Introducing The Humberhead Peatlands

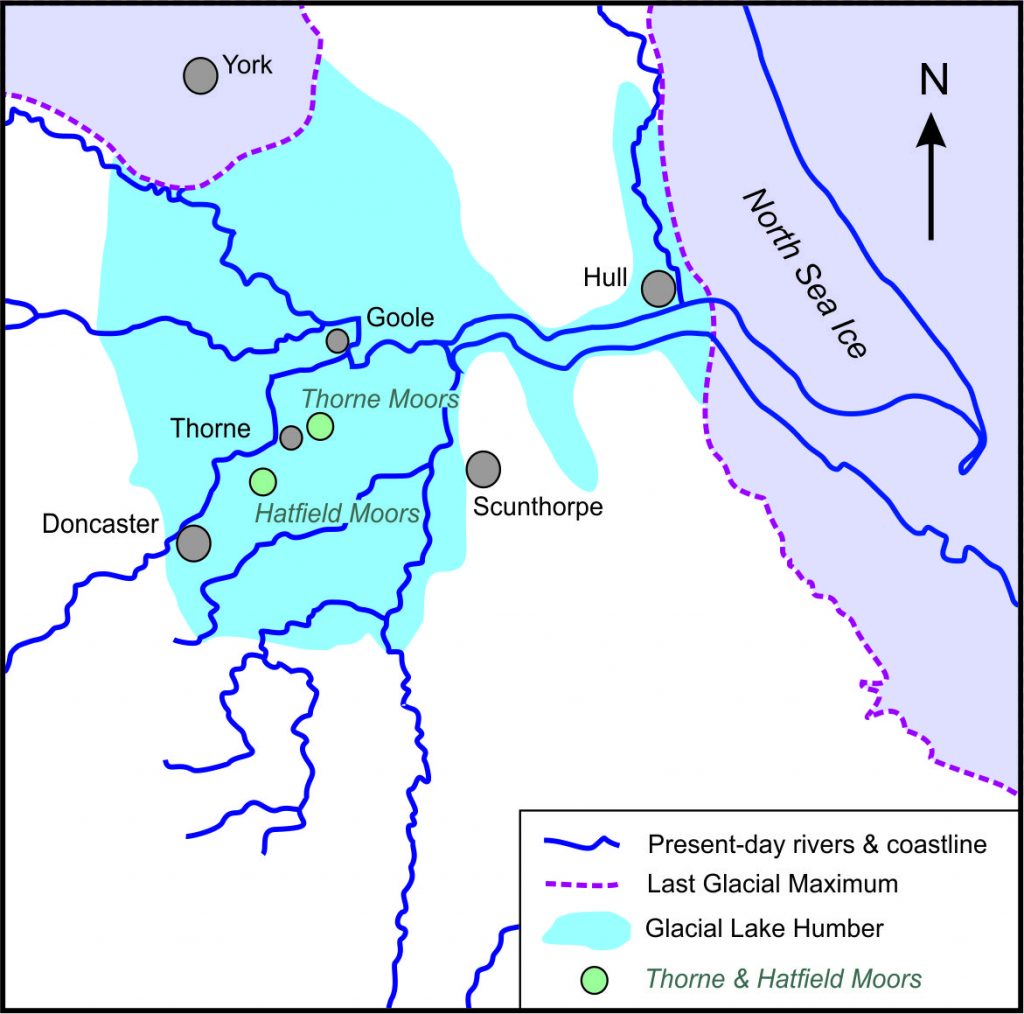

The Humberhead Peatlands National Nature Reserve (Figure 1) sits within an area known as the ‘Humberhead Levels’. This large area of flat land lies at the head of the Humber Estuary, on the Lincolnshire/Yorkshire border. Its elevation is at (or just below) the current high water mark in the estuary. The Humberhead Peatlands are the largest remaining example of a remnant ‘lowland raised bog’ in England.

The Development of the Peatlands

During Britain’s last glacial period, a large meltwater lake occupied the area shown in Figure 2, bounded by higher ground on the west, south and east, and by ice to the north. As Britain’s glaciers declined Lake Humber silted up. Research by experts in ‘palaeoenvironments’ (past environments) tells us that forests then developed, particularly with oak (Quercus) and pine (Pinus) species. By 5000 years before present, water levels were rising and a bog had gradually formed and expanded.

The habitat here was varied, with regular periodic expansion of trees across the peat surface to form mire woodlands. But by about 4000 years ago the woodlands were being submerged in freshwater, and the peatland expanding. Rather than reflecting a wetter climate, this was probably cause by forest clearance in the uplands that drain into this area. Trees use up water. Fewer trees means more rainwater reaches the rivers and flows into lowland areas. So the very presence of the peat may be partly because of human activity several thousands of years ago.

Human Impacts Reshaping the Bogland

Over the last five centuries two human activities have had profound impact on the peatlands: land reclamation for agriculture, and peat cutting. Each affected different parts of the moor at different times.

The practice of peat cutting for fuel was established on the moors by the 13th and 14th centuries. Local place names may reveal something of how people saw the moors at that time. We come across frequent references to ‘Hatfield Waste’ and ‘Thorne Waste’. You can still see the latter on Ordnance Survey maps today.

The late 17th century saw an enormous effort to drain the southern part of the Humberhead Levels for agriculture. This work was led by Dutch engineer Cornelius Vermuyden. It was not entirely successful, to say the least. It led to local rioting, and the Government had to order remedial work to be carried out.

