Literature student Michaela Bosman, recently returned from a Pagoda Sustainable Global Experience internship in Brussels funded by the Careers and Student Opportunities Team, reflects on her transformative learning on the trip. (For image sources, click on images)

Brussels is the second most multinational city in the world, after New York. Bruxellois refer to themselves as zinneke, which translates to “mutt”. But in Brussels the word has a rather positive connotation, celebrating the unity of the city’s abundant different cultures. When you’re there, you can feel the collectivism: people wear their traditional dress, and eat their cultural food, but they embrace each other as equal constituents of a single Belgian demos.

I want to highlight this progressive convergence of various cultures in Brussels because I recently attended a field trip there, thanks to Pagoda Projects and York St John. The aims of the trip included the development of intercultural fluency, leadership skills, and networking – but its main focus was sustainability. Along the way we took a rather deep dive into the components, causes, and effects of climate change, and at the end received our Carbon Literacy certification.

We looked at the human activities that cause climate change, and discussed ways we can reduce our carbon footprint and increase our handprint of influence.

The simultaneous awareness of the climate emergency that the planet is facing, and the experience of a city that hosts a vibrant and cohesive mix of peoples led me to reflect that it would be devastating if life as we know it collapsed as a result of human-induced environmental decline. We, as a global collective, have evolved so far from the days of empire and colonialization.

While work still needs to be done on the equality front, collaboration of communities is on the rise.

Many citizens of the Earth have reached a collective consciousness and imperative to stand as one against the corporate greed that damages countless lives, destroys fragile ecosystems, emits excessive amounts of greenhouse gases, and diminishes happiness en masse. This diminished happiness permeates the entire supply chain, from miners and farmers through factory workers and those in customer facing roles to the consumers themselves.

Workplace culture driven by strenuous KPI’s and profit targets are largely to blame for employee maltreatment and their resultant unhappiness. The term ‘resource management’ itself implies that companies see people and resources – expedients – to be used for the achievement of their objectives. So for a fairer and more equitable world, entrepreneurs need to reshape their approach to wealth creation and revalue people’s multifaceted ideas, beliefs, talents, and emotions. Constantly treating people as mere resources is unsustainable for employee wellbeing – physically and mentally.

On the customers’ side of the equation, overconsumption – as encouraged by businesses to the point where it’s now a cultural paradigm – is partly to blame for the measured decline in US happiness, as demonstrated in this video. The video (albeit slightly outdated with its chunky old iPod) interrogates the socially and environmentally unsustainable business practices within the current linear economic model; a model which results in enormous amounts of waste dumped in landfill which emits CO2. But that’s only the happiness of a developed country. In yet more ruinous ways, corporations invade underdeveloped countries, annihilate their ecosystems, exploit their people, and ‘externalize costs’ so that those people pay for others’ cheap products with their health and their lives.

Physically toxic work environments are exported to the poorest communities – where even children work – implying that the ones who buy the resultant products can maintain their health and their ignorance.

In this way, the video highlights the overlap between human rights and environmental sustainability. Human rights are violated throughout the supply chain, and as advocates for a sustainable planet, we should also push for the safety and wellbeing of people everywhere. Climate change itself is a manifestation of inequality: the countries which historically contributed and currently contribute the least to climate change are the ones most at risk from the effects of it. These are usually underdeveloped countries which don’t have the level of infrastructure and healthcare to manage increased illness and displacement caused by unprecedented levels of heat, flooding, fires, storms, and ecological disruption.

Such communities endure survival struggles every day. They don’t deserve the mess that the global North has caused.

You can read about the extent of human rights infractions in which most of the developed world is implicated, in Siddharth Kara’s book Cobalt Red: How the Blood of Congo Powers Our Lives. It exposes the devastating conditions that Congolese people work in to mine cobalt – a mineral used to make lithium-ion rechargeable batteries. These batteries power our laptops, smartphones, and electric vehicles. Many people wouldn’t be able to live the way they do without cobalt, but the mining of it is harrowingly dangerous – and involves children. Our embroilment in these crimes is inescapable because the Democratic Republic of Congo supplies roughly 75% of the world’s cobalt.

