When one of my university tutors mentioned that Jessica Andrews would be in York as part of the York Literary Festival, I was immediately excited at the prospect of hearing her discuss her career and life. Though this quickly turned to disappointment as I found I had prior commitments on the night she would be on stage.

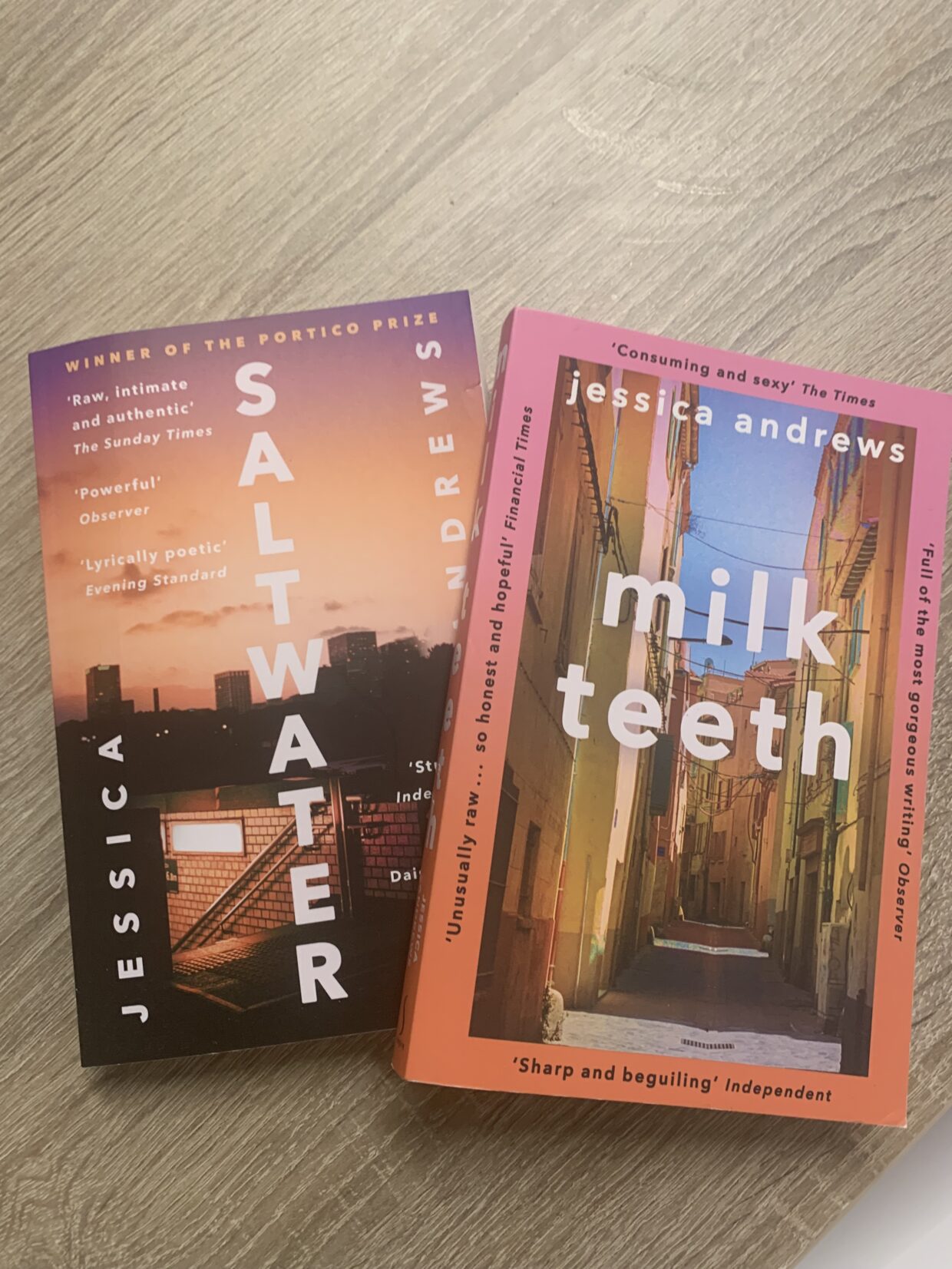

Eighteen months prior I had fallen in love with her novel Saltwater. I have always been a lover of poetry, and though Saltwater is poetic in so many ways, upon reading I felt a sense of awakening to what’s possible in my own writing. If you haven’t read Saltwater, I can’t recommend highly enough doing so at your earliest convenience.

On the face of it, Saltwater is the story of someone trying to find themselves by delving into their family’s history. A story about the relationship between mother and daughter. A story about coming of age in the transition from childhood to adulthood.

Although, Saltwater was so much more than that for me. Due to the episodic nature where events are told through a short, paragraphed structure, each sentence feels nourishing and crafted. Each page had me turning to the next to see what genius description Andrews was going to hit me over the head with next.

So, in short, read Saltwater. It’s great.

But the point of this isn’t to review Saltwater. As I was saying, I found myself more than disappointed at missing her talk about her work. When my tutor heard me discussing it with my friends, he smiled and said:

“Would you like to meet her?”

