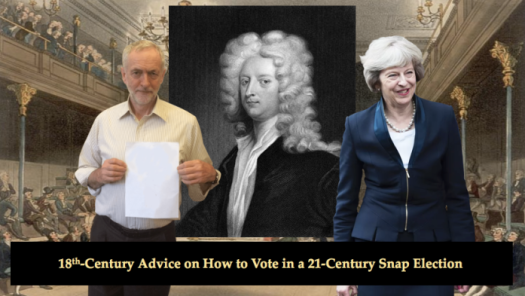

By Dr Adam J Smith, lecturer in English Literature

The claim that we are living in ‘unprecedented times’ is itself becoming disconcertingly ‘precedented.’ This is perhaps to be expected when we live in a world where Britain’s Foreign Secretary hosted Have I Got News for You and the White House is occupied by the presenter of the American Apprentice.

In 2010, a coalition government seemed unprecedented. So too did the gradual corrosion of health-care services, the dismantling of the arts and culture sectors, the commercialisation of higher education, the rise of foodbanks and record levels of homelessness. Then there’s the close results of the Scottish Referendum, the heady triumph of Jeremy Corbyn, the widely-reported implosion of the Labour party and, of course, the vote for Britain to leave the European Union. Unprecedented is the new precedent.

And now, three years ahead of schedule, there will be a General Election, due to be held just six weeks after it was announced. Not only will this be a challenge for the politicians involved, faced with the unprecedented challenge of condescending three years’ worth of planning into less than the amount of time it takes to broadcast a season of Broadchurch, but this also presents an unprecedented challenge for voters.

Since we all seem to be living in a particularly demented episode of Black Mirror it might be easy to feel like there’s nothing to be done. You may feel like you never get what you vote for. You may feel frustrated and disillusioned. You may feel like it isn’t worth voting because there’s no point. If you feel this, ignore that feeling. You should feel frustrated and you should feel disillusioned, but the only way to assert your will upon government is to vote.

But why keep voting, and who should we vote for anyway? These are good questions, and (as ever) the eighteenth century has the answers.

Eighteenth-Century Guidance on How to be a Good Citizen

Cards on the table, all my research is on the relationship between citizens and the state, and on how that relationship is articulated (and effected) by literature. I work on the long eighteenth century and as part of my PhD I spent a lot of time working on a periodical called The Freeholder, written by a man named Joseph Addison.

Addison too lived in ‘unprecedented times.’ The execution of Charles I by parliament, the Glorious Revolution and the Hanoverian Succession all remained in living memory and each raised serious structural, institution and existential questions. The emergence of cheap print meant that there was plenty of advice out there on how to vote, and The Freeholder offered just such advice. Published twice a week across 1715-16, Addison’s paper sought to tell property-owning gentleman (the only demographic allowed to vote at the time) what to think about when completing their ballot. Much of this advice remains extremely pertinent today, so here are three things to bear in mind as you march down to your local memorial hall on polling day.

- It isn’t about ‘winning’, it is about representation

From the very first issue of The Freeholder Addison refers to his vote as being his ‘remote voice’ in parliament. He writes that ‘the House of commons is the representative of men in my condition. I consider myself as one who gives my consent to every law that passes.’

Addison’s MP represents him. He needs to choose an MP whose interests and agendas closely match his own so that he can then trust this MP to vote and behave in parliament as he would himself. That MP is his ‘remote voice’, making a case in Westminster on Addison’s behalf whilst Addison is at home writing his periodicals.

Crucially, contrary to the way that it is often portrayed in the media, the party who win power during a general election cannot do whatever they want. Everything needs to be debated with everyone else that we voted for, and if they can’t get a majority vote they can’t move forward. We’ve seen a lot of this in the last year. Some people have even suggested that the main reason we’re having a snap election is because the party in power can’t get what they want with the house in its current configuration…

If you vote for a party that doesn’t win, that party doesn’t just disappear. If enough people vote for them they will be represented in the House, which means that they form part of the opposition. They offer an alternative opinion to the party in power and they’ll have to vote, on your behalf, on all these big decisions.

Vote for who best represents you so that those views can be aired in parliament. You’re choosing your own ‘voice’, so choose carefully.

- You’re voting for a party, not a prime-minister

In Addison’s Freeholder, the ‘happy tribe of men’ who make up a political party (a slightly loser affiliation that we know today… for now at least) are more important than the person leading them at the time. The principles of the ‘party’ will persist far longer than the individuals representing them at any given time, and this is perhaps useful to bear in mind today, given that in neither Labour or the Conservative currently have the same leader that they had going into the last general election in 2015. As Addison says in The Freeholder, all politicians are but ‘blossoms in the wind’ whilst government itself is an oak, rooted in the earth.

Again, vote for the party that best represents you and try not to get embroiled in ‘personality politics’, another twenty-first phenomenon that Addison warned us about three hundred years ago:

When a man thinks a party engaged in such measures as tend to the ruin of his country, it is certainly very laudable and virtuous action in him to make war after this manner upon the whole body. But as several casuists are of opinion, that in a battle you should discharge upon the gross of the enemy, without levelling your piece at any particular person so in his kind of combat also, I cannot think it fair to aim at any one man, and make his character the mark of your hostilities.

The Freeholder, No. 19 (1716)

- Omission is a greater crime than commission

This was the big one for Addison, who explains that ‘the great crime of omission is an indifference in particular members of society.’ He explains throughout The Freeholder than it is in fact worse to not do something right than it is to do something wrong. Addison’s overarching argument is that all citizens entitled to vote have both a duty to remain politically engaged and a personal responsibility to ensure that their MP are representing their interests. Again, this is because according to Addison he has lent his own voice to his chosen MP. He wants his voice using properly. As Addison puts it:

A freeholder is one remove from legislator, and for that reason ought to stand up in the Defence of those Laws which are in some degree his own making.

The Freeholder, No. 1 (1715)

It is stated throughout the Freeholder that it is this connection between citizen and state that constitutes the greatest ‘privilege’ of living in a democratic society. It is, for Addison, what gives the governed power over those who govern and, as we all know, with great power comes great responsibility.

If a citizen chooses not to be involved in the process and turns away from the business of politics then they no longer have any stake in who represents them in government. Their views, thoughts, attitudes and opinions and lost. As Addison highlights, this is not only their loss, but the loss of anyone else who shares their outlook, who similarly would have benefited from their vote.

What about this snap election?

Quoting Addison is all very well and good but he died in 1719, so what good does it do to read his work now?

Well, you need only look at the Gothic buildings that house our parliament to see that the one thing we can count on to remain unchanged, even in unprecedented times, is the mechanics of government. Addison’s advice to voters, then, remains relevant.

What would Addison want us to remember? Be engaged. Think about who best represents your thoughts, opinions, attitudes and interests and vote for them. Think more about who you want to represent you in parliament than who you foresee as the party in power. Look at the party more closely than you look at the people inside the party and remember, your vote is your voice. If you choose not to vote you have no voice, but if you vote wisely, your voice will be heard in government.

Disclosure notice: Joseph Addison was affiliated with the Whig ministry, a party opposed to the Tories.

This post originally appeared on Adam’s own blog, ‘The View from the Coffee House’, where you can find out more about his research:

https://adamjsmith18thc.wordpress.com/

Read Addison online for free at Project Guttenberg:

http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/12030

Register to vote:

https://www.gov.uk/register-to-vote