow (La Sociedad de La Nieve.) (2023)

By Ren Anthony

The ‘Miracle of the Andes’ has fascinated filmmakers and audiences alike since the harrowing true story of human survival became publicly known in 1972.

The story of a plane crash where the survivors resorted to eating their deceased friends for survival has previously been translated to dramatic retellings in film. Frank Marshall’s Alive (1993) and ‘Mexploitation’ film Supervivientes de los Andes! (1976) had earlier attempted to demonstrate the ensuing seventy-two days of gruelling survival. However, it’s Spanish director J.A. Bayona’s La Sociedad de La Nieve, or Society of the Snow (2023), that arguably portrays the ordeal in its most poetic form thus far. By not solely focusing on the horror of the group’s survival, but also the ‘society’ that formed around the goal to escape their situation, Bayona’s narrative takes deep care for the memory of the deceased. The intense cinematography, the mise-en-scene, and the powerful dialogue and performances all coexist in such a way that feels incredibly authentic and respectful towards the victims and survivors alike.

A ten-year-long effort to finance and create the film highlights how crucial it was to Bayona for the dialogue to be in Spanish (specifically Uruguayan), to uphold the authenticity of the story. This allowed the story to be told in the language spoken by the community that was shaped by the disaster. On a global scale, Spanish-spoken media is often overshadowed by English-language productions, which generally have more accessibility to financial backing. Therefore, finding funding to create a more authentic portrayal proved incredibly difficult. Nonetheless, the language of the production is attributed as a large part of the film’s importance, with all of the cast being fairly unknown actors from Uruguay and Argentina. The near-global anonymity of those portraying both the victims and survivors was intended to present the viewer with the opportunity to reflect solely upon the trauma faced by these ordinary, mostly young victims from a more historically faithful position. The intent by the creators to focus on the group as a whole carries in itself the reckoning with mortality, emphasising the power of humanity and grief at odds with nature. These themes can be examined across Bayona’s filmography, most notably in The Impossible (2012) and A Monster Calls (2017), and seemingly harbour a deep narrative fascination.

The experience of watching the film is an incredibly visceral one; the plane crash and avalanche sequences contain graphic body horror, and the idea of cannibalism is included in much of the dialogue – although Bayona was careful to not show much as to not overly-sensationalise the experience. Whilst these themes are upsetting, La Sociedad de la Nieve does not cross the line into commoditising them for the sake of entertainment. The film demonstrates that the deaths of some made the survival of others possible, as their bodies were consumed for sustenance and saved them from starvation. In the same way, it was clarified that the main intention of the film was for the survivors themselves to give something back to those who perished on the mountain – to thank them. Not only does the most recent interpretation of this disaster recognise the survivors, but also shows the audience the help that those who lost their lives gave to those who were ultimately rescued.

The text explores themes of humanity and endurance through suffering with its realism and close camera angles, capturing the claustrophobia of the fuselage the victims were confined to for warmth and shelter. The philosophical relationship between the living and the dead is what touches the spiritual layer that is intrinsic to this retelling’s poeticism. By featuring a voiceover narration from Numa Turcatti, the last victim of the crash to die in the fuselage, the film bridges the metaphysical gap between life and death, and heightens the cohesive idea of ‘society’ across those abandoned in the mountains. The collective power of this group of mostly young men is a theme that is deeply examined in the narrative; every single member was fundamental to the strength of the others. Part of Numa’s intention as the narrator is to elicit an emotional response from the viewer at the unexpectedness of his death. This subverts the hero’s journey narrative arc that disaster films often follow; the ‘hero’ character is expected to survive. This abruptness emphasises the tragedy of how close each of them was to surviving, but how he was no less of a hero for not making it. In the narrative and in the true accounts of the actual survivors, it was Numa’s death that acted as the inciting incident for survivors Nando Parrado and Roberto Canessa to begin their arduous mission to find help beyond the mountain.

The entirety of Canessa and Parrado’s journey is without the previous narration. There is limited dialogue between the pair, and Michael Giacchino’s tense score underlies their scenes. This illuminates their isolation from the rest of the world, but also expresses how close they are to surviving the ordeal with each step.

