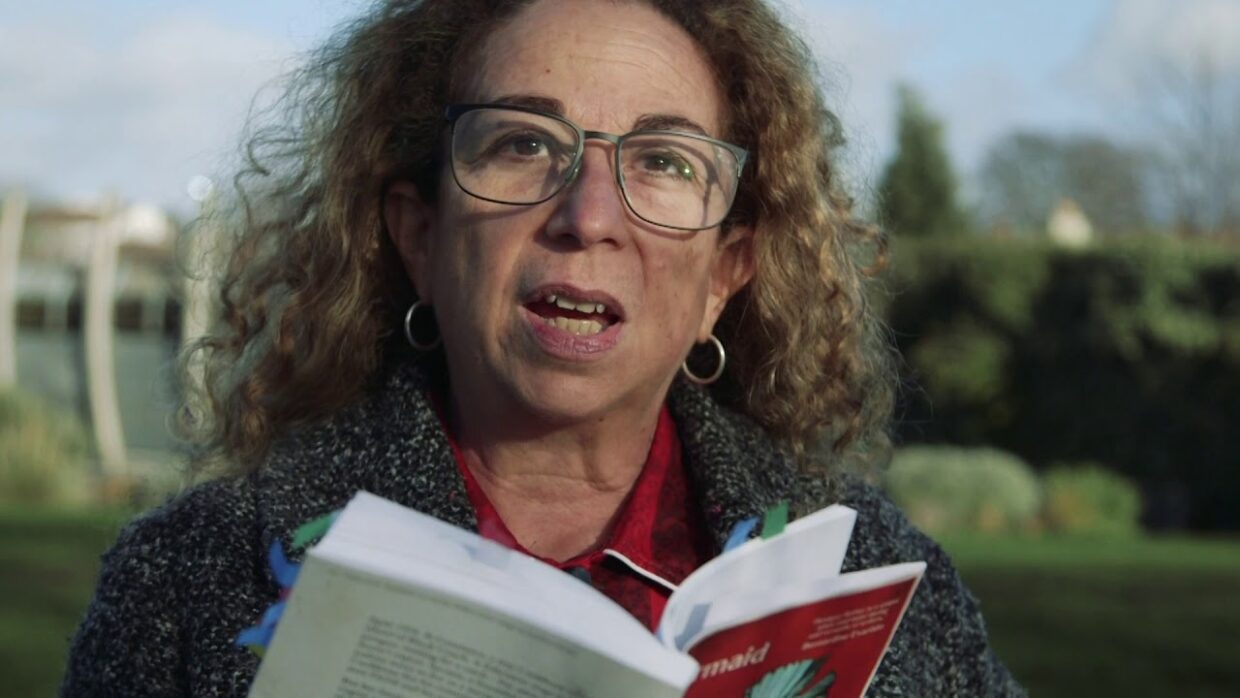

On Saturday 6th March, I participated in a literary event, where multi award winning author, Monique Roffey, was interviewed by Dr Emily Zobel Marshall. This was a Leeds Lit Fest event, organised in partnership with The Carriageworks Theatre.

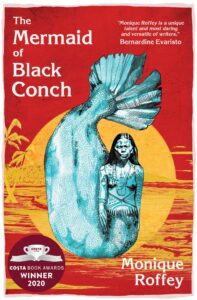

Monique Roffey was born in Trinidad but mostly educated in the UK. She is a writer of novels, essays, poems and a memoir, and Senior Lecturer at Manchester Metropolitan University. Roffey has recently published her seventh book, The Mermaid of Black Conch (Peepal Tree Press), which won the Costa Book of the Year 2020.

The emergence of her career:

Roffey shared that there was a specific moment in which she decided to write fiction, in her mid thirties. However, she has always been interested in writing. As a child, Roffey would graffiti her home, denying it was her.

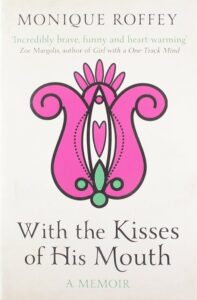

Her memoir:

Roffey’s memoir traces her personal journey of sexual self-discovery. Although this memoir is almost ten years old, Roffey still receives responses as though it was published yesterday. She is proud that it has had a positive impact on both men and women. One man told her, via Facebook, that he got married as a result of reading the book. Conversely, Camilla Long of the Sunday Times expressed her hatred of the book to 1.6 million readers. Accepting these mixed responses, Roffey says that she even makes herself “blush and flinch”.

Folklore:

In her writing, Roffey draws upon western fairytales, as well as African folklore. However, she questions whether African folklore belongs to her. As a European-Caribbean writer, Roffey is unsure what her lore is. Creole is a large part of the cross-cultural fusion of her narratives. Roffey explains that she slips into creole in her head, as her friends and family speak it. She feels it’s impossible to write a Caribbean novel without that language.

Feminism:

While Roffey understands why feminism is fractured, she believes that we should eliminate competition about injustice. She explains that intersectionality within feminism is a good thing, as it proves that people want to come together. “No one is free until we’re all free”, she says. This is why she advocates intersectional feminism in her writing, featuring ‘othered’ women, feared by their patriarchal society.