He was almost laughing as he said it. I smirked and shrugged, thinking he was joking. It turns out he had ways of making it happen. So, when it was framed to me as a chance to conduct an interview with her for Whereideasgrow, I jumped at the chance.

When initial contact was made, I wasn’t sure what to expect. Whether it was asking her a few questions via email, or a five-minute conversation either side of her talk, anything would have been great. When she asked me if I would like to meet her for coffee an hour before her event, I couldn’t believe it.

So here I am, sat in one of my favourite coffee spots in York on a murky Saturday afternoon. I’m nervous for some reason. I think it’s hitting me just how much I love Saltwater. Not only that, but her new novel Milk Teeth too. As a writer myself, I feel a little intimidated. I see a woman who looks like her peering around the coffee shop, I realise despite our communication she doesn’t know what I look like. I go up to the counter and introduce myself. She insists on buying me a coffee and herself a pot of tea. I can tell already this is going to be a nice time.

Our conversation quickly moves from what I thought it was going to be. It’s not formal, it’s not rushed by the time constraints. It’s natural and mutual. We discuss how her process for writing Saltwater was one of trial and error and endless post-it notes, searching for a structure and a voice. It inspires me to know that a novel that had such a profound effect on me was not smooth sailing. I ask her how she feels about the comparisons it has gathered. As if reading my mind, she mentions Sally Rooney’s Normal People, where a comparison lies in a review on the back cover of Saltwater. Jessica is quick to note how flattered she is, as all writers would be. My friends will tell you how much I love that book. However, we both simultaneously agree that we do not see that comparison and how different they feel from one another. Jessica speaks of how she wanted to craft something with a voice of her own, so she is indifferent to comparisons of other authors.

Jessica then asks me about my own writing. I tell her how I have self-published a novel and a collection of poetry. I explain how I feel writing about my disability is important to me and how I feel disabled voices are underrepresented. She agrees and is interested in learning about my writing. I explain that when I write, I write for me. I tell her how I have only started the traditional publishing journey now, because I don’t write to get published. I write because it’s how I express myself, and that it’s a way for my friends and family to enjoy a physical copy. What I appreciate is that it’s not a fake, forced interest. She wants to engage in learning about my experiences. We go on to discuss my time as a Creative Writing student at York St. John over the past five years. We compare it to her experience as a lecturer part time in London. We concur that attitudes towards different styles are noticeable and how this could be down to a range of factors, from varying ages to cultures and backgrounds to the class of the numerous students.

I’m astonished that what I thought was a five-minute interview is moving towards an hour-long conversation. I’m not sure why, it seems like the most natural conversation I’ve had in a long time. It moves from the play she’s adapting in Newcastle, to my love of St James’ Park to the quality of fish and chips you get on the North East coastlines. As time moves towards the reason Andrews is in York in the first place, I ask her to sign my copy of Milk Teeth, for I left Saltwater at home on today of all days.

Typical Elliott.

She does so graciously and we say our goodbyes. Once she leaves, I study the message she’s left on the title page. It hits me how enjoyable the experience was, not just from a writing perspective but on a human level too. It’s one I will cherish for long time and will keep a keen eye on Jessica’s future projects.

Here are the questions I was fortunate enough to ask Jessica:

What is one piece of advice you’d give to a new writer trying to navigate the publishing industry?

I think that feeling excited by your own work is the most important thing. The publishing industry can be complex and overwhelming and I think you really need to be in it for the work itself: that should always be the thing you care about most. I also think it’s a balance of learning when to stick to your guns and when to listen to advice: there is a lot to learn, but it’s important that the way in which your work is marketed feels authentic to you.

Do you think it’s important to hear diverse voices and if so why?

Historically, novels were published by a small, elite group of people, and the stories they told weren’t representative of different kinds of lives. Representation is important because it gives you permission to dream, and allows you to feel that your life is meaningful and important: everyone is entitled to that. There is a big push for diversity in publishing, which is great to see, but systemic inequality begins in (and maybe even before) childhood. We need a radical re-imagining of our education and class systems, in order for published work to become truly diverse and representative.

What advice would you give to someone at the beginning of the process of writing a long project?

Keep going! I find it useful to call a piece of writing a ‘project’ as opposed to a ‘novel’ in the beginning, as it feels less intimidating. I think the biggest obstacle to completing a long project is self-doubt and self-criticism, and it’s important to be aware of that, and try not to let it take over. It can be helpful to keep writing without too much editing or reading back until you have a substantial amount of words. It’s also useful to go to readings, or to send your work to trusted friends, to create a sense of community, as writing can be very solitary. I often create a visual moodboard that evokes the tone and feeling of my novel, to help me begin to visualise it.

Why do you write? And why do you tell the stories you do?

Writing is my way of making sense of the world. I usually write from a sticky knot of questions or emotions that I don’t fully understand. It is a way of slowing things down and looking at them from different angles. It also feels important to record the stories of people and places that aren’t often written down, to stop them from slipping away.

Elliott Scriven