The film could have ended on the triumphant note of a rescue helicopter arriving, as previous iterations have. However, Society of the Snow opts for a more sobering tone to end on. The closing shot of the film features the surviving sixteen all huddled in the same hospital room, echoing their dynamic in the fuselage. The parallels between the fuselage and the world which they return to emphasises the loss of those who didn’t survive, and the group trauma that stayed with them. Accompanying the shot is a final voiceover from Numa, addressing the survivors, telling them to “keep taking care of each other, and tell everyone what we did on the mountain”. This final line echoes the intentions of Bayona when he set out to create the text a decade prior; he wanted the survivors to be able to give something back to those who died, by telling the world what happened in the Andes in 1972.

Bride of Frankenstein

Sympathy for the Monster

By Hannah Roberts

When faced with the ideology of a monster, typically horror films depict one of two contrasting narratives to the audience.

The monster either devolves from a less-than-fortunate origin, which elicits the audience to understand their contentious actions, or the monster is inherently malicious and possesses the desire to terrorise its victims. Bride of Frankenstein (1935) is the sequel to Frankenstein (1931), and is one of the first iterations of the sympathetic monster in horror. Whale asserts a depth into his characters that transcends their bad actions, recognising humanity in those that would otherwise be labelled as a villain or a monster. The intrigue of The Monster is centred around his human-like nature, but also the uncanny disparity which causes him to be shunned from society and yet elicits sympathy from the audience.

Since The Monster’s conception in the preceding film, he has become aware of his origin as an experiment. This accumulates sympathy because The Monster is made up of body parts from graves and the gallows, including the brain of a criminal. This combination of fragments of those who have already met death causes great wonder in The Monster’s creator, Henry Frankenstein, who wishes to make a scientific breakthrough. However, his ambition likens him to The Monster because he becomes consumed in his experiment to the extent that he doesn’t prepare for the future in which his creation becomes an entity of uncontrollable chaos. Therefore, Henry Frankenstein could also be perceived as monstrous for the lack of responsibility he takes regarding the murders The Monster commits. Although, he is likely exempt from being ridiculed as a monster due to his regret that he created this creature, and his ample attempts to dispose of him. This seems to make him blameless in the eyes of the townspeople, despite being the source of their anguish. Moreover, he is sympathised with by the audience, as he didn’t produce his experiment for a vindictive reason.

A significant contribution to The Monster’s uncontrollable behaviour is the lack of preparation Frankenstein made for his existence, signified by the fact that he was never named and only ever referred to as ‘Monster’. Beyond this, his outward appearance (that The Monster had no capacity to control or change) separates him from societal norms. Therefore, he is antagonised by the townspeople, conditioning him to confront terror and violence by being aggressive himself; he was never taught another way to exist.

Boris Karloff’s performance should be acknowledged as one of the most important factors in generating sympathy for The Monster. He clearly expresses the struggle between the clashing pieces of humanity he possesses, which onlookers perceive as unusual. Karloff also emphasises how The Monster tries to replicate human actions and expressions, but falls too heavily into the uncanny despite his physical humanity – we are forced to sympathise with his futile efforts.

Whale highlights the obstructive effect The Monster’s appearance has on his ability to form human connections in Bride of Frankenstein when he encounters a blind man residing alone in the woods. He is drawn by the sound of a violin, showing his inherent ability to appreciate art. Though he is hesitant at first, The Monster distinctly realises that his appearance is causing his difficulties with others. Whale uses the motif of reflections to convey The Monster’s own disgust when he observes himself in a body of water, allowing him to feel the repulsion he has been conditioned to feel by spectators. Whale utilises the character of the blind man to accentuate that The Monster’s inherent behaviour isn’t the reason he lacks connection; his ‘monstrous’ appearance forces people to react corresponding with their preconceived opinions of him. This barrier is eradicated by the blind man, who doesn’t judge his inability to talk or express himself. In fact, he is able to learn some words and communicate more easily after this encounter, as well as trying alcohol and cigars – things that make him appear human to the audience. Whale elicits our sympathy further when the townsfolk disrupt the meeting between The Monster and the blind man, causing the house to go up in flames. The fire antagonises The Monster and acts as a continuous trigger for him to retaliate and protect himself.

