If I’m completely honest and not particularly worried about my diminishing levels of credibility, I’ll admit that my first musical hero was an unusual one. I would love to say that it was Norman Blake or Kristin Hersh. If I was doing that reverse hipster thing, I might even say it was Kylie. But no, it was Michael Winslow from the Police Academy films.

I wasn’t really supposed to watch these as they were, according to my mum, ‘a wee bit rude’ and, according to my dad, ‘a waste of time, money and our video shop card’. But watch them I did. I watched them at mates’ houses, at the cinema when I was a bit older and even on our treasured video machine when I had temporary control of the card. They are of course deeply problematic films. They are riddled with cheap misogyny, crass homophobia, racist stereotypes and the kind of cheesy celebrations of Technicolor capitalism so often at the heart of 80s Hollywood. I suppose they are anti-authority in the same way Smoky and the Bandit and Cannonball Run are and they do have awesome car chases and explosions. When you are an eleven-year old, this is usually enough.

But – and it is a big but – they featured the magical mouth of Michael Winslow. As a kid, he grew up on an air base and battled his loneliness by impersonating aircraft and vehicles. His mouth became a conduit for the sonic world that he inhabited. So, after an early career on TV and in Cheech and Chong (now THAT’S a problematic film, let’s come back to that in another blog post), Winslow played Sgt Larvelle Jones in every iteration of the Police Academy franchise (way better than that part-timer Steve Guttenburg). One of the good guys, his role in the films was to provide noises that usually served one of two purposes. One: he made noises that added to the party. If there wasn’t a boom box available then Jones would provide the tunes (his version of ‘Purple Haze’ was literally the first time I heard Jimi Hendrix). Two: he made noises that hoodwinked the criminals and embarrassed the corrupt top brass Harris and Proctor. He impersonated CB radio, submarines, semi-automatic rifles, electro beats, blues harps and arcade games. It was genuinely ear-boggling.

Less surprising of course were our tributes to him in the school playground. His fame coincided with that of Run DMC and the Beastie Boys and so it was inevitable that our break times were spent showering each other with spit in an effort to be the first-year’s finest beatboxer. We made beats, we imitated the sounds of scratching and, when Guns & effin’ Roses appeared, we sought to emulate Slash’s fretwork. We were shit but that didn’t stop us. It still doesn’t. If a microphone appears and literally any amount of booze has been consumed then the result is a horrible cacophony of noise. I think I sound like the amen opening to ‘Straight Outta Compton’. My friends assure me otherwise.

When sitting down to write this, I ended up falling down a beatbox wormhole. I watched clips of Sgt Jones and then remembered that I’d seen Beardy Man and Schlomo at the same festival once and so watched all their videos too. I realised that I still find it all fascinating. How can they do that with their mouths? What?! Was that two noises at once? Three? It messes with your ears and it messes with your brain. I might have to give it another go at the staff Christmas do. Sorry in advance.

What this fascination amounts to is probably better described as frustration. I love music, talking about music and writing about music. But I always feel that I never get across what a certain song or gig is actually like in terms of sound. My mouth and my ears are out of sync. My pen and my speakers likewise. I can’t make the noises (despite my best efforts) and language falls short too. There’s an episode of Peep Show in which Jeremy gets a job in a recording studio. He blows it when he tries to explain to the band where they are going wrong by imitating his preferred direction with a series of sounds and terrible metaphors. He looks like a dick and gets fired. I worry that I do this. Talking about music always seems to be a case of tragic miscommunication. There’s onomatopoeia, I suppose, but this is usually a limiting and reductive figurative tool. Beyond the staples of ‘banging’ and ‘bleepy’, I communicate the joys of a 303 as ‘squelchy’ or sub-bass as ‘rumbling’. But these words never quite hit home. Soggy trainers are squelchy too and, when I lived near Finsbury Park Tube, the whole world rumbled.

The semantic gap between language and sound is an area of much academic debate and one that Dr Helen Pleasance, Dr Rob Edgar and I dipped our scholarly toes into when we started putting together our edited collection Music, Memory and Memoir. Responding to the work of musicologists Leon Botstein and Tia De Nora, we argued for an ‘extramusical’ reading of memories and narratives that explore and communicate sound. In our methodological article from earlier this year, we define this term as ‘the ephemera and material culture that surrounds musical production, performance and engagement’. T-shirts, record sleeves, tickets and all the other stuff we accumulate have narrative shapes that are absent in sound. As a fan telling a story, the individual subject relies on the tangible to communicate the intangible. This helps to navigate the ‘slippery interface between the abstractions of sound and the narrative processes made possible in language’. As with all things narratological, it’s complex. The experience of music initiates a desire to share narrative but the unique status of sound makes this process very difficult, perhaps even impossible. It’s an idea taken further by Dr Laura Watson in her chapter in Music, Memory and Memoir entitled ‘Reading Lyrics, hearing prose: Morrissey’s Autobiography‘ (which is, of course, the inspiration for the title here). She argues that, in Morrissey’s memoir, his ‘mode of lyrical expression influenced the text’s themes and literary style’. Sound and language are entwined yet still resist one another. Indeed, Laura goes on to argue that the audiobook versions of this memoir and others ‘stand at the interface between printed word and performance.’ These are the paradoxes and discussions that make our work both fascinating and agonising. The more I read, write and listen, the more tangled and knotted the issue becomes.

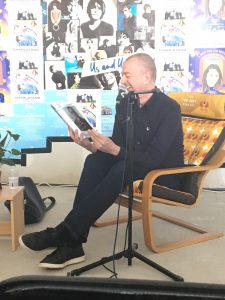

With this in mind, it was a great pleasure to read Ed Garland’s new book Earwitness. It is a significant intervention in this debate. Adding to the complexity outlined above, the author of this hybrid text has a relationship with sound that is altered by his ‘hearing loss and tinnitus’. Blending astute literary criticism and debate with memoir that is by turns self-deprecating and powerful, Garland explores the ‘sounds contained within stories and novels’. His new sonic world creates new limitations as a listener but also opens multi-sensory doors as a reader.

Garland’s writing asks that we experience sounds again. Recently, my colleague Dr Jo Waugh lectured on Olaudah Equiano and made reference to Viktor Shklovsky’s notions of defamiliarisation. Jo argued that Equiano can only communicate the absurd cruelty of the slave ship by making its material status and concrete detail feel strange and alien. Shklovsky asks that the writer ‘make the stone stony’ so that ‘one may recover the sensation of life’. There is something similar going on in this text. Garland takes the familiar world of work (crappy jobs in shops, bars and offices are surely central to our late capitalist collective memory) and renders it ‘worky’. Its soundscape is uncanny and so the unhappy pursuit of a wage becomes meaningless. Indeed, the Kafkaesque environs of the Bristol courthouse provide a ‘cloud of sonic dissatisfaction’. This is a dissonant world of ‘mutters, moans, whinges, sobs, growls, sarcastic laughs, pummeled keyboards and stifled laments’. Garland’s job as an usher provides him with a spot in the building in which the echoes and ricochets of daily conflict turn into a phasing symphony redolent of Steve Reich. A particularly memorable example of this reads:

The waiting areas of all five floors were open to each other, so a squabble by the lifts at the entrance could bounce off the floor tiles and spiral sixty feet up the central staircase, to be absorbed by the carpet outside court number nine, under the feet of a grey faced family who’ve been arguing about inheritance for so many years that there’s no longer anything left for them to inherit.

Garland’s own language is packed with sonic features. It flits between alliteration and assonance and, consequently, we hear the words themselves anew. Away from work, there are similarly unsettling (but always darkly funny) takes on shared living, noisy neighbours and hangovers spent listening to the ‘meow and yelp and howl’ of the local seagulls.

All of this autobiographical material revolves in temporal circles around the text’s narrative pivot. The author’s adult life has been shaped by the ‘endless ring of tinnitus’ and his ‘muffled’ ears. The experience itself is an example of the complexity of communicating sound. The chapter entitled ‘Not One Acute Sense’, for example, narrates the moment that Garland’s ‘tinnitus split in two’. On one side is the ‘familiar ringing’ but the other experiences a ‘rapid fluttering […] a bit like a drunken skylark practising a one-note improvisation’. Such outlandish similes demonstrate that sharing actual sonic experience is all but impossible. Language will not and cannot provide absolutes.

Indeed, one of the book’s strengths is that it resists offering such certainties, answers or conclusions. The author gets better at dealing with this new sound world by reading. This is a fluid process and far from complete or positivist. There are engagements with musicology and psychology as well as discussions regarding the material (or otherwise) nature of sound waves. This multi-disciplinary conversation provides a framework of sorts, or, reveals that others are at least asking the same questions. It is fiction, however, that provides the author with his most illuminating moments. Garland finds new ways to read. He, under instruction from Ursula K Le Guin, ‘listens’ to the texts and the noises they make. He celebrates slow deliberation over ‘frantic’ reading that ‘hoover[s] up’ words. He castigates his younger self (been there…) as someone who ‘didn’t listen to what mattered, didn’t provide any time and space in which characters could form and events could resonate’.

The reading in this takes its time and listens carefully. It responds to figures as divergent as Samuel Beckett, Ralph Waldo Ellison, Henry Miller and James Joyce. These texts all make use of sound, but like the workplace, these are sounds that are often ignored. Garland forces our ears to the page. We are encouraged to re-listen and re-think. Since reading the text, I’ve found myself doing just this. My walk to work is now punctuated by the clanging of my water bottle jostling for space in my bag. The students in my seminars speak to one another in accents that clash, blur and combine. Their mismatched vowels and dropped consonants are music. Their learning is sonic. My own reading is slower and I am conscious of my breathing as I turn pages. This is what I ask of those who are newer to reading for a living, so it is great to have this reminder that I should be doing the same.

I still think that sound is hard to write and to narrate but this text celebrates such difficulty. It offers rumination rather than conclusion. It bears re-reading and it instills new ways of doing so. I look forward to the next installment.