It is critical when engaging in a practice to keep a record of activities which have enabled the final product. I believe that the images displayed in this chapter actively work to reflect how we disabled the performance externally via the set.

Lehrer (2012) says ‘It is notable how naturally a discussion of the creative activity of the artist moves to the experience of the artwork, which may be an experience of someone other than the artist, as well as the artist.’ In this distinct case, the collection of images acts as not only a demonstration of the work but also a demonstration of our thoughts and feelings. Firstly, I will refer to space itself, whilst not directly depicted in the images, it was an integral part of the decision making process and another dramaturgical concept, that of ‘intimate theatre’. This wave of theatrical developments is secondary known as ‘writing of the self’ – as I have previously addressed, this was done through our own variety of storytelling. Typically intimate theatre is led by a desire for authenticity and requires us to enter into an open relationship vis a vis with the audience. In a way, we expressed a deep level of intimacy with the aforementioned ‘sex scene’. The simplicity of two people back to back, aided with the cripping of the text [as detailed below] gave us an opportunity to explore the character’s inner desires, inner complexities, and emotions which are forbidden to be present [if you suspend your disbelief and presume we are in Dachau].

Second, to this, the use of water in the space was a careful one. Upon initial thought, it was introduced as a criptology, breaking the original play’s climax from the electric fence to a far more relatable end. By relatable, I simply refer to that of local interest and news. Water also has multiple connotations, on the one hand, it is a symbol of life and rejuvenation, it shapes over 70% of the world and a large proportion of the human body. A baby born in water can survive there until the moment they take their first breath of oxygen. In that singular moment, we become susceptible to the frailties of the human body. By performing, covered in water, we allowed our bodies to succumb to the impairments the water provided, a weighting which hindered movement, a cold which hindered physical sensations. Again, this was ultimately a personal reflection on the implications of my own disability on my own body.

Space itself, defined colloquially as a ‘black box’ provided the perfect stage for Bent to take place. It presented the potential for an open and intimate performance, as you can see demonstrated in the image below. In order to permit an authentic performance, we wanted to keep the set as minimalist as possible. In doing this we felt that the concentration of the audience could re-focus from admiration of their surrounding to the action in the space. This would, therefore, engage the audience in a more critical role than passive, as previously mentioned. It is also worth noting that the audience was free to accept that the space was indeed the Arts Workshop, on a Friday afternoon in mid-May. But what was also intended is presenting the dual identity of the space, allowing the audience to be [for a brief time] transported.

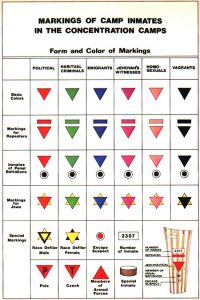

The final concept for us as artists was reflecting on our own personal impressions which we left on Bent. That being the messages we gave in our auto-biographical moments. Each moment referred to identity, not our own, but of those around us and the subjects of the play. Even in the 21st century, I find it astounding of how simple it is to assign a label to someone, without context, without investigation. Be that ‘gay’ or ‘cripple’. Similarly it is equally surprising that when a civilisation is assumed to have progressed to much, we have not come very far and there are still walks of life which are deemed as lesser [in some circles] and thus we explored the metaphorical relationship of dirt and dirty and the connotations of such with regard to homosexuality, the state of Germany in late 1930s-40s and as a contemporary reflection on attitudes to what we deem as ‘other’, that we don’t quite understand.

Hi, this is a comment.

To get started with moderating, editing, and deleting comments, please visit the Comments screen in the dashboard.

Commenter avatars come from Gravatar.