That brings me to meeting Miki. This is the bit of this writing that I have been putting off. It’s sitting here twenty pages and nearly eighteen months into the process. Here goes. About a year before we published our book, Rob, Helen and I hosted a conference at our university campus. Titled ‘Twisting My Memory, Man’ (the name we now use for our blog space and a tribute to our shared love for the Mondays), we welcomed a fantastic bunch of fans, musicians and writers to the event. Most of our punters were a bit of each. We had two days of great talks, performances, chats and even a bit of sunshine for the beer garden at the end. It was ace. We felt super confident about the work and excited about moving forward.

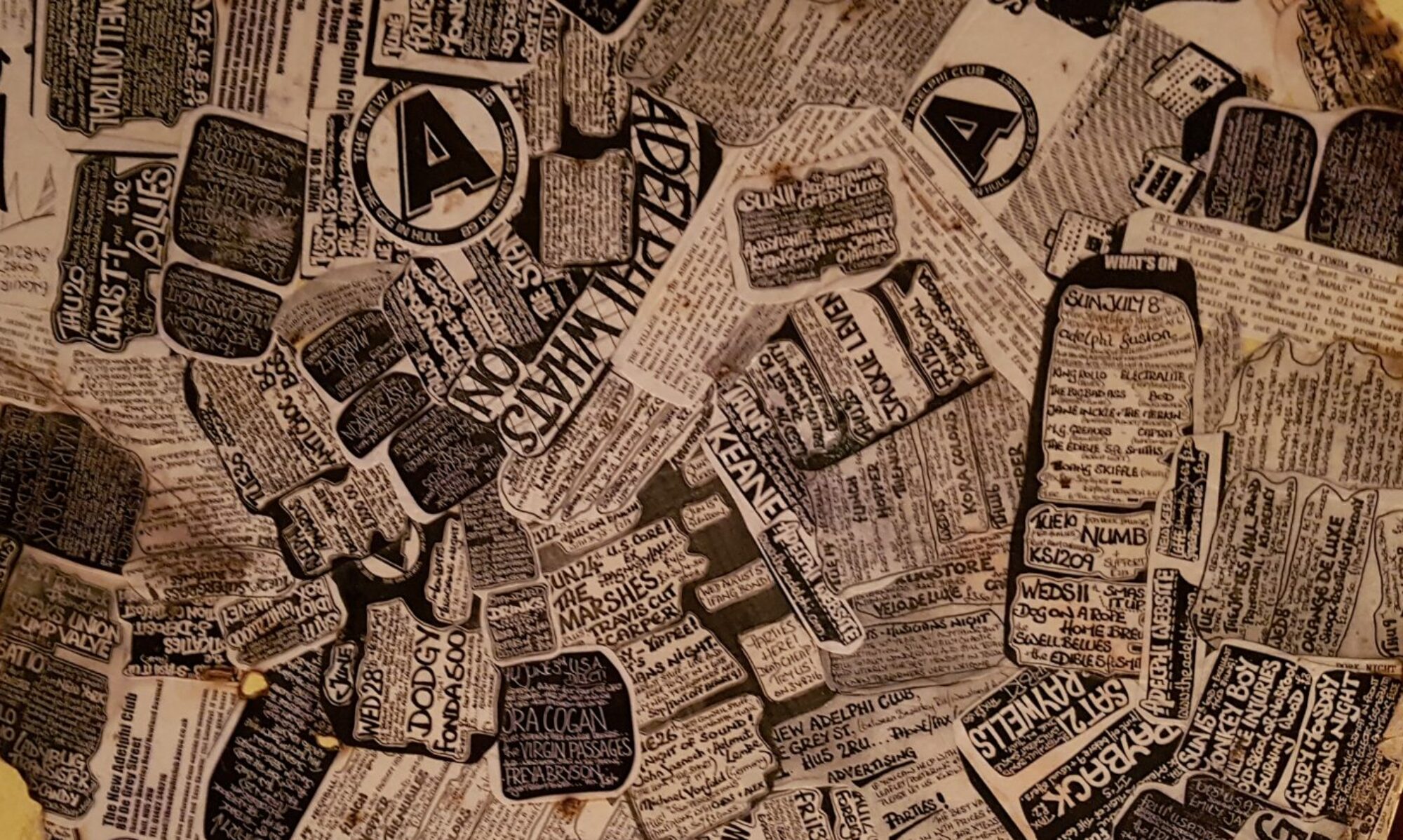

It was in this spirit of optimism that I contacted Miki Berenyi from Lush. I’d followed her on Twitter for ages and had really enjoyed her take on music and memory. Her recollections of the Lush era are illustrated by personal photos, flyers, diary snippets and bits of newspaper. These bits of visual culture tell a fantastically messy and analogue story of London’s early 90s and Miki’s part in a particular indie moment. So, I tweeted her about the conference and had a nice exchange of DMs (not the sort I used to scuff up) in which she said maybe, and I said ok. There we left it for a bit. She got in touch a few months later by email to say sorry she hadn’t got involved and I said no bother. I said I hope to see you with a guitar again and she said that she was holding one as we spoke. This would turn out to be part of the writing and rehearsal process for her new project Piroshka (more on them in a bit).

