By Dr Adam J Smith and Dr Jo Waugh

Is satire dead? Journalists such as Emma Burnwell and Toby Young have confirmed its demise, as have satirists themselves, like Armando Ianucci and Stewart Lee. The cited causes of death vary (sometimes Brexit, often Trump, always social media), but they are consistently urgent, recent and contemporary. But are reports of the death of satire greatly exaggerated, premature, or just familiar? In this post, we trace such proclamations back to the eighteenth century, and reveal that the observation itself is a satirical device usually only deployed in times of social and political extremis.

Satire seems dead when the truth is uncertain. How can the satirist confidently hold a mirror up to vice and folly and expect a straightforward reflection, in a “post-truth” world of “alternative facts” and “fake news”? Yet many of the satirists now suggesting the death of satire emerged and flourished in the era of “spin.” The generation of satirists to which Iannucci belongs (Steve Coogan, Patrick Marber, and Chris Morris) were prolific during the Blair administration when “spin” was the less alarming predecessor to “post-Truth.” The Friday Night Armistice, The Day Today, Brass Eye, and The Thick of It held up the follies and vices of a culture apparently obsessed with celebrity, and distracted by elaborate but meaningless graphics on the news.

But there is also a tradition of proclaiming the death of satire when the truth is certain, but unpalatable. American singer-songwriter and satirist Tom Lehrer is often credited with the phrase, having lamented in a 2003 interview that ‘political satire became obsolete when Henry Kissinger was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.’ During the interview, Lehrer commented that he wouldn’t be writing any satirical songs about then President George W. Bush for fear of making palatable a very real threat to the American people. It is a strikingly prescient argument, given Iannucci’s current position. Comedian Robin Williams offered a variation on this same theme, observing two decades that: ‘People say satire is dead. It’s not dead; it’s alive and living in the White House.’

Alternatively when the truth seems clear but unsayable to the would-be satirist, satire is once again dead. Armando Iannucci has commented that “offence” is the satirist’s intention, but that we now live in a climate where the intention to offend must always be disavowed. The notion of the unsayable offence goes back to poet and satirist Alexander Pope, who grieved the form in his ‘Epilogue to the satires’:

So—satire is no more—I feel it die—

No Gazetteer more innocent than I—

And let, a’ God’s name, every fool and knave

Be graced through life, and flattered in his grave.

As is the case in many of the examples given above, Pope’s political affiliations find him in opposition to those in power. Pope was an openly Tory poet, writing under a Whig government. The impulse to announce that political culture has become so outlandish that it is impossible to discern satire from social reality is revealed here as being itself a satirical device that has enjoyed currency for the best part of three centuries.

Pope even flags this in the following line, knowing full well that as editor of The Dunciad (a vindictive, incendiary and famously merciless work of serialised satire) he is anything but an ‘innocent’ Gazetteer. Pope’s ironic relief that in satire’s wake ‘every fool and knave’ will be left to enjoy a charmed life and sycophantic celebration in death is in fact precisely the opposite: a condemnation of the suffocating politeness perpetuated by his Whig opponents. Essentially, Pope is complaining that satire is dying because political correctness has gone made. Literally nothing is new.

Yet the perceived problems of political correctness as a stifling force have been fruitfully seized upon by, for example, Stewart Lee, for whom the announcement and autopsy of satire has become a regular routine. The figure of the ailing comedian fearful for the future of the form in the face of increasingly bizarre current affairs is now fully a rounded and recognisable comic entity whose satirical targets include not “PC” but the very notion that “PC has gone mad.”

The paradox of the ‘death of satire’ is that the proclamation is itself a satirical act with a significant literary history. Stewart Lee is not going to go out of work anytime soon. This brief survey also reveals it is a satirical weapon deployed in social and political extremis: be it the surprising longevity of the opposition’s position in government, the unlikely presidencies of Reagan, Bush and Trump, Brexit or even the social reorganisation wrought by the rise of social media.

When satire is declared dead, it can mean only two things. First, satire is alive and well. Second, our satirists are worried, so we should brace for impact.

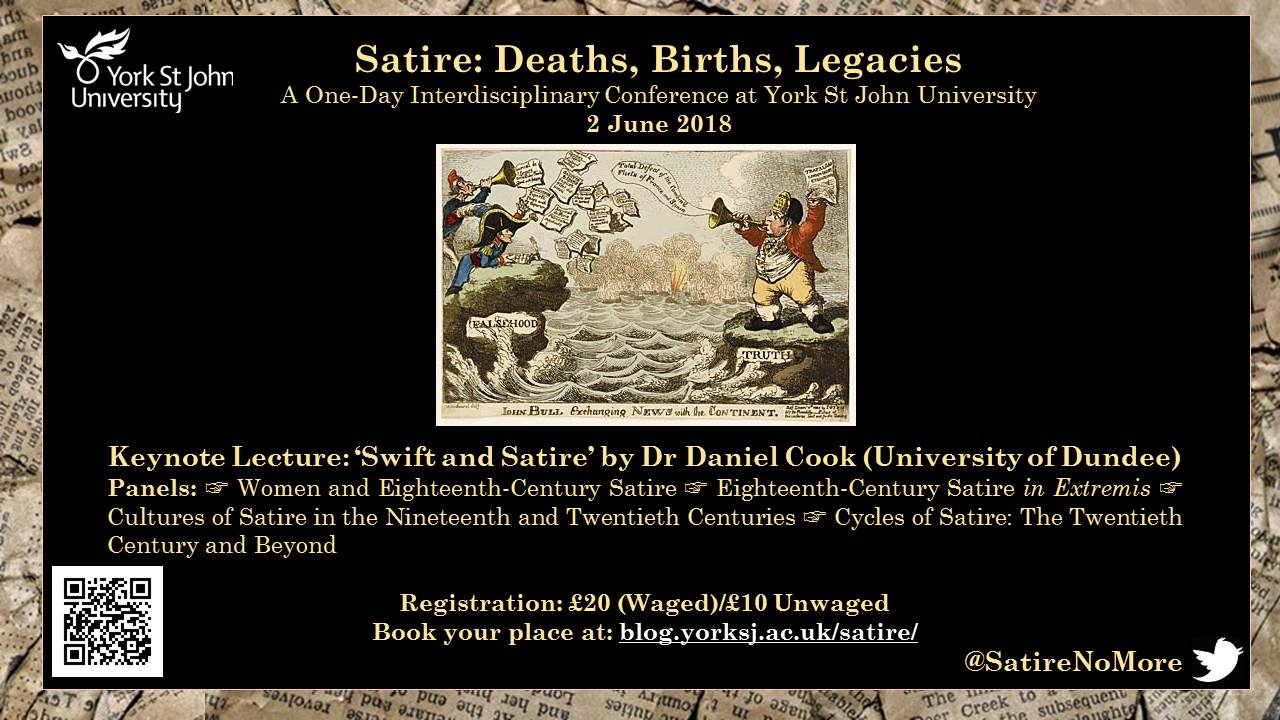

Satire: Deaths, Births, Legacies, 2 June 2018: An interdisciplinary conference exploring the form, function and future of satire, from 1688 to the present day.