It can be inferred that The Monster’s victimhood stems from the repetitive attacks he preserves himself from that resemble contemporary accounts of lynching. This implies that Whale may have employed The Monster’s constant attacks as a microcosm for racism and prejudice, in that he appears as the ‘other’, who instils fear in those who fit into society. Therefore, he is ostracised and pursued by mobs similar to those who would lynch minorities.

It’s ironic that the titular character of The Bride in Bride of Frankenstein only appears in the final act of the film, as though she is a final resort to change The Monster’s fate and give him a connection. The Monster’s desperation for Henry Frankenstein to create him an equal accentuates his final wish to be understood by a creation akin to him. However, The Bride appears instantly terrified by her existence and the unfamiliarity of being reborn, which in turn causes her to be unsettled by The Monster himself – she declares that she hates him like the rest. It appears that The Bride instantly recognises herself as grotesque and can’t even attempt to live with her monstrosity in the same way The Monster does. This sequence of events encourages the audience to sympathise with The Monster, who can’t even be accepted by a creation that is indistinguishable from him.

It’s clear that Whale wanted to emphasise the tragedy that Frankenstein’s narrative has always portrayed. The Monster is easily able to capture the compassion of the audience because he replicates a child seeing the world for the first time before his untimely abandonment – it’s wonder but mainly it’s terror. Such a message resonates with anyone who is or has felt marginalised in society. The film generates the ultimate sympathy for The Monster because it doesn’t provide a positive resolution for his qualms, due to him not being accepted throughout each attempt he makes at forming a relationship.

Noah Baumbach and Human Relationships

By Isobel Williams

Noah Baumbach’s work as a writer and director often explores the impact of strained relationships on his characters – often tortured artists.

These thematic concerns, his penchant for Naturalism, and consistent collaborations create an intriguing auteur who specialises in the dynamics of relationships.

The history of auteurism resonates with Baumbach’s work. His filmography highlights the importance of art and philosophy through his characters; he almost always includes a character that is an artist of some kind. The thematic concerns of Baumbach’s work reflect a desire to portray more realistic depictions of the difficult aspects of life. Marriage Story (2019) details the impact divorce proceedings have on families, The Meyerowitz Stories (2017) reunites three estranged siblings due to their father’s declining health, and Frances Ha (2012) follows the uncertain life of a woman struggling to maintain friendship and her dancing career. Baumbach often analyses strained relationship dynamics, particularly focussing on families and/or tortured artists. The influence of Naturalism (illusion of reality) on his work is clear; in terms of cinematography, Baumbach tends to use a blend of static wide shots and close-ups to highlight a space that is being inhabited or the key character within the scene. In terms of dialogue, there is a mixture of Naturalism and comedy. Many of Baumbach’s characters have explosive outbursts that represent the irrationality that anger instils in us, and the ridiculousness that comes with it. Yet it is difficult to believe that most people have the same level of wit that his characters possess.

Marriage Story is arguably Baumbach’s most well-known film due to Laura Dern’s Oscar win for Best Supporting Actress, its (more than) 100 additional nominations, and its release straight to Netflix. Baumbach began writing Marriage Story in 2016, using both his and his parents’ divorces as inspiration. Aiming for the most realistic depiction of divorce possible, Baumbach took pains to capture the range of emotions that people often feel during this time. Charlie and Nicole were once in love, and still hold great care for one another and their son, Henry. However, the tension and resentment that is heightened by the divorce leads to an explosive argument, resulting in the pair apologising, holding each other, and sobbing. The external factors of the divorce only serve to make things more difficult, as others’ opinions and self-interests become intertwined in the matter. This is most prevalent in the legal side of the divorce; the lawyers drive a larger wedge between Charlie and Nicole’s already strained relationship. Charlie’s lawyer, Jay, uses gendered assumptions to demean Nicole and accuse her of alcoholism – a stretch from the truth of Charlie’s anecdote. Nicole’s lawyer, Nora, retaliates against his misogyny and arrogance as the hearing becomes a professional competition rather than a legal proceeding. She does this in defence of Nicole due to Charlie’s last-minute switch to a more aggressive lawyer, yet privately she also feeds into the gendered way of thinking, stating that “the idea of a good father was only invented like thirty years ago”. The aggressive nature of the hearing goes entirely against the civil proceeding that Charlie and Nora originally wanted, and through their subtle expressions and infrequent comments, they ultimately must accept that their divorce is out of their control; their relationship will continue to be strained.