As usual, I need to fill in some background here. Try as I might, I can’t make the segue from Throwing Muses to Lush as easily as those above between the four American bands. Those bands are all part of an intermingled scene (as illustrated by Kim Deal in that woeful MTV interview) and I sort of see them as one big noisy spider diagram. Lush are from London. They sound very different to all the other bands. They sort of fit with shoegaze but that is too narrow a term. They sort of got lumped in with Britpop later in their career but were miles better than any of those reactionary bellends. Their sound is huge, noisy, frightening, soothing and haunting. Where other bands have oppositions and paradoxes, Lush are a palimpsest. Layers upon layers of guitar, a sonic whirlwind in which Miki and fellow vocalist and guitarist Emma Anderson (the same Emma Anderson whose tweet got this whole thing going) trade voices that are recognisably London and strangely otherworldly.

They also speak to a different bit of my cultural plastic bag. I grew up not far away from where they were making a name for themselves. My middle England suburb was just a travel card and Thameslink schlep away from the wild boozers and smoky venues around North London where Lush and a load of other bands were playing and being reviewed in the weeklies. I went to see bands in Camden at the Dublin Castle and the Falcon, Kentish Town at the Bull and Gate and various other spots around the NW intersections. It was a world of sweaty band merch, illegally purchased snakebite and black, badly made roll ups and endless flyers thrust into ink stamped hands. It was stupidly noisy and fucking brilliant. Scenes had edges and clear names but also overlapped. I loved the filth of Camden Lurch and still evangelise about Th’Faith Healers and Silverfish (there’ll be another bit of writing about them one day). I loved the art school posturing and off key singing of shoegaze. That wall of noise coupled with an existential gloom spoke deeply to my increasingly pissed off teenage self. I would stand before my mirror and hope against hope that I could be as aloof and distracted as Chapterhouse, Ride and Catherine Wheel. There is a little window in the early 90s that was after baggy and before grunge and all these bands sort of filled that up. I was desperate to be a part of it. It was even starting to be on the telly.

Being the story obsessed dick that I am, I am always searching for those key moments of change. They don’t really exist, of course, life is always much duller than the narratives we shape it with. Nevertheless, my Saturday lunchtime telly habits mark a low key Joycean epiphany. Football Focus and Saint and Greavsie were what my whole week built towards. It’s hard to understand it now, but there was hardly any football on the telly in the 80s and early 90s and these shows were where you might see a few goals. You’d also get Bob Wilson talking to football players on one side and Ian St John laughing uncontrollably at whatever bit of absurdist freeform mouth jazz was coming out of Jimmy Greaves. I loved it. I used to get my weekly delivery of Shoot and Roy of the Rovers on a Saturday morning, devour them both and settle down for two hours of football telly. I watched with my Dad and then we went out to watch the enormously average spectacle offered up by St Albans City of the Isthmian League. It was all pretty easy and made me very happy. Then music took over. It was music that my Dad didn’t get. He got football. We still watched these shows on a Saturday lunchtime but now they were just a precursor to the much more eagerly awaited Chart Show on ITV.

How the fuck do you describe the Chart Show? It was odd. Lots and lots of music videos stitched together by strange graphics and quasi video recorder functions. Videos would play, fast forward and pause (did they ever rewind?). Videos that played in full were augmented by a sort of DTP interface with a cursor that triggered information from a task bar. It was the sort of fluff you get from press releases alongside slightly offbeat observations about the content of the video itself. Various charts would appear on weekly rotation. The Heavy Metal chart would be announced with an animated wall that moved and rotated. It was covered with studded lights and letters. The sort of thing you’d get at the back of a stage from some hair metal nonsense. The dance videos were linked by graphics that tried and failed to say ‘tripping hard on all the drugs’. I get the visual signifiers with those two. Even in a crude way they sort of work with the music and matched the aesthetics in the videos. The ‘indie singles’ (never ‘chart’ for some reason) was different though. It used a fairground. A carousel spinning out of control was the nightmarish image that introduced the viewer to top tens that featured the Bridewell Taxis, Slowdive and, due to the nature of the label, whatever those devils SAW had put out on PWL that week (hence Kylie battling for top spot with the New Fast Automatic Daffodils). It was confusing and dissonant. But I like confusing and dissonant. That’s why I like 4AD and that’s why the Chart Show took over from Football Focus and Saint and Greavsie as the nexus of my Saturday ritual. In case you are concerned though, I still got to see St Albans go into battle with Kingstonian and Boreham Wood for a couple of years further until a Saturday job in Boots stopped all that.