Speaking particularly of her home region, she emphasises that women are consistently going missing and being murdered. She feels that outsiders often reduce the Caribbean culture to a place that’s lovely and hot and full of nice people. Roffey feels strongly that this false fairy tale image overlooks the dangerous misogynistic culture. Thus, in The Mermaid of Black Conch, she incorporates uncomfortable scenes of her female protagonist being dragged, and urinated on, by dominating men.

Roffey emphasises that the first stories ever told were female centric, but we somehow lost touch with the goddess. Our stories have become focussed on the male hunt, drama and catching the warrior. In this sense, Roffey’s writing is nonconformist.

Racial tensions:

Roffey is invested in enquiry around her racial background and history, which remains unresolved. She emphasises that the injustices and events of the past are present in the language, architecture, landscape, people’s thoughts and speech, in a visceral way. However, she worries that people in the UK aren’t familiar with colonialism – colonial history may be touched upon in schools, for example, through black history month, but not explicitly taught. As part of a “tiny canon” of Caribbean writers with European background, Roffey explores complex racial politics and tensions within her writing. Roffey is braver in discussing race in her most recent book – “I’ve come a long way”, she says.

Mermaids:

Humanity has dreamt up the mermaid, as a powerful, strong goddess, existing everywhere, explains Roffey. The Mermaid of Black Conch tells the story of a mermaid trying to make a life for herself as a woman. Roffey explains that the goddesses of her writing come to her in dreams, wanting to be part of what she does.

In 2013, in the north of Tobago, Roffey witnessed people kayaking and a fishing competition. She remembers “getting the creeps” seeing a big fish hung up. The weather was stormy. There was also a suicide. She claims that the spirits were restless that week, and that is when the mermaid came to her in her dream.

Dr Emily Zobel Marshall shares that the mermaid was present in her dreams, after reading the book. She also recalls looking down at her feet while in the bath and imagining a tail, putting this down to Roffey’s intricate imagery.

Evaristo:

At the mention of Bernardine Evaristo, Roffey claims that she is one of the greatest – a role model for us all. She applauds her for being a writer who has taken her community along with her. Evaristo is committed to using and sharing her platform. Roffey says that we always knew this was important, but more so now.

Publishing The Mermaid of Black Conch:

Dr Emily Zobel Marshall highlights that although The Mermaid of Black Conch has been “wildly successful”, and awarded established literary prizes, the book was initially rejected by large publishing houses. Roffey acknowledges that many writers have been through this, and explains her understanding of the situation. She states that although she has a canon of books, and has been writing for a long time, sales figures are important to publishers. She elaborates, describing herself as a “complicated package”, beyond the comprehension of many publishers. Despite their initial fear, Roffey feels that publishers are coming to accept her, due to acknowledgement from other writers, particularly Caribbean writers.

When Jeremy Poynting (Peepal Tree Press) wanted to publish her book, Roffey was delighted. Peepal Tree Press, a Leeds-based publishing house, is one of the biggest publishers of Caribbean literature. Roffey insists there are few people in the world who can edit Creole, so she knew that her book was in the right place.

Crowdfunding:

As a unique method of financing her publicity campaign for The Mermaid of Black Conch, Roffey turned to Crowdfunding. She acknowledges that no author had previously done so, but claims that it’s not as bad as writing a book about her sex life, so “Why the fuck not?”. She also mentioned that some fellow authors advised against it and said it was weird. Despite this, Roffey maintains that she “didn’t care enough”. The Arts Council, and her publishers were supportive of her decision. Raising £3,000 in a week, the campaign was successful. Roffey said it was an easy process, which she recommends. She enforces that, “It’s not humiliating, there’s nothing to be ashamed of”, and advises authors to be active and get into it – “You’ll surprise yourself.”.

This is what Roffey’s crowdfunding page looked like, with details of her book, and rewards offered in return for donations.

Why is your book admired by readers?

Dr Emily Zobel Marshall notes that The Mermaid of Black Conch has received huge fascination over recent months, and asks why this might be. Roffey thinks the world is ready for some “argie bargie”. She also feels that her growth as an author has aided the reception of the book, stating that ten years ago, she wouldn’t have dared to write this book.

How are Trinidadian writers being developed?

The internet has enabled the biggest changes in giving marginalised voices and writers a “space and a leg up”. Literary festivals, such as the Bocas Lit Fest in Trinidad and Tobago, and Calabash in Jamaica, have also had an impact. Roffey says that the people involved with these festivals have encouraged meetings and workshops, alongside the emergence of female voices – there is now tonnes of energy out there. Roffey herself has taught and ran retreats for Caribbean writers. Roffey’s friends and students are also gaining exposure through BAME scholarships and university attendance.

“My career isn’t just about me and my books.”

Roffey, In conclusion

To be a writer, when you come from a place without provision, you have to be an activist. Many Caribbean writers are focusing their energies on being politically committed, as well as aesthetically committed. Roffey enforces, to be a Caribbean writer, is to be an activist too.

Written by Cassie Harrison.

For more from the Leeds Lit Fest, see reflections of an event featuring Saima Mir or a panel about writing the landscape.