The use of peat for fuel was diminishing by the early 1800s, as people turned to coal. Locals made further attempts to improve the land for agriculture through the practice of ‘warping’. This involved cutting channels inland from the estuary to enable fields to be flooded at high water. The water receded as the tide fell, depositing silt in the fields. This process repeated multiple times would gradually build up fertile agricultural land.

By the late 1800s the economic conditions for both agriculture and peat were changing. Bedding straw was in short supply and peat litter was a viable an alternative. Along with other uses for peat such as packing, disinfecting and fertilising, this gave Thorne and Hatfield Moors new commercial potential. A number of companies began cutting the peat, draining more land as they did so. These small companies merged in 1896 to form the British Moss Litter Company, which was then acquired by Fisons in 1963.

Fisons promoted peat as a replacement for garden compost, both through its marketing and through the development of products such as grow-bags and plant pots. The company introduced mechanical peat extraction methods, with ‘peat milling’ removing the top layer of peat over very large areas. This expanded the area of moor affected by peat cutting. In 1910, 70,000 tonnes of peat were cut from an area of around 500 hectares. In 1985, peat milling produced 25,000 tonnes, but from an area of greater than 1000 hectares.

Figure 3 shows Swinefleet peat works, which has been derelict since 2000, with the remains of milled peat left at the site.

Humberhead Conserved

The shift from peat extraction to peat conservation happened in the last 40 years or so. In the mid-twentieth century Thorne and Hatfield Moors were still thought to be of little value. Yorkshire County Council proposed to use Thorne Waste as a dumping ground in the 1960s. In the early 1970s it was considered as a possible site for a new airport. The value attached to the moors changed largely because of the efforts of local naturalist William Bunting, and the protests he organised in the 1970s. Parts of Thorne Moor were designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest in 1981. The designation of the National Nature Reserve followed in 1985. English Nature (now Natural England) then acquired the land in the early 1990s.

Even then, peat extraction continued through a leaseback agreement between English Nature and Fisons. The peat cutting left an average of just 0.5m depth of peat for future restoration and conservation. In 1995 the nature reserve expanded to its current extent. Peat milling continued at Hatfield moor until the early 2000s. A peat mill remains in operation there today, processing peat imported from other countries.

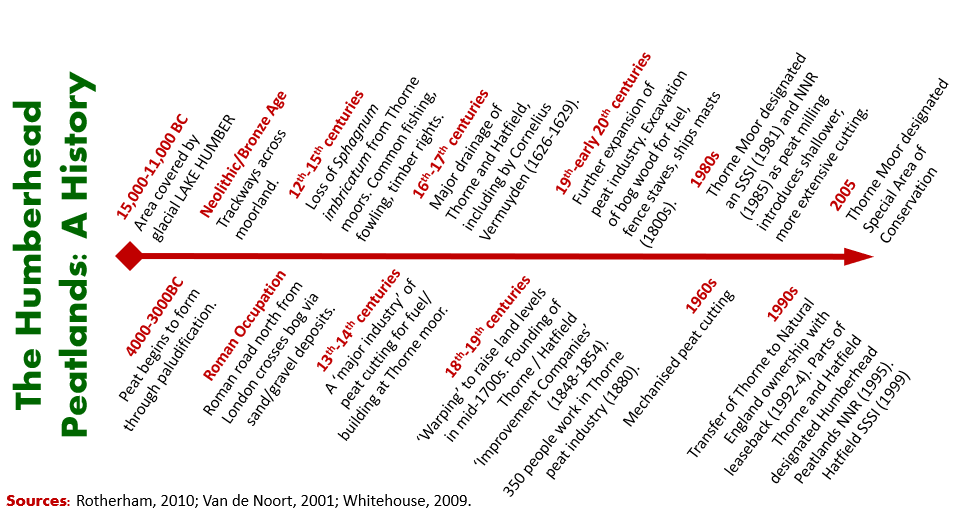

Humberhead – A Timeline

References

This account has drawn on the following readings:

Boswijk, G. & Whitehouse, N.J. 2002 Pinus and Prostomis: a dendro-chronological and palaeontomological study of a mid-Holocene woodland in eastern England. The Holocene 12(5). 585-596.

Caufield, C. 1991. Thorne Moors. St Albans: The Sumach Press.

Creyke, R. 1845. Some account of the process of warping. From the Journal of the Royal Agricultural Society. British Farmers Magazine Vol IX, New series, No XXXIII. 30-36.

Knittl, M.A. 2007. The design for the initial drainage of the Great Level of the fens: an historical whodunit in three parts. Agricultural History Review 55(1). 25-50.

Rotherham, I.D. 2010. Yorkshire’s Forgotten Fenlands. Barnsley: Wharncliffe Books.

Smart P, Wheeler B and Willis A. 1986. Plants and peat cuttings: historical ecology of a much exploited peatland – Thorne Waste, Yorkshire, UK. New Phytologist. 104. 731-748.

Smith, T.M. 2012. Enclosure & agricultural improvement in north-west Lincolnshire from circa 1600 to 1850. University of Nottingham. PhD Thesis. http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/12489/1/Tom%27s_Thesis_complete_%28slimline%29.pdf [accessed 07/06/18].

Van de Noort, R. 2001. Thorne Moors: a contested wetland in north-eastern England. In Coles, B; Olivier, A. & Bull, D (eds), The Heritage Management of Wetlands. European Archological Council. 133-140.

Whitehouse N. 2010. Conservation lessons from the Holocene record in ‘natural’ and ‘cultural’ landscapes. In Hall M. (ed), Restoration and history: the search for a usable environmental past. Routledge, London. 87-97.