5 Days of Open Education – Day 1: What is Open Education and why is it important?

| Activity | Time Required (approx) |

| Blog post | 20 (including video) |

| Activity | 10 |

What do we mean by Open Education?

At its core, Open Education is about removing barriers to Education. It is a movement benefiting from the potential for technology and new media to enable cheaper and more widespread access to educational resources and outputs.

Open Education encompasses resources, tools and practices that are free of legal, financial and technical barriers and can be fully used, shared and adapted in the digital environment. (SPARC, ‘Open Education’, last accessed 24/02/2016)

The global Open Education movement has risen to prominence in Higher Education in the last decade or so with an increase in policy, strategy and programmes dedicated to opening up content and making it freely available, where ‘content’ might be teaching resources, data, software, research publications etc. This coincides with developments in the field of licensing – notably, Creative Commons licensing – that allow for more widely understood mechanisms for legally sharing, adapating and reusing free content.

In Open Education, for a resource to be fully open, it is generally accepted that it must be both ‘gratis’ (zero cost, no barriers to access) and ‘libre’ (no barriers to reuse). You must be able to access the resource free of charge and have the legal rights to reuse, revise, remix and redistribute the resource and/or adaptations of the resource. In other words, Wiley’s 5 ‘R’s of Open should be easily and legally achievable.

In Open Education, for a resource to be fully open, it is generally accepted that it must be both ‘gratis’ (zero cost, no barriers to access) and ‘libre’ (no barriers to reuse). You must be able to access the resource free of charge and have the legal rights to reuse, revise, remix and redistribute the resource and/or adaptations of the resource. In other words, Wiley’s 5 ‘R’s of Open should be easily and legally achievable.

Open Education refers to more than just opening up access to content however. In his oft-cited Tedx talk, David Wiley proffers that while the nouns may differ – open content, software, research, policies etc. – the action and principle remains the same; it is fundamentally about sharing. It’s based on the premise that Education cannot exist without openness since it is inherently an enterprise of giving or sharing (of knowledge). Watch Wiley’s talk below for an introduction to the principles of Open Education and its place in our future:

David Wiley, TEdxNYD, Open Education and the Future, June 2010.

So, when speaking of Open Education and Open Education Principles, advocates speak of a wider movement and cultural shift towards greater collaboration, equality and a community of sharing. With the advent of new media and platforms we also have the means to share, and thus educate, like never before.

Arguments for…

The most obvious benefit of Open Education is that it opens up information and knowledge to those who might not have had the means to access educational opportunities. Making educational materials openly available for others to share, reuse and remix can reduce the cost, language and format barriers to learning. The most publicised example of freeing content and opening up access to online higher education has been the rise of the Massive Open Online Course (MOOC). Recent years has seen a proliferation of universities and individuals developing short, free, large-enrolment courses across different languages, some of which are available for others to reuse, adapt and re-run in their own context.

Within formal education, tutors can also reduce resource costs for students by developing modules around pre-existing or self-developed open resources and open textbooks. According to Creative Commons’ 2015 State of the Commons Report, open textbooks have saved students $174m to date, with $53m more projected savings in the 2015/16 academic year. Openly available materials allow students to explore a subject before enrolling or arriving in the classroom, and can also allow learners to develop their own informal means of study support, provided they are supported to develop their critical skills for evaluating resources.

There are benefits for the educator, researcher and educational institution too.

- Studies confirm that making research openly available online rather than behind a publisher paywall, results in a higher citation impact for that research. Hajjem, Harnad & Gingras’ (2005) cross-disciplinary comparison of 1,307,038 articles concluded that open access articles have a higher citation impact of between 36%-172%. If you’d like to know more about the Open Access Citation Advantage, SPARC Europe maintain a list of relevant studies.

- Making your outputs and your processes open for scrutiny and collaboration facilitates continuous quality assurance. Contributing to a community of open educators for review and comment means you have a free, virtual pool of peer observers or reviewers with whom you can adapt and improve your work.

- A follow-on from this are the opportunities for collaboration and career development that can result from opening up your work. The more available your work and your name, the greater the possibility of making meaningful connections and attracting invitations for conference talks, or teaching and research projects.

Those are all arguments for contributing to the Open Education community, but what about the benefits as a recipient in the Open Education? Even if you don’t make your own resources freely available, no doubt you have evaluated others’ when researching a topic, or designing a lecture or resource. Has this helped you to improve your own work? Reassured you that you were on the right track? Have you used freely available and editable software as part of your work (hint! Moodle and Mahara are open source software!)? Have you directed students to freely available resources online, saving you the time and effort of reproducing them yourself? There! You’ve already benefited from Open Education!

Some Challenges…

The picture isn’t all rosy, of course. There are challenges around sustainability, particularly in the area of Open Educational Resources (more on these tomorrow), where projects receive initial funding to develop resources but sustaining those resources is underfunded. Are they left to become outdated, links broken, formatting incompatible etc.? Or more problematic, what happens when support for entire resource repositories is withdrawn, as has happened with one of the UK’s largest OER repositories, JORUM.