The importance of company and relationships is arguably Baumbach’s most integral theme across his filmography; the most interesting of which is illustrated by putting characters through forced togetherness and forced isolation, explored in The Meyerowitz Stories and Frances Ha. In The Meyerowitz Stories, three siblings must reunite and work together to ensure their father receives the best possible healthcare, despite their strained relationships. The tension between Danny and Matthew is evidenced by their competitiveness and jealousy of each other, which is heightened by their father consistently favouring Matthew and underappreciating Danny’s efforts. This all culminates in an argument and physical fight that helps the brothers understand their resentment for each other and their father. Their sister, Jean, has been subjected to serious neglect from their father, causing her to become reserved. Ineffective communication is a major factor as to why the Meyerowitz family’s dynamic is so strained, all of which stems from Harold’s neglectful parenting and stubbornness as both a father and an artist.

In contrast, Frances Ha explores unwanted isolation and loneliness. Frances experiences a tumultuous relationship with her best friend, Sophie, leaving her feeling lonely and depressed. While Frances has several casual friendships, there are several comments throughout the film that suggest that she and Sophie may as well be married. Sophie’s engagement and subsequent move to Japan causes their friendship to break down. Frances begs Sophie to stay in New York, attempting to convince her that she doesn’t truly love her fiancé and that she’d be happier staying with Frances. The theme of the tortured artist is prevalent to Frances Ha; not only does Frances risk losing her strongest relationship, but her career as a dancer is constantly under threat because she doesn’t measure up to the other members of the company – she struggles with both her relationships and her artistic integrity. Baumbach uses various wide shots to illustrate the loneliness Frances experiences. Often there won’t be anyone else in the frame. If there is, they are positioned in the background, not noticing her existence. The cinematography of Frances Ha references French New Wave cinema, mostly from its grey colouring. Perhaps Frances Ha is the clearest example of each of Baumbach’s thematic concerns – the culmination of what makes him an auteur.

As a modern auteur, Baumbach illustrates clear inspiration from older eras of cinema and combines them with his own Naturalistic sense of style, all of which culminates in a series of films that explore the reality and difficulties surrounding relationships. Auteurism is strongly related to art. Baumbach demonstrates this not just through the inclusion of artists, but by making art out of painful, relatable experiences.

A Comparative Analysis of Psycho’s Shower Scene in the Book and Film

By Joe Walker

When Robert Bloch’s 1959 horror novel, Psycho, was adapted for our enjoyment on screen in 1960, Alfred Hitchcock made sure to bring the story to life.

Despite them having the same narrative, there are many differences between the two versions, particularly in the shower scene. Some of these changes were made for practical reasons (such as using music to indicate characters’ internal thoughts instead of being outright told in the book), but some were made to suit a different type of audience. Marion (or Mary in the book) Crane’s death remains arguably one of the most memorable death scenes in cinematic history. Indeed, the scene shocked 1960s audiences, leaving a lasting legacy by opening the door to a myriad of cinematic taboos like nudity and violence. Nevertheless, this scene holds several noteworthy differences from the novel.