But in our fight against such human rights infringements, we can look to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (which you can read about here). They address both social and environmental issues, such as poverty and life on land (ie., ecosystems). After all, poverty and hunger are as unsustainable as our current treatment of the planet. These SDGs are the new metrics against which we measure companies’ commitments to human welfare and environmental protection. By considering which SDGs businesses meet – alongside their Environmental, Social, and Governance policies – we now look more closely at the companies’ operations than we did when we examined businesses through the outdated Corporate Social Responsibility framework. A company might have invested in charitable work while continuing to infract human rights and wreck the planet with their procedures.

As a global society, we’re a long way from seeing these goals met. Yet we can all work towards them in some way.

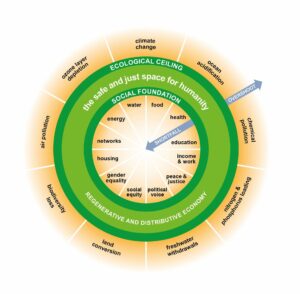

Consumers, now more than ever, demand more transparency about companies’ operations throughout their supply chains, so that we can assess their SDG and ESG commitments (even if we hadn’t come across these specific terms before). Further still, Kate Raworth created an economic model which accounts for both people and planet, giving us a theory to advocate when we push for a fairer and safer society. It’s called doughnut economics. If you picture a doughnut, with its inner and outer edges, you can see a hole in the middle. In that hole resides people who succumb to social inequities such as poverty, poor housing, and gender inequality. An aim of this model is to move people from the hole, into the doughnut – the space in which people can live comfortably. That inner edge points to the social foundations that make up a healthy, happy, and thriving populous. The outer edge is the ecological ceiling, beyond which the Earth cannot sustain human activities. The way we use the planet’s resources also needs to stay within the doughnut if, quite frankly, we’re going to avoid an irreversible climate catastrophe and survive.

Most countries breach both the inner and outer edges of the doughnut, as you can see in interactive detail here. Yet, the Sustainable Global Experience in Brussels showed me the ways in which the European Union is implementing multinational changes to reduce greenhouse gas emissions across Europe. In fact, climate change is the EU’s top priority right now. Policymakers work closely with the European Environmental Bureau, who analyse and edit policies to ensure that they’re the most effective and environmentally sustainable strategies they can be. They even consider various ecosystems’ fragility when looking at proposals to build infrastructure that can produce, store, and distribute renewable energy. Some areas of land can’t handle the development of solar farms for instance, so the EEB step in to protect those areas and suggest alternative options for introducing renewables.

The EEB’s work, the priorities of the EU, and the doughnut theory are all things I learned in Brussels, from passionate and insightful people. In the greenest city in Europe – not only for its dozens of physical green spaces, but also its widespread circular economy – I encountered a group of people from a plethora of backgrounds who share a vision of a fairer and ecologically healthier world. From the Pagoda team members, through the other students from around North England, to the various experts who spoke to us, it was an incredible feeling to find that I’m a part of such a diverse group that is marching together towards humanitarian and planetary progress.

The community that cares about Earth’s people and climate has a culture of its own. It’s warm and welcoming, yet fiery and fervent. It’s gentle towards Earth’s tender spots, but assertive in its resistance against the structures most responsible for social and ecological devastation. But this climate-enthusiast culture which moves as a single unit doesn’t ignore the many glorious cultures that comprise it – it embraces all. In significant ways, it highlights the multitudinous textures within this conglomerate of peoples who share a yearning to protect this planet, and who want to ensure the continuance of vibrancy, positive difference, and communion that human beings can contribute to this planet.

Pagoda ensured that this community became my community – and the most delicious part of it is that it’s a global one. The Sustainable Global Experience gave me the confidence to say and believe that I am indeed a citizen of the Earth. It showed me, in new ways, how life is something that everybody partakes in together, that the future of the planet and the health of its people are things we are all responsible for. This idea that we all share life and the Earth echoes a Nguni term that my hometown in South Africa embodied: ubuntu – I am because we are.