The issue of quality assurance is a double-edged sword. Whilst the Open Education community can itself contribute to quality improvement by reusing, adapting and building upon existing work, there is not always an overall editor or final gatekeeper for freely available material. Who provides final assurances on quality or accuracy? It’s important to note here that this is not always the case. For example, most Open Access research journals adhere to the same rigorous editorial and peer review processes as traditional, subscription-based journals.

You might well be wondering where intellectual property rights fits in with all of this sharing and openness? Well we’ll look at licensing openly available work on Day 3, but you’re right: understanding and protecting your rights and the rights of other educators can be an initial barrier to people making and reusing open educational resources, and to publishing open access research.

Reusing an open/free educational resource does not necessarily mean a cost-saving for the user when the hidden costs of reuse are considered. For example, in reusing OERs the cost of one’s time and possibly software to adapt, update or localise a resource should be weighed against using paid-for content or creating a replacement resource from scratch.

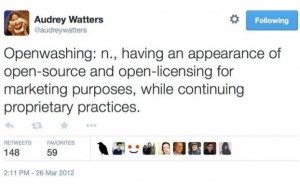

Finally, there’s a challenge of misappropriated terminology and debates about degrees of openness. Cable Green (Director of Open Education at Creative Commons), speaking at last year’s OER15 Conference (Cardiff), drew interesting comparisons between ‘Greenwashing‘ in the environmental sector and the rising number of organisations, companies, individuals etc. promoting a course or resource as ‘open’ for marketing purposes when, in reality, it doesn’t meet the criteria of an OER. Highlighting Audrey Watters’ definition of ‘Openwashing’ (see tweet), he cited Udacity’s Open Education Alliance which has drawn criticism for being ‘open’ only insofar as users can view materials freely, but restrictive licenses mean remixing and redistributing the materials is forbidden. Similar criticisms are emerging in the field of open badges, where commentators like Doug Belshaw are criticising educational companies such as Pearson for co-opting popular open education initiatives for commercial gain.

Finally, there’s a challenge of misappropriated terminology and debates about degrees of openness. Cable Green (Director of Open Education at Creative Commons), speaking at last year’s OER15 Conference (Cardiff), drew interesting comparisons between ‘Greenwashing‘ in the environmental sector and the rising number of organisations, companies, individuals etc. promoting a course or resource as ‘open’ for marketing purposes when, in reality, it doesn’t meet the criteria of an OER. Highlighting Audrey Watters’ definition of ‘Openwashing’ (see tweet), he cited Udacity’s Open Education Alliance which has drawn criticism for being ‘open’ only insofar as users can view materials freely, but restrictive licenses mean remixing and redistributing the materials is forbidden. Similar criticisms are emerging in the field of open badges, where commentators like Doug Belshaw are criticising educational companies such as Pearson for co-opting popular open education initiatives for commercial gain.

Reference resources…

This week, we are introducing specific aspects of a very vast field. Each of these topics could be a five day (or week!) course in their own right, so they are by no means exhaustive. The intention is to introduce you to the key points as a jumping off point for further reading or discussion, wherever you are interested. We’ll point you towards reference resources which you can bookmark and return to if you want a more comprehensive picture in the future.

The Paris OER Declaration: The 2012 Paris OER Declaration was formally adopted at the 2012 UNESCO World Open Educational Resources (OER) Congress and was a significant milestone in the Open Education movement. It calls on governments worldwide to openly license publicly funded educational materials for public use.

The Open Education Handbook: This is ‘living’ open textbook whose contributions were crowdsourced by interested parties and expert working groups, co-ordinated by the Open Knowledge Foundation. It is a vast reference source for information on definitions, key issues, useful tools and software, case studies and real-life examples. It’s well-structured, comprehensive and signposts to additional material on many elements of the Open Education ecosystem, e.g. Open Data, OER, Open Licensing, Open Communities etc.

The Open Education Consortium: A global network of institutions, organisations and individuals – and coordinators of this week’s Open Education Week – dedicated to furthering awareness and adoption of Open Education practices and principles worldwide. Their Open Education Information Center is a one-stop-shop InfoKit on all aspects of Open Education. Resources are usefully divided by target reader groups of faculty, students and administrators. The Impact of Openness on Institutions interviews with university leaders are also an interesting read.

SPARC: SPARC (The Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition) advocate for policy (largely in North America) and coordinate projects, research, events and resources to facilitate open sharing of research outputs and educational materials. Their aim is to “democratize access to knowledge, accelerate discovery, and increase the return on our investment in research and education”. SPARC are particularly active in topics related to open research (open access publishing, open data etc.) and their Popular Resources page is a useful starting point on their site.

Activity

We mentioned above that degrees or a spectrum of openness are often discussed in relation to Open Education. In the comments section below, describe what you believe Open Education means in your context and what experience you have of engaging with the Open Education agenda to date.

We advise a minimum of approximately 50 words and max of 200.

Complete at least three activities across the five days to earn our ‘Open Education Enthusiast’ badge.