Prior to Crane’s murder, Bloch structures his novel to allow the reader to engage with the victim’s emotions and thoughts that arise after she steals $40,000. Crane internally considers how to dispose of her car and the cost of her escape from the legal repercussions of her actions “that would sound reasonable” (37). The reader becomes aware of Crane’s feelings towards motel owner Norman Bates, who she refers to as “that pathetic man”, soliloquising that if she had kissed “the poor old geezer [he] would probably faint” (37). Arguably, this literary technique allows readers to engage with Crane in a way that film viewers can’t. Crane’s internal monologue confirms that she views Bates as weak and peculiar, thereby creating a false illusion that there is no danger. Hitchcock’s portrayal differs; Bates secretly watches Crane and harbours sinister motives. The scene contains no dialogue and is instead superseded by brief moments of silence before dramatic music resonates, building suspense before the violence unfolds. Consequently, both versions highlight the semantic field of horror and suspense, via soliloquy in the novel and music in the film to engage readers and viewers respectively.

Both Bloch and Hitchcock convey the theme of suspense in different ways to engage readers and audiences, despite portraying the same scene. Bloch’s literary devices, like the use of Crane’s soliloquy, create a conversational yet unnerving tone married with sharp staccato sentences to heighten the tension and invite readers into Crane’s mind, such as “Mary stood up.” and “She’d do it.” (37). This technique is less obvious in Hitchcock’s portrayal; instead of dialogue, silence creates an unnerving atmosphere. The film adaptation also makes use of simple cinematography and slow camera movements, allowing audiences to embody the false sense of security felt by Crane prior to her slaughter. Although the dialogue of the narrative is absent, Hitchcock utilises facial expressions representing Crane’s inner torment, thus compensating for the lack of vocabulary. Hitchcock thereby foresees themes of voyeurism and scopophilia (taking pleasure in watching someone without them knowing) when Bates watches Crane through the hole in the wall. Both instances showcase how suspense can be presented both visually and in a literary format to present the same scene though they are outwardly different.

Crane’s murder in the novel differs from Hitchcock’s portrayal in the film in myriad ways. Bloch’s portrayal is described with less detail, commanding a few mere sentences before ending abruptly. This format mirrors the literary format utilised throughout the scene with the use of short sentences. The sexual undertones in Bloch’s portrayal compensate for the lacking details, for example through the use of white imagery; he implies that after her shower, Crane will “come clean as snow” (38). Traditionally an orthodox view of white is synonymous with virginity and purity, a trait mirroring Crane’s forename which she coincidentally shares with the mother of Christ. Likewise, Crane’s provocative movements symbolise an awareness of her growth into womanhood. Bloch states that “If she’d been a religious girl, she would have prayed” (37), representing how she is becoming supercilious, believing she will get away with her crime and increasing sexuality. Her over-confidence is also proved by her thoughts about herself. Whilst she looks at herself in the mirror, she thinks she has “a damned good figure” and demonstrates “an amateurish bump and grind, tossing her image a kiss”, insinuating her growing self-confidence and sexuality (38). As she giggles to herself numerous times, she implies a lasting immaturity within her. However, moments after this series of self-empowering thoughts, she meets her gruesome death. Crane’s death arguably harbours hellish connotations, as “the room [begins] to steam up”, symbolising her fate for both her provocative and thieving conduct.

Hitchcock’s version of Crane’s murder is more grotesque and visually disturbing. Although the murder in the novel commands a few vague sentences, Crane’s death in the film remains at the forefront of audiences’ imaginations due to the drawn-out graphic content for shock value. Hitchcock steers away from Bloch’s sexually transparent narrative, thus granting focus on the suspense, violence, and horror. However, the film retains minor provocative elements, such as close-ups of Crane’s legs upon entering the shower and her looking titillated when the hot water from the shower gushes over her body. For the most part, however, these aspects from the novel are overshadowed within the film, as the viewers are ominously and eagerly waiting for something unfavourable to occur. The use of simplistic cinematography is contrasted against the white backdrop of the bathroom, which is eventually darkened by Bates’ arrival, demonstrating how white is used to make the darkness of his shadow and the blood of Crane stand out. Hitchcock’s portrayal presents good versus evil and the insanity of the human mind, while Bloch’s literary portrayal focuses on the sexual motives underpinning Crane’s murder, despite both examples detailing the same scene.