It was the Chart Show where I first saw Lush. The episode was aired in March 1990 (thanks YouTube!), but I didn’t actually see it until about a year later sat at my mate Ian’s house. He used to record anything on the telly that was linked to indie. The Toyota Band Explosion at the Marquee was a recurring favourite, as was Granada’s Manchester: The New Sound of the North. He used to tape the indie singles bit of the Chart Show whenever they were on (usually every third week they shared the weirdo music segment with metal and dance) and we, with our squashy two litre bottles of terrible cider, would watch them in his living room when his parents were out. I used to think that taping stuff off the telly made Ian some kind of technical savant and that my sister, still stuck in the stone age of holding her tape recorder up to the radio every Sunday night, was some kind of luddite (I mean, she was, and she still is, but you get my point).

The episode in question is pretty amazing. If you wanted ten songs that defined indie at the start of the 90s and that defined how I saw myself at that time and that defined how my nostalgia for that era takes shape now, then these are those. It starts with Fugazi and, even though my love of the shouty testosterone bit of the American underground was a year or two away (and I am still put off by Henry Rollins’ shorts), there is an undeniable directness to the anger which speaks to any teenage boy worth his salt. At number 9 is the familiar Brummie jingle jangle of Birdland’s Sleep With Me. It’s indie by numbers and it’s pretty good. Both of these videos only get a snippet before the imaginary chart show finger hits FFWD.

The first video to get a full play is The Sugarcubes’ Planet. I love Björk and I love each of her iterations. She is a constantly evolving maverick genius and I wish there were more performers out there who share her drive and singularity. Her videos as a solo artist are famous for their Avant Garde sensibilities and for pushing video technology to its very edges. The Chris Cunningham collaboration for All is Full of Love is timeless. I’ve even seen her in full VR splendour at the Bjork Digital exhibition in 2016. So, with all this in mind, you’d think I would be all over this video. Nope, it’s terrible. The problem with pushing video technology to its very edge is that, given a year or two (or three decades in this case), it’s not the edge anymore. It’s in the middle or right at the back. This is the case here. Björk’s disembodied head floats around in a bubble across an undersea landscape (think Little Mermaid in a K-hole) before taking off to roam across the sort of mountainous vastness that had Wincey Willis panicking on Treasure Hunt. Great song of course but not a great vid. Although the info bar bit does tell us that Barry White is a fan of the band. OK.

Moving on, we hit a very young looking Ride with gaze pointed shoewards as usual. Mark Gardner isn’t quite in his floppy haired pomp just yet but looks pretty dreamy against a blur of reddy brown. Then, moving on to number six, Lush arrive as the second full video choice. The song is De-Luxe and, remember this is the first time I’ve ever encountered this band, the strangeness is instant. The vocals sit deep in the mix and the chords shift unexpectedly. The video is serious and playful. The band walk through landscape lit by strange purple light. They swing from trees and play instruments silhouetted against a red sky. The video is ego free. It seems as if the band would be wandering around this trippy half space whether we are there or not. It stands out from the videos so far for this reason. The others thus far have singers looking us in the eye, asking for some kind of tacit approval. Even bubble Bjork. Lush don’t give a shit. They offer us sound and vision but don’t care if we take it or not. Even when the video moves to a more conventional monochrome section with the full band playing, Miki only glances our way. Her focus is on that insistent guitar and its uncanny chiming. The info graphics suddenly appear to tell us that this song and the EP it comes from are getting some good press and that band all like football apart from Emma. Such banalities seem at odds with the remainder of the video as it moves into strobe and wall of noise territory. All of this sounds overblown, I know, but put yourself in the shoes (scuffed DMs obvs) of a 15-year-old me. This was new and it was strange and it was fucking magical. I was now a Lush fan. That’s all it took.

The Top five indie singles that week shows what rude health the scene was in at this time. Sitting just above Lush are NYC Velvets revivalists Galaxie 500 with a video that looks like David Lynch’s last minute homework. By way of massive contrast, the next video is Depeche Mode’s ode on shutting up, Enjoy the Silence. Clearly, it’s a massive single but the video’s atmospherics don’t seem out of place here. More country rambling (with crowns this time) and a sort of lo-fi wonkiness that probably cost plenty to achieve. The top three are super familiar and demonstrate the commercial longevity of baggy and indie-dance. Andrew Weatherall’s reworked Loaded sees Primal Scream caning it to the max at number three while a stupidly young and massively groovy Tim Burgess leads his Charlatans through Indian Rope at number two (so young and groovy that they don’t even get a video just a still of Tim). Finally, the top spot goes to yet more outside capering in the form of Stone Roses’ Elephant Stone. The fact that these three singles are still heard pretty regularly shows how much Madchester and its crossover offshoots changed the pop landscape. It also marks the moment I packed away the hoodies and flares and sought out the second hand stinko uniform I would need for my move into full indie kid status.

After that ITV epiphany, I went to Our Price after school and bought as much Lush as I could. That amounted to two things. A copy of the six-track Scar on tape and Sweetness and Light on twelve inch. I’m sad to say that the tape is long gone (now bought on vinyl from a record stall in Scarborough a couple of years ago). The single, however, is still with me and is a seriously treasured item. How could it not be? Sweetness and Light is immense. It is Lush at their weirdest, their most ambiguous and the record that shows how short-sighted journalists were when trying to put a label on their sound. Even when I fell out of love with indie later in the 90s (all the fault of Aphex Twin, jungle and the unrelenting shitness of Britpop) I would play Sweetness and Light. I still play it. I am playing it right now. You should too.

In fact, eulogising about this song is how I left it when I contacted Miki Berenyi. It seemed a good place to round off our conversation. News of a new band called Piroshka seemed like a good place to pick it back up again. Miki’s Twitter feed shared press announcements that revealed an indie all-star team were releasing an LP and going on tour. The band comprises Miki, FX and feedback legend Moose (from the band Moose), bass wizard Michael Conroy from Modern English and Elastica’s drummer Justin Welch and their stuff was coming out on Bella Union. Good stuff. One of the gigs was scheduled for Leeds’ best venue (probably the north’s best venue) the Brudenell Social Club. Great stuff. I emailed Miki and asked if me and my colleague Rob could interview her for an as yet undefined piece of writing. She said yes. Terrifying stuff.

All of my confidence about our various music and writing projects suddenly seemed outweighed by a double dose of imposter syndrome. Who was I to be making any kind of weighty scholarly claims about indie culture? Who was I to sit down with an indie superhero? Was I actually just an oldish bloke finding comfort in his records and his memories? I feared being found out. I feared looking like a dick. I feared becoming an amusing story for indie stars to chuckle at as they sipped indie cocktails in the indie members club. The nearer it got to the interview, the worse it got. I couldn’t sleep. I had, shall we say, an unpredictable tummy. I even started smoking again (any excuse). I wrote and rewrote questions. I downloaded five different Dictaphone apps so that I would look like I knew what I was doing. I stressed out over whether to wear a cool t-shirt. Would my 4AD one be too cringey? Would wearing another band t-shirt be insulting? Or, should I just go for that other staple of middle aged indie men, the checked shirt? Should I have a few drinks beforehand to settle my nerves? What if I seemed too pissed and blasé? What if I dropped food down myself?

It was a fucking nightmare. I am a fucking nightmare.

All of the stress, as it so often is, was a waste of time. It was ace. Miki is ace. When we got there, Miki and the band were mid soundcheck and then had to eat. She texted us with updates about how good her Brudenell scran was and we listened to the soundcheck from the bar. It was exciting. I had a list of questions and some idea of what I wanted to find out about Miki’s take on music and memory. I wanted to know about being on small labels and about how songs come about. I wanted to know about Lush playing in small London venues. I wanted to know about Lush playing at Lolloapalooza with a mad smorgasbord of American superstars and I wanted to ask about how her brilliantly curated Twitter feed helped to make sense of her long career. I got all of this and loads more. I’ve never written up an interview before so here goes.

There are three things to note about talking to Miki Berenyi. She is fucking clever. She is fucking funny. She swears a fucking lot. She was immediately open about her song writing process with Lush and how this differed from Piroshka, telling us that she and Emma ‘wrote separately, and it was very much one person’s vision of the song plus the producer that we were working with’. Piroshka, meanwhile, didn’t use a producer because they ‘didn’t have any fucking money’. I mean, this type of info is the dream start to an interview with an indie star. The process of creation as one that is fractured, challenging and limited by finance is sort of how I always imagined it would be. Then I asked about labels and, again, found out that lots of assumptions I had made about the creative and community atmosphere in indie land were in fact not far from the truth. To set this up a little, it is worth making it clear that Bella Union’s head honcho is Simon Raymonde who was the bass player in gigantic 4AD act Cocteau Twins. This is the kind of indie lineage I love. Miki says that, the label is, ‘very much like a family and everyone is very friendly.’ The Piroshka album is densely layered in terms of instrumentation and many of the session players came together through the label. ‘Bella Union is great in terms of making connections, everyone is good people, you know what I mean? It’s not like cold business. There’s fuck all money there, so everyone has to rely on good will.’ Certain labels are a mark of quality for the punter. It seems that this is the case for the practitioner too. Good to note also that making good music for the sake of it, for some at least, still trumps making shite music for cash.

Up to this bit of the interview, we had been sitting to the side of the stage but then the drum techs got going so we moved to the bar. Me and my colleague Rob, his wife Julia, and our indie hero Miki Berenyi walk into a bar. It was a bar with the Liverpool and Spurs match on from that day. The rise and fall of the crowd inside Anfield is clearly audible on the recording and sounds a bit like we are interviewing before 50,000 people. I still can’t quite get my head round it. I’m not a music journalist so this sort of stuff doesn’t happen to me. I am a fan first and then maybe an academic (although I’m still working that bit out) so forgive me if the rest of the interview goes in slightly weird directions.

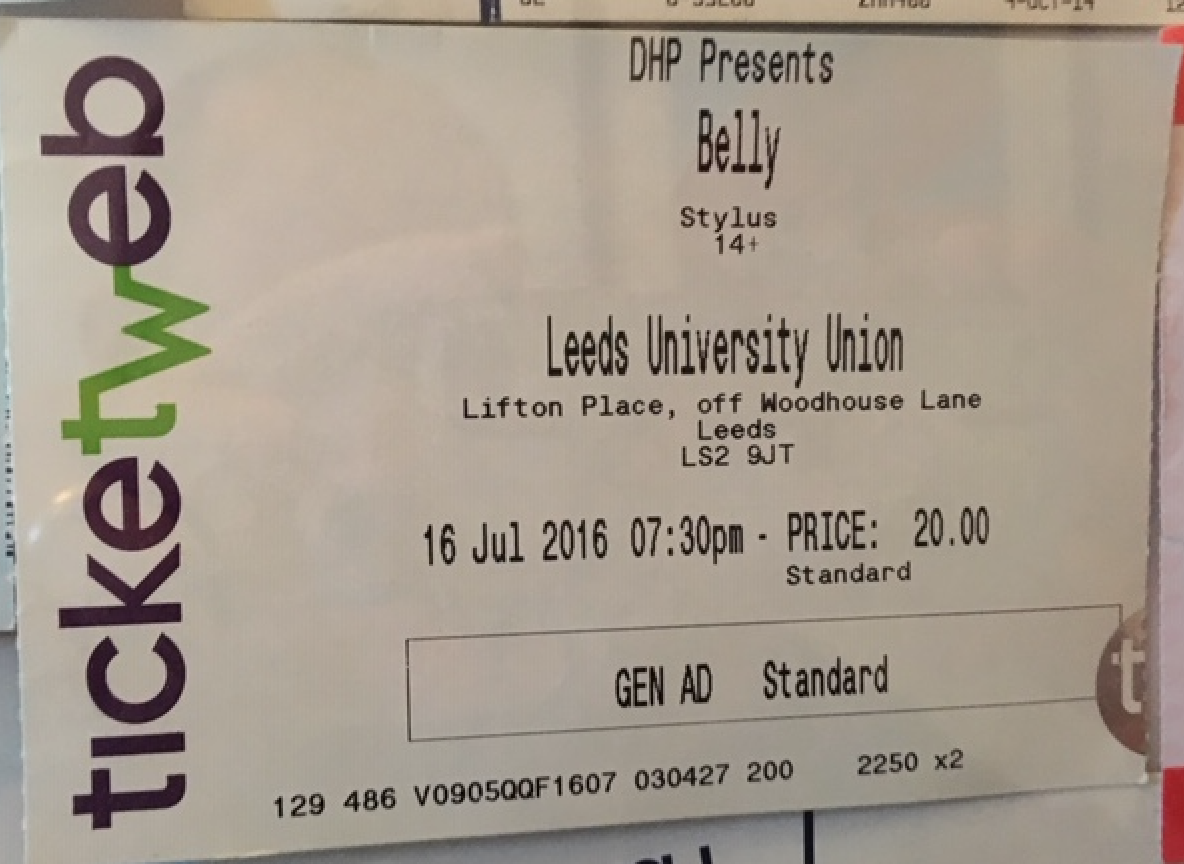

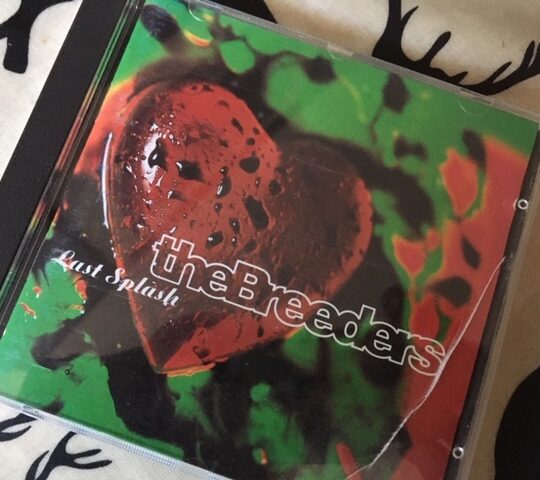

Rob’s chapter in the book I keep mentioning, as you already know, is about bands reforming. I have seen my 4AD heroes more in the last decade than I ever did in the 90s. Lush had their own reunion tour and put out some new music so that was what we asked about next. What are the reasons that bands keep doing this? Money? Nostalgia? Boredom? Why did Lush choose to join the reformed bands scene? ‘I was very ambivalent about the Lush thing, not least because of how it ended in the first place (Lush’s drummer Chris Acland tragically took his own life in 1996, an event that Miki described later in the interview as ‘like an atomic bomb going off’) and I was quite worried about it getting a bit fucked up. I was really surprised that people even remembered Lush or even cared so the fact that they did is quite a testament to us. I didn’t know because I wasn’t on social media or anything and I thought that we might sully all that in some way.’ Miki has a point here, there’s something about bands getting back together for an arena tour with merch and big money tickets that cynics might see as cashing in. While the bands that I’ve seen getting back together have been great (Belly, Breeders and Ride in particular), I hear from friends who are more Britpop inclined that some of those reunions have been, for want of a better term, dog shit. Some of the bigger players on the US alt-rock scene (cough, Smashing Pumpkins, cough) have become little more than the overblown stadium acts that they once railed against. With this in mind then, what convinced a clearly sceptical Miki to give it a go? ‘It was Slowdive, I thought they did it really well. It was quite classy, and it wasn’t too end-of-the-pier and cashing in, do you know what I mean? Especially as they weren’t all that big the first time around, so it just felt that it seemed like it was about the music. It felt like something new and I quite liked that.’

The epitome of shoegaze, Slowdive’s return has been handled beautifully. They, like Lush, returned with a killer new track. Star Roving is astonishing and, to my ears, the best song they’ve ever recorded. Similarly, Lush came back with the Blind Spot EP which contains Out of Control, a song that could have easily featured in one of my beloved ‘indie singles’ top tens. When bands do the return well, it is so often around great new material. The Breeders’ All Nerve LP is magnificent and Belly’s Dove a marvel. Playing a set that merges the old and new means that these tours are more than nostalgia. They are a mix of looking backwards and forwards and a reminder of the exciting song craft that got you so hooked in the first place. Bands that are cashing in are never going to do it well. Indie is supposed to be about more than greatest hits sets. Bands are not playlists. This is something that Miki is all too aware of, saying that a friend told her that, ‘you have to find a reason to do it other than money otherwise it will be fucking awful’. It turns out that one of the main reasons for her getting involved in the newly touring Lush was pretty personal. ‘It would be quite nice for my kids to see that I’d actually done this. There’s a whole part of my life that they know nothing about’. Ever the music fan, she worries that reformed bands are ‘clogging up the system when we should be hearing new things’. For her, the reformed bands have to be offering something ‘creative and new’. They have to rehearse and be ‘fucking good’. For those that are willing to put the work in, there are other advantageous factors in place. ‘When people are older, they’re less likely to be completely fucked on stage. When you’re young you’re more likely to just say fuck it, it’ll be alright. There’s also the fact that the technology now works, back in the day you had no chance with backing tapes, everything was totally out of sync.’

So, playing live is one way to update the past and rejuvenate our memories. What else is there? Well, as I said above, Miki’s Twitter feed is remarkable. There are photos of Lush, photos of other indie luminaries, long forgotten indie also rans, snippets from the press, diary pages, ticket stubs, wristbands and all sorts of bits and pieces. It’s like a museum of indie and it’s all curated with self-deprecating humour and an openness to conversation and chat. Miki’s not actually a fan of social media and only got involved when Lush reformed. Her initial reaction to the suggestion she started a Twitter feed was, ‘oh for fuck’s sake, alright I’ll have a go. I kept looking at what other people do, and I thought I can’t do that sort of thing. You know, fucking Trump and this is what I think of fucking Gove or whatever, you know, who gives a shit what I think? I thought the only thing I could do that would be quite charming and fun was all this Lush stuff. Then I thought there’s also this sweet stuff from some little band at the Clarendon (The Clarendon Hotel in Hammersmith, site of many fine indie gigs in the late 80s and early 90s) and from that period. It was actually like doing a school project rather than trying to build a profile.’

That period. It was only a short while, but it takes up so much of my brain. It was when I formed friendships that I still have. It was when I sort of became who I am now. It was when I bought records I still play. It was when I went to gigs in London and fell in love with Camden. So, self-indulgently, the indie scene in and around Camden and Hammersmith is what I asked about next: ‘it really started for me with me being in a band and meeting other people who were in bands, albeit very small. Like, the Valentines all lived in Kentish Town. It was local and you’d get called up asked to do a support. You could literally get a gig the next week and you’d just say yeah alright we’ll do it. There was always a really good community. There were all these little localised scenes and it was as much about the community around it. Fanzines and everyone bootlegging tapes and just being fans. Sometimes when people describe scenes, it all sounds terribly elitist like it’s some groovy bunch of people who only hang out with each other but that wasn’t the case at all. It was a free for all. All sorts of odd people, you know, whatever age, whatever gender, that’s what was so great about those scenes.’ Scenes are great in the moment, but it seems they become sullied with retelling. ‘Once the music press discover it, they try to form a pattern out of it and there isn’t a fucking pattern it’s just a pub where people go.’

From the small scale and the local, then, to the trans-Atlantic. Lush took part in Jane’s Addiction leader Perry Farrell’s Lollapalooza tour in 1992. For a teenage punter like me, this was another universe. It belonged with such exotic things as the Seattle scene, CBGBs and Woodstock. You would read about it in the NME (in fact Lush bassist Phil King wrote a diary of the tour for that very rag) and see bits of footage here and there. The bands involved were all part of that moment when American indie went mega-boom and seemed to take over everything. Lush’s main stage mates were Red Hot Chili Peppers, Ministry, Ice Cube and the Jesus and Mary Chain. Huge bands with power chords, big shorts and tops off, a controversial and antagonistic hip hop artist and Scottish blokes involved in an eternal sulk with each other. It seemed so odd at the time that a band with a complex and sensitive sound would take the stage with such a macho line up. It still seems odd now. It’s like once the alternative boom happened the scenes got muddled up. Pre Nevermind, you knew your industrial from your Glaswegian noise and your grunge from your shoegaze. Suddenly, all bets were off. If you have long hair and look like you might graffiti an anarchy sign on the back on a toilet door then you’re in! If you listen carefully you can hear the NME and Melody Maker gatekeepers tripping over each other as they rush towards you. If you look at the horizon you can see the bookers from Rapido and The Word punching each other out of the way. It was a musical free for all and Lollapalooza seemed to be the epitome of all this. As a fan, I liked the local and accessible. Indie made sense because, despite the strangeness and intellectual ambiguity of the sound and aesthetic, you could imagine being in band just like your heroes (although, to be fair, all of my own efforts were beyond shit). Giant stages and Flea’s cock sock were not quite the same.

How did it feel for Lush? ‘What was really good about that Lollapalooza was that it was only the second one, it was still quite a new thing, and everyone was really excited about it. We were like fucking hell we’re on this bill with all these really fucking heavy bands. Pearl Jam actually were booked to be on after us and then they got massively popular and their fame went fucking ballistic. But Pearl Jam being really lovely guys said they would still go on just after us and that was great because loads of people turned up early to watch them.’

From my telly screen, Lollapalooza always looked sort of corporate and hierarchical, but Miki says that this was only really the case in later years when it became ‘first stage, second stage, VIP this, guest list that’. The year that Lush joined though was ‘really loose’ and ‘bands were hanging out with each other, people were riding on each other’s buses, it was really good fun. People wanted to be friendly, it was like joining a circus.’ All of this is really refreshing to hear. It sounds as if, when it comes down to it, bands are bands. It’s only when the press and the sponsors get involved that it all gets crappy. For an indie fan, that’s good to hear.

In fact, it’s the press that come in for a bit of kicking as our conversation draws to a close. Their simplistic categorising of scenes and regional movements has, with the passing of time, revealed some unpleasantness about the music media of the early to mid 90s. This is especially the case when compared to the way that bloggers and social media users are now offering detailed reviews of bands and sharing them directly with the performers themselves. ‘People write quite involved reviews and they work really hard at saying something positive which I don’t think is a bad thing. This is probably why the music papers have died a death. When I look back on the music press it is important to remember that they gave lots of young writers from all sorts of classes a chance to get involved. You could be some kid in Glasgow and get your review from a gig at King Tuts out there. But, on the negative side, when some of the journalists decided that they would slag a band off it left lot of fans quite isolated. Suddenly there was no place to get your happy information from. It’s like every time Ned’s Atomic Dustbin get mentioned it’s just slagging them off. So, where do fans find their connection?’

Fans will remember the familiar process. Find a scene, name a scene, destroy a scene. ‘It’s a way to diminish it all. Some of it was just like fucking trolling really. Anything that a band did would be met with some sneering comment. I think the music press got a bit out of control and went very tabloid. I know it’s fine to have a bit of rapier wit going on, but it got to the point where they were either totally up someone’s arse and that band couldn’t put a foot wrong while other people were shot down and bullied. I really remember it with that whole Manchester thing. It was juxtaposed with shoegaze. We were all supposed to be soft southern wankers and Oxford kids against all the having-it-large Mancs. Half the fucking writers saying this had been to Oxford and it’s not like Slowdive were part of the landed gentry. It was like, if you’re in with us we’ll overlook any problems, if you’re not then we’ll fucking go for you.’

This sort of petty tribalism only got worse as Britpop arrived. Alongside the depressingly reactionary sounds and English exceptionalism came a new celebration of crass boorishness. Being a dick was supposedly just an ironic take on British culture. No, it wasn’t. it was being a dick (chasing page three girls around in your video, really?). The music press dutifully played their part in this shift downwards to tabloid idiocy. I was at Uni during the moronic Blur/Oasis thing (for the record I thought both were terrible and still do) and it was a bad as you probably think it was. Stupid coked up men in shit bands slagging each other off. Videos and magazines that had all the sophistication of the Benny Hill Show. This was indie culture? Nope, this was the sort of crap I’d tried to avoid by getting into indie in the first place. For Blur and Oasis in the mid 90s, read hair metal in the 80s or Pharrell and Robin Thicke more recently. It’s dull, corporate nonsense. Britpop’s finest were thoroughly obnoxious in that way stupid coked up men in shit bands usually are. But they got away with it thanks to a compliant press eager for easy stories. The sense that we were back to a big boys’ club was palpable.

‘Because the press bought into it all wholesale, there was no real challenge to some of the outright misogyny amongst some of those bands. I thought it was remarkable that they weren’t going to mention the way that they were talking about women at all. You know, you’re a journalist, do your fucking job properly. When you get that kind of ‘women in rock’ cliché that the NME or the Melody Maker would do every now and again, I think it was quite well intentioned, but the problem is that it immediately puts you in a niche. You also end up with people who should know better, people who you thought were in your own tribe, going along with it and then turning on someone like me and saying shut up, you’re spoiling the party. So, you think, really? Ok, that’s interesting, a few years ago you were all Greenham Common.’

Miki says she felt, ‘betrayed by her own’ as the 90s moved into their second half and I get what she means. All of the progressive politics and intellectually ambitious art sort of went out of the window the day that Alan McGee and the Gallaghers decided that world domination was on their to-do list.

Like loads of indie kids, I had a tantrum in the late 90s. I walked away from it all. I went to clubs, raved in festival dance tents and got more interested in decks than shoegaze FX. Indie and lad culture had got themselves into a dumbed down and drooling Faustian pact. Between the late 90s and the middle of the noughties, I don’t think I bought any guitar music at all. I missed out on all of the NYC hipster stuff and gleefully absented myself from the surge of landfill indie dominating the radio and the arena gig scene. My label love shifted to Warp, Rephlex and Ninja Tune. It was in these places that I found those same complexities and juxtapositions that I’d always sought out in 4AD.

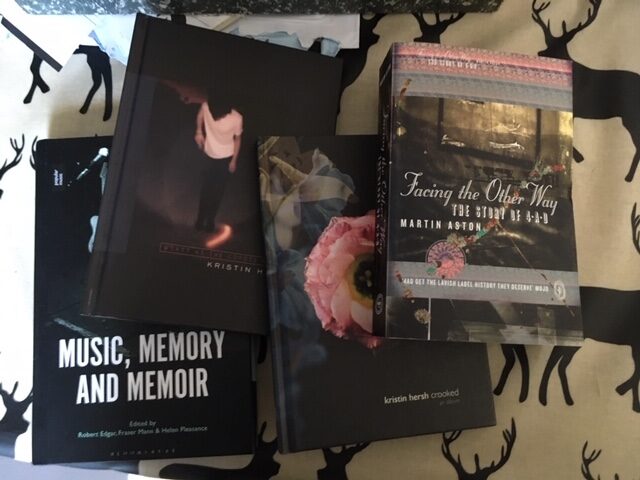

Then I grew up a bit. I saw Pixies at V2005 (awful festival BTW) and loved it. I pined for indie. I wanted jangly, chiming guitars and off centre ideas. I realised that I could like both. I could lose my shit at an indie gig just as much as I could watching Orbital and their techno specs. And that’s sort of been the way ever since. I love loads of labels now. As well as 4AD, there’s Heavenly (30 years old now), good old Rough Trade, my exciting American lover Sub Pop, loads of esoteric and magical dance labels and, appropriately enough for this ending, Bella Union. I say appropriate as I want to end up with me, Rob and Julia watching Miki and her band in the Brudenell gig room. It was only last year but the thrill of watching humans make extraordinary noise together was a fresh as it had been when I stood in those same rooms in 1991. Bella Union make me feel the same things that 4AD always have. Their roster is impeccable. Decisions are made based on music. Their artists can make me spiral through the full gamut of emotion with a simple riff or turn of phrase (John Grant gigs are overwhelming in their power, intensity and intelligence). Their artwork is cool. Plus, they have the Miki seal of approval.

If our interview with her proved anything it was that all my dearly held ideas about indie authenticity were sort of true. As I get older, it can be easy to dismiss the stuff I used to believe in as naïve or posturing rubbish. I get more cynical and less trustful. Miki’s love of music and her insistence that the music comes first is evidence to the contrary. I can believe in good music people and the labels that help them. If that’s the case, then staying loyal to 4AD for so long actually means something. It gives me a moral and cultural framework of sorts. People exist that do things for the right reasons and that is always going to be something worth my loyalty. If they keep doing it then I’ll keep buying it. I’ll probably keep banging on about it too. Just not on the radio.