Still to come…

- Day 2: The what, why and where of Open Educational Resources (OERs)

- Day 3: Creative Commons Licensing: know your SA from your ND!

- Day 4: Introduction to Open Access Publishing

- Day 5: Becoming an Open Educational Practitioner

Don’t forget to follow us on Twitter at @YSJTEL and @YSJ_ILS or search the hashtags #YSJOpenEd and #OpenEdWeek for additional materials or comment.

Róisin Cassidy (Technology Enhanced Learning),

Ruth MacMullen, Ruth Mardall and Clare McCluskey-Dean (Information Learning Services)

Working in the disability sector, Open Education means that it is easier to adapt documents for disabled students. Too often it takes a long time to obtain books from publishers to adapt them into the format compatible with the individual’s need. Open Education also means getting access to the latest research in the disability sector, allowing people like me to provide a better support to disabled people.

Working within the disability sector Open Education means everything is accessible to everyone studying whether they have a disability or not and this should not incur a cost to them and there should be no barriers. For example visually impaired students will be able to access and read the same documents as everyone else on their course without being disadvantaged because of their disability.

Elizabeth, I’m curious if you’ve found that websites have improved their accessibility over time.. Do you have any tools for evaluating website accessibility? I used to use Bobby before it was sold to IBM and now is a subscription-based tool.

As I don’t have a context at YSJU to utilise for this, I’ll draw on my recent middle school ICT teaching where I’ll cite three examples of Open Education. With the teaching staff at the school, I promoted the use of Edmodo*, a freely-provided and hosted OER Learning Management System that proved to be highly appropriate and effective for middle school teachers, students, parents and even admins! As a teacher, on this platform I created and delivered four Digital Citizenship courses, one for each grade level in the school using material from another OER – Common Sense Media**. As part of those courses, I helped students’ understanding issues associated with copyright vs Creative Commons***. I believe that through modelling the uses, practices and philosophies of Open Education Resources, plus providing opportunities to explore the implications of using OERs, future generations will see that there is a valuable alternative to the proprietary, licensed, copyrighted world that those in my generation grew up with and the assumptions that it carries.

* edmodo.com

** commonsensemedia.org/educators

*** creativecommons.org

Working within ITE within academia, Open Education for me refers to both research and resources. It is important that the research which is completed is available for everyone, whether they be other academics, students or even practitioners. It is important that this research is not kept behind ‘closed journals’ with payment being required in order to access it. I also think that resources should be completely open as well. With the creative commons license in place, these could be used to benefit all the learners and practitioners, rather than putting a price on them.

I am also very interested in the accessibility which was previously mentioned within the replies. It had not necessarily occurred to me to think of Open Education in this form – thanks for highlighting this for me.

Hi Ian, this is really interesting. You may like this webinar on accessible OER, on tomorrow:

https://www.alt.ac.uk/about-alt/special-interest-and-members-groups/open-education-sig

I’ve only recently started to think about the accessibility potential of OER too, and how good design often goes hand-in-hand with core accessibility principles. For example documents – logical structure, headings, tabbed navigation, alt tags mean they are accessible to screenreaders, but also easier to reformat and reuse. Another example is subtitles – they benefit people who cannot hear, but they also help those who can’t use the sound for technical or situational reasons, or who are watching a video in their second or third language.

Open Education to me is a fantastic opportunity to build a broad network of educational resources. Many of the things that Wiley discussed in his lecture resonated with me in terms of my experience with Open Education so far. Prior to joining YSJU, I was involved in developing and providing access to sets of resources to educate students about library services. Moodle was used to facilitate this and whilst I believe that Moodle is a useful platform, the nature of password protecting access seemed to conflict with its intended open nature. There was no way to grant access to the wider community who may have gained from resources. In addition to this, changes from auto- to self-enrolment to courses provided a further barrier to learning as students had to jump an additional hurdle and choose to enrol on the course to access content in the first place. Induction sessions were implemented with the opportunity to enrol on courses – this worked well however, this also felt counter-intuitive in terms of taking away student choice.

The principles and practices of open education raise a series of interesting questions for the HE sector in particular. It will be interesting to explore how the development of open education impacts upon other pedagogical changes in the sector such as blended learning and the flipped classroom. In the context of Media Studies, students seem increasingly to engage with learning via the use of their smart phone devices to access content, conduct research and link to the University web-pages and email. At the same time students have expressed via mechanisms such as mid-module feedback and in-class discussion that they enjoy the social (face-to-face and co-present aspects of aspect of learning). Therefore it will be interesting to see how developments such as open learning attempt to bring together the social (co-present) aspects of teaching with on-line platforms, learning resources and forums. Another key question is the economic model that will be used to sustain open education. For instance, how will Higher Education Institutions provide the funding for these types of learning and teaching? I recently came across the FutureLearn platform which contains many open source lectures and learning sessions which can be transferred into learning certificates. However, what was unclear what how FutureLearn is funded. Would YSJ consider contributing to FutureLearn or